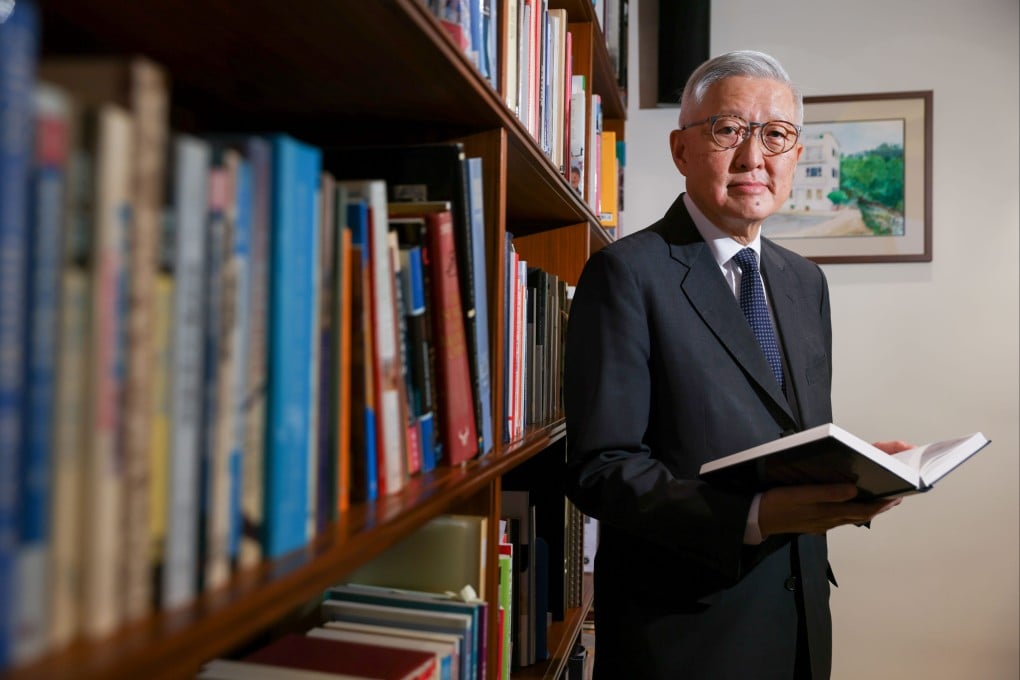

Exclusive interview: Hong Kong’s first chief justice Andrew Li on whether all judges in city should be Chinese nationals ahead of 2047

- City needs to be prepared should fewer non-permanent, overseas judges be available to serve in next 10 years, he says

- Li also calls on younger people to think beyond just their rights, arguing they should also focus on their responsibilities to the community and country

Hong Kong’s first chief justice after the end of British rule expects the question of whether all judges should be Chinese citizens to emerge as among the issues to be debated in the run-up to 2047.

Such matters would surface well before that year, Andrew Li Kwok-nang said, referring to the 50 year mark of the city’s handover of sovereignty from Britain to China amid a promise that its way of life would be preserved under the “one country, two systems” governing model.

In an exclusive interview with the Post to mark the 25th anniversary of the return to Chinese rule, Andrew Li Kwok-nang, who presided over the judiciary from 1997 to 2010, said the rule of law and judicial independence had been maintained in the past quarter century.

“I hope the one country, two systems can continue. I am cautiously optimistic that it will continue in the coming 25 years and hopefully beyond 2047,” he said.

But the city’s former top judge said the future of one country, two systems would have to be settled 10 to 15 years ahead of 2047.

Li, 73, said that despite assurances from senior Beijing officials that the one country, two systems principle would not change after 2047, “sooner or later” Hongkongers would demand “something more concrete” about arrangements for after that date.

Hong Kong is in the midst of preparing for the silver jubilee of the handover, the halfway mark of Beijing’s pledge to uphold the city’s freedoms for at least 50 years.