Filipino’s cancer ordeal underlines the precarious status of domestic helpers in Hong Kong

- Baby Jane Allas was fired by her employer after being diagnosed with stage-three cervical cancer, denying her access to affordable medical treatment

- Many domestic helpers in the city complain of a lack of privacy in employers’ homes and of inadequate nutrition for the work they do

Single mother Baby Jane Allas left her five children in Palawan, the Philippines in late 2017 to become a domestic worker in Hong Kong.

“It wasn’t difficult,” she says. “Not being able to put them through school was harder.”

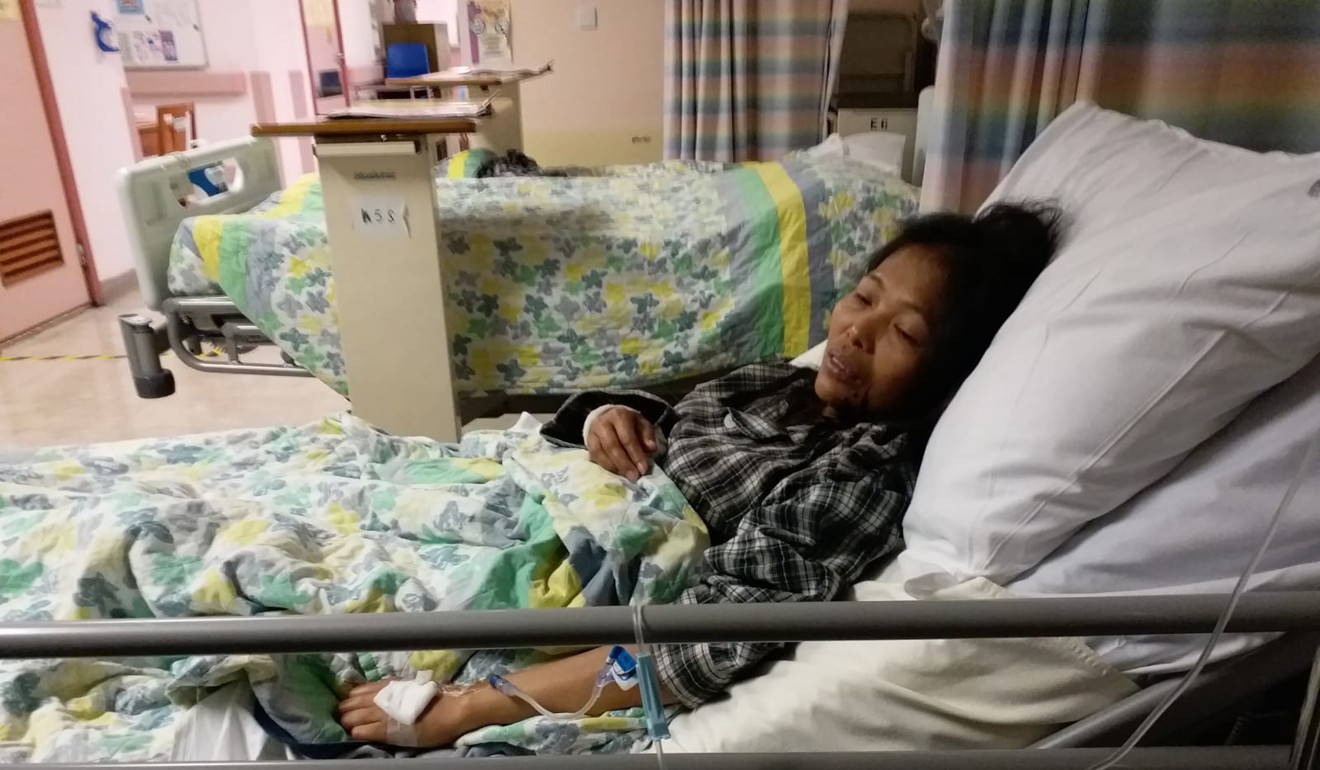

Today, 38-year-old Allas faces another hurdle: stage-three cervical cancer.

Allas’ employer handed her the termination letter while she was on paid medical leave on February 17, but post-dated it to February 19, when she was expected to resume work. Employers who dismiss their helpers during paid sick leave face a fine of up to HK$100,000 if convicted. Allas did not sign the letter.

Late last month, she filed a complaint against her employer at the Labour Department for handing her the dismissal letter while she was on sick leave and claimed her employer committed other violations, such as not giving her one full day off each week.

Allas’ employer had earlier told the Post the helper did not mention she was on sick leave when the termination letter was handed to her, adding that the letter was effective from the date after Allas’ medical leave was finished. The employer did not respond to multiple requests for further comment via telephone, voicemail and text messages before this article was published.

The case has been referred to the Labour Tribunal, where Allas filed her complaint on Monday. Her first hearing at the tribunal will be on April 15.

Since her dismissal, Allas has been receiving medical treatment in the care of her younger sister Mary Ann’s employer, asset manager Jessica Cutrera.

Cutrera, a mother of two, helped Allas raise more than HK$890,000 for her medical expenses through crowdfunding.

“Mary Ann is an important part of our family. She allows me to have the career I have. She supports my home and cares for my children,” Cutrera says of her decision to help the Allas sisters.

Allas’s story highlights the plight of many migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong.

Some 385,000 migrant domestic workers work in the city. About half are from the Philippines, and the rest are from Indonesia and other countries including Thailand. Given the ageing population, the government expects this number to reach 460,000 within a decade.

We Are Like Air: life as a Filipino domestic worker in Hong Kong

Many helpers in Hong Kong complain about a lack of privacy in their employers’ homes, as well as inadequate rest and food. These problems are made worse by the lack of fixed working hours and the city’s rule that helpers must live with their employers.

Advocates believe putting an end to the live-in rule and introducing better regulation of financial institutions and financial education would help.

“Domestic workers come to Hong Kong for financial reasons,” says Zamira Monteiro, a communications officer at Enrich, a charity that promotes the economic empowerment of migrant domestic workers. “If they’re not getting as much out of their jobs as they should be, we need to change things to make sure this is a mutually beneficial arrangement.”

Baby Jane Allas says her challenges began well before her cancer diagnosis.

For more than a year, she slept in a cluttered storage area under the stairs of her employer’s three-bedroom house in Yuen Long. The household comprised four other adults – her employer’s elderly parents, brother and sister-in-law. Allas’ employer and her husband stayed in their home country of Pakistan during most of Allas’ time working for them, only returning to Hong Kong in February.

At 11.30pm each day, after walking the family dog, Allas would move old appliances and food supplies out of the storage area to make space to lie down.

“I couldn’t sleep properly because my employer’s family would still be watching TV, often until 1am,” she says. “But I would still have to get up at 6am the next day to do my chores.”

During her last month there, she was allowed to sleep in an unoccupied bedroom. Allas says she was not sure why. Although there was a bed, Allas was told to sleep on the floor.

According to the government, employers should provide domestic workers with “suitable accommodation with reasonable privacy”.

The long working hours under stressful conditions and the lack of uninterrupted rest impacts the health and well-being of domestic workers

But helpers are often told to sleep on sofas and in hallways, says Edwina Antonio-Santoyo, executive director of Bethune House, a centre which helps domestic workers in need of accommodation or care. It helps about 600 helpers every year, including those in their 20s and 30s who complain of back pain and numbness in their limbs brought on by poor sleeping and working conditions.

Antonio-Santoyo recalls a woman who said she had to sleep curled up against the water tank of a toilet for eight years.

“Even if they arrive in Hong Kong fit to work, the long working hours under stressful conditions and the lack of uninterrupted rest impacts the health and well-being of domestic workers,” she says.

Like most domestic workers, Allas had a day off every week, but on one condition: she had to be home by 8.20pm to clean up after her employer’s family gatherings.

The minimum monthly wage of HK$4,520 for domestic workers includes free food, and employers are required to pay their helpers a monthly food allowance of HK$1,075 if meals are not provided. However, “free food” does not necessarily mean balanced meals.

Baby Jane Allas was only allowed leftovers.

How thousands of female migrant workers lose their money and their children every year

“Even if there was fresh food left over after their meals, I had to finish older leftovers first,” she says. Her employers kept count of the number of eggs and slices of bread in the house and Allas says this was to make sure she was not eating their food.

“I tried buying my own food, but they’d eat it too. And one time, when I tried to cook fish, my employer stopped me because she thought it smelled bad and didn’t want me to waste gas,” she says.

Sringatin, an Indonesian domestic worker and spokeswoman for the Asian Migrants’ Coordinating Body, claims most helpers survive on instant meals because they are cheap and save time and gas.

“I’ve encountered a helper who lived on instant macaroni and frozen vegetables for two years,” says Sringatin who, like many Indonesians, goes by one name only.

“She asked if she could file a complaint against her employer, but how? In the contract, it just states ‘food’ without going into details.”

Sringatin adds that instant meals are not enough to fuel labour-intensive household chores.

Even before her cancer diagnosis, Baby Jane Allas sometimes thought of leaving her employer.

I’ve encountered a helper who lived on instant macaroni and frozen vegetables for two years

“I felt stressed and weak, but I told myself it’s OK, because I have children to feed,” she says. “If I terminated my contract, I would lose two to three months of income while waiting for a new employer. I was also worried about leaving a bad record.”

Once their contracts are terminated, helpers have only two weeks to find a new employer. After that, they must leave Hong Kong, and wait until a new opportunity comes along, which can take two to three months.

“We’re always on the losing end,” says Dolores Balladares, chairperson of United Filipinos in Hong Kong, a labour rights organisation for Filipino domestic workers. “If we want to find another employer, we’ll have to pay agency fees again, even if we still owe the previous agency money. ”

By law, employment agencies in Hong Kong can charge domestic workers up to 10 per cent of their first monthly wage, or around HK$450.

But a 2016 study by the Progressive Labour Union of Domestic Workers in Hong Kong found that 40 out of 57 interviewees from the Philippines paid local recruitment agencies more than HK$11,000 on average.

Domestic helpers want 11 hours rest and for you to stop treating them like ‘slaves’

While recruitment agencies in the Philippines are not allowed to charge placement fees, 84 per cent of respondents told researchers these agencies charged them on average PHP52,644 (HK$7,835).

Two years ago, the Hong Kong government introduced the Code of Practice for Employment Agencies to ensure recruiters play by the rules. But activists insist the problem of overcharging continues.

Sringatin says it is not uncommon for agencies to charge helpers HK$2,000 a month for four months, or HK$8,000 to HK$10,000 upfront.

Helpers who cannot afford the fees take out loans, often from informal moneylenders, including employers and agencies. Enrich says this is mainly due to the lack of documentation, eligibility, knowledge about financial services or confidence in dealing with financial institutions.

According to Justice Centre Hong Kong, a non-profit human rights organisation, half of all domestic workers in Hong Kong in 2016 borrowed money for recruitment purposes – Filipino workers had debts of HK$16,700 on average, while Indonesian helpers owed an average of HK$15,454.

To protect workers from getting trapped in debt, local charity Enrich wants the government to regulate the “unstructured” financial sector which, their study found, charges interest rates as high as 120 per cent.

Now in her second week of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, Baby Jane Allas remains hopeful, with her sister Mary Ann by her side.

She looks forward to spending time with her children and parents after completing her treatment, and even plans to return to Hong Kong to find work after a short break.

“I pray I’ll get a good employer next time,” Allas says.

Hong Kong domestic helper sues ex-employer for secretly filming her in the shower

Back in the Philippines, Allas’ family knows she is sick, but are unaware of the extent of her cancer.

“I don’t want them to be upset. We want to show them we’re strong,” she says.

Activist Balladares hopes the government will relax visa restrictions to give migrant domestic workers more time to find new jobs after their previous contracts are terminated.

This could empower ill-treated helpers to find better employers.

Antonio-Santoyo of Bethune House says helpers will get the rest and privacy they need if they are allowed to live away from their employers and if their working hours are fixed.

She also urged employers not to terminate their helpers’ contracts when they fall ill, especially with cancer.

“Allow your helper to stay in a shelter like ours if you can’t take care of her, but do not terminate her contract or she’ll lose access to affordable treatment,” she says.

Enrich’s Monteiro says employers should take the initiative to ensure their helpers are financially stable by showing concern for their savings plans, or even accompanying them to set up bank accounts. “Without a loan shark banging on your door, your helper can focus on caring for your family members.”