‘We don’t need a baby, we have a cat’: Hong Kong women say no to having children as experts scratch their heads at ways to reverse trend

- Downward trend of births points to impact on schools, workforce and key sectors of city’s economy

- Other places in crisis are offering ‘baby bonuses’, generous parental leave, allowances for children

Teachers, alumni and parents of current pupils staged emotional appeals, signed petitions and lobbied district councillors and lawmakers hoping to save the schools.

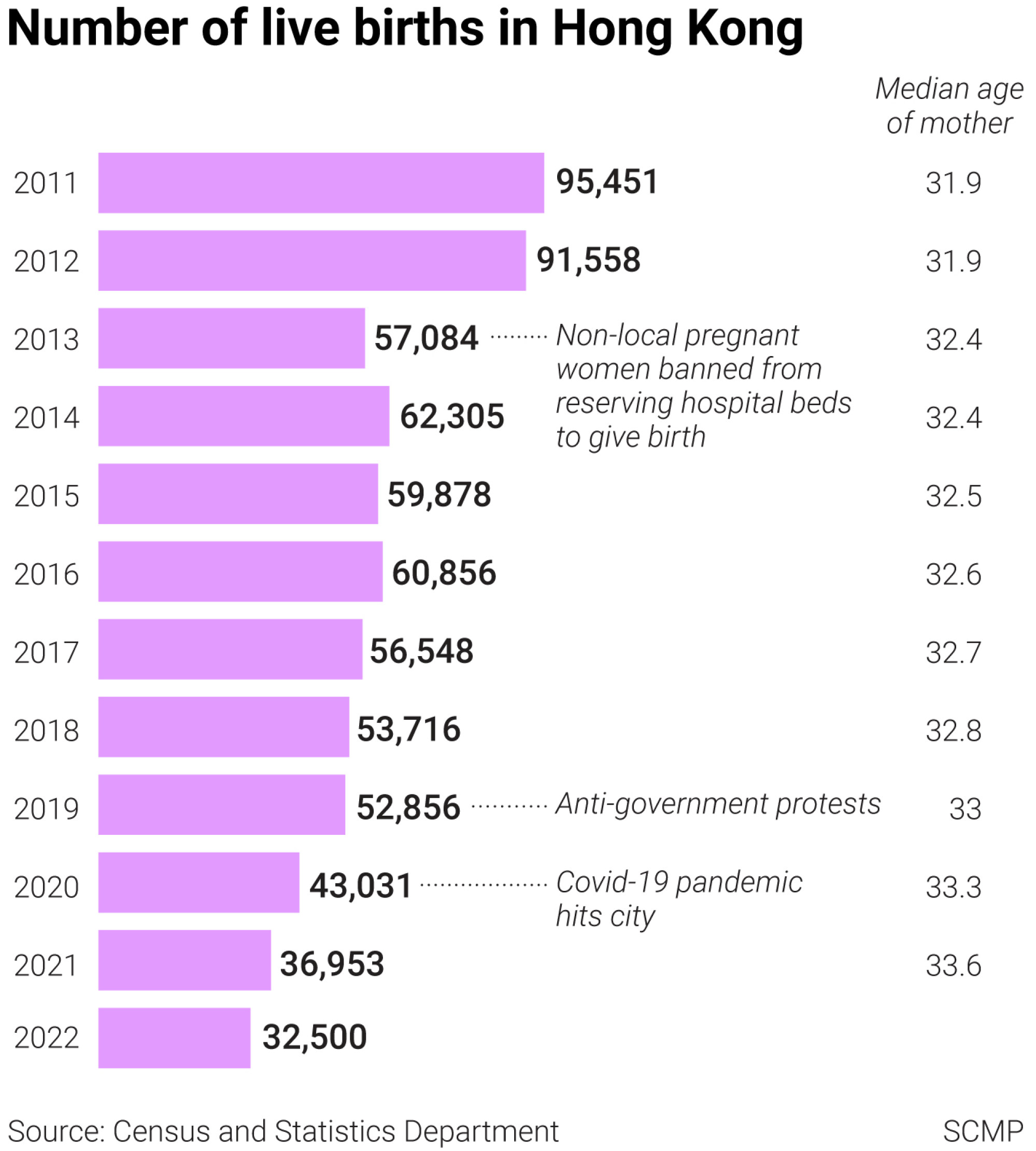

The decision to close them was made because only 56,500 babies were born in 2017 and they start Primary One in September. The city simply has more schools than it needs.

But the number of babies born fell consecutively over the next five years from 2018 to a record low of 32,500 last year, promising worse to come not only for schools, but society itself.

Some preschools and kindergartens have already closed. After primary schools, secondary schools will be hit next, and hundreds of teachers could be made redundant.

“The crisis we face today did not just happen yesterday,” said Paul Yip Siu-fai, chair professor in population health at the University of Hong Kong’s department of social work and administration. “We saw it coming in 2018, but we failed to prepare for it.”

But what has also sunk in over recent years is that younger women and married couples are not only delaying having babies, many do not want them at all.

“The younger generation no longer buys the concept of carrying on the family name,” said Yip, who has tracked Hong Kong’s birth rate for decades.

“They no longer call themselves ‘childless’ but ‘childfree’ and see it in a positive way. That indeed signals more issues ahead.”

‘We don’t need a baby, we have a cat’

A 34-year-old marketing manager who only gave her name as Ah Ying got married three years ago. Her husband was open to having children, but she was not.

She said she dropped the idea completely in the aftermath of the 2019 social unrest, as Beijing tightened its grip through the national security law and the overhaul of the electoral system to ensure that only “patriots” ruled the city.

With schools emphasising patriotism, she feared her children would be “brainwashed”.

But she was also put off by the cost of raising a child and the city’s “competitive” culture which began at the toddler level.

Tax breaks for hiring domestic helpers may boost Hong Kong’s birth rate: study

“Children nowadays are expected to learn many things, take part in a lot of courses and go through rounds of interviews [to get into good schools],” she said.

“It’s not only about the emotional stress, but also the financial burden. If I can’t provide my child with the best, maybe I should not give birth at all.”

She and her husband adopted a cat last year and regard it as a member of the family. They have stopped talking about babies.

The change in attitudes over time is reflected in the data.

More than three in four Hong Kong women born in 1951 had at least one child before they reached 30. For women born in 1991, however, fewer than one in four had a child by 30.

The government said women were having their first child later than before, and more women were remaining childless at the end of the reproduction span.

According to a report by the United Nations Population Fund last month, Hong Kong also fared worst for its total fertility rate or TFR – the number of children a woman is expected to have over her lifetime.

Hong Kong’s score of 0.8 was the lowest in the world, followed by South Korea at 0.9, Singapore at 1.0 and Japan at 1.3. The TFR should be 2.1 for a population to replace itself.

Among developed Western countries, France had a TFR of 1.8, followed by 1.7 in the United States and 1.6 in Britain.

The shortage of babies has spurred several places into action to reverse the birth trends, with Scandinavian countries taking the lead with generous benefits for parents.

In Sweden, with a TFR of 1.7, both parents receive a combined 480 days of parental benefits per child, referring to the money one gets to be able to stay home with the children instead of working, looking for work or studying.

Tax incentives ‘not enough’ to reverse Hong Kong’s declining birth rate

Parents in Denmark, which also has a TFR of 1.7, get 52 weeks of paid parental leave.

Earlier this year, Japan seized what it said was possibly “a last chance” to reverse its declining birth rate by introducing a raft of unprecedented measures, boosting government subsidies for child rearing, strengthening access to childcare services and changing the cultural mindset by encouraging more fathers to take paternity leave.

Currently, every child in a poor family gets a monthly childcare allowance of ¥15,000 (US$110) until the age of three. After that, a ¥10,000 allowance is provided until the child graduates from junior high school.

Tokyo plans to scrap the income threshold for the allowance and extend it until the child graduates from high school. The lump sum childbirth allowance paid to all mothers will rise from ¥420,000 to ¥500,000.

South Korea and Singapore have long tried to reverse their falling birth rates with cash incentives, with little success so far.

South Korea is boosting its incentives. Korean mothers currently receive 2 million won (US$1,495) upon the birth of a child.

Babies receive a monthly allowance of 700,000 won in their first year, and then 350,000 won a month until age two. The allowance will rise to 1 million won and 500,000 won respectively next year, with a monthly allowance of 200,000 won until the children start elementary school.

Singapore pays “baby bonuses” of S$11,000 (US$8,224) each for the first and second child, and S$13,000 each for the third and subsequent child, with the payments made in instalments.

The government also puts S$5,000 into a special “child development account” which can be used for educational or healthcare purposes. It also matches deposits by the parents, subject to a cap, until the child turns 12.

Singapore’s fertility rate hits all-time low as births plunge in Year of Tiger

‘Working mums need more daycare centres’

Unlike its Asian neighbours, Hong Kong has resisted offering cash incentives for babies, although the government has extended maternity leave by four weeks to 14 weeks and paternity leave from three days to five, and has a child tax allowance.

Secretary for Labour and Welfare Chris Sun Yuk-han earlier said choosing to have a child was an “important family decision” and the government should avoid excessive intervention in such matters, but foster a supportive environment for parents.

Lawmaker and mother of two Eunice Yung Hoi-yan, whose New People’s Party had called for more progressive measures to boost the birth rate, said: “No one will decide to give birth because of a tax allowance.”

She said the city’s population policy now focused mainly on luring global talent, an approach she described as “short-sighted”.

Yung called for the re-establishment of a high-level committee on population policy similar to the one set up in 2012 – an idea dismissed by the government last month – and a thorough population policy with targeted measures to encourage Hongkongers to have babies.

The first lawmaker to give birth during her tenure, Yung admitted that she spent little time with her two girls, now aged four and three.

“I can only see them and give them a hug during the 15 minutes when they get ready for school every morning. When I return at 9.30pm after dinner appointments, they are already asleep,” she said. “A lot of parents in Hong Kong are facing the same.”

She urged the government to take the lead by introducing a workplace day care in government premises, so that civil servants working there could spend more time with their children.

Professor Terence Chong Tai-leung, executive director of Chinese University’s Lau Chor Tak Institute of Global Economics and Finance, said the government had sufficient financial reserves to provide cash benefits or roll out more family-friendly measures such as extending maternity and paternity leave.

But he was convinced that none of these measures would help to reverse the trend.

“No mature economy in the world has succeeded in lifting its fertility rate because they could never resolve the crux of the issue, the high opportunity cost for women,” he said.

“With more women securing decent jobs after graduating from universities, it is only natural that they do not want to have children.”

About 10 per cent of Hong Kong’s kindergartens at risk of closing: teacher group

Chong warned that there was “no future” for the economy – and the property market – of any place with a shrinking population. The only solution was to import young people.

Indeed, the Post has learned that some lawmakers are planning to put forward a controversial suggestion for the government to lift the ban on non-local women – whose husbands are not Hong Kong residents – reserving hospital beds to have their babies born in the city.

Hong Kong hit a record of 95,500 babies born in 2011 thanks to mainland Chinese women who flocked to give birth in the city so that their children would have the right to live in Hong Kong.

Responding to the outcry, the city government banned non-local pregnant women from reserving hospital beds to give birth from 2013. The number of babies born dropped sharply that year.

Now some believe it might be time to let non-locals back to have their babies in Hong Kong.

Some school leaders who believe this could help their schools survive have preferred not to say anything openly yet, because of what happened in the past.

Hong Kong preschools hit by shrinking enrolment offered new sites, incentives

Population expert Yip warned that lifting the ban could bring more problems.

“Only children born in Hong Kong enjoy the right of abode here, not their parents. There will be a lot of problems concerning their day-to-day care, not to mention the financial burden,” he said.

“Most of these babies actually would also be brought back to the mainland as their parents only wanted to secure their right of abode in Hong Kong”.

At this late stage of the city’s baby shortage, the authorities should plan to tackle foreseeable challenges, optimise teaching as more schools close, and improve the living conditions of elderly residents, Yip said.

Childless residents also needed to understand that they had a duty to contribute financially towards elderly care, so that they too would be looked after one day, he added.

Yip said Hong Kong had no shortage of women, but what had changed was their motivation to have babies.

“The social environment has to change to make everyone feel there is hope here, and perhaps that can prompt those who left the city to return as well,” he said.