‘A truly remarkable phenomenon’: how a medieval imperial exam helped dismantle the aristocracy in Tang-era China

- New paper reveals medieval exam laid foundations of meritocracy in China

- Scientists prove that passing test drove dismantling of Tang-era aristocracy

Education is valued today because it is viewed as an avenue for social mobility and a means for people who grew up poor to improve their lot in life and find opportunities to support themselves and their families.

But this phenomenon is not a feature of modernity.

During China’s Tang dynasty, (618–907), one specific test, called the keju, created the means for people to circumnavigate the entrenched aristocracy and begin a career in the bureaucracy, according to a new paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, a peer-reviewed journal.

“Our paper shows that even in a decidedly pre-modern society like medieval China, some institutional transformation like keju could activate the link between education and political success,” said Erik Wang, an assistant professor of politics at New York University and author of the study.

The best modern comparison to the keju would be the guokao civil service exams, in which more than three million people sat in 2023, competing for 40,000 government jobs.

While more data is needed to analyse the participation rate in the keju, only around 100 people passed the exam in a given year, and just 30 of them received the highest degree.

The study showed that the correlation between those who passed the test, and those born into high-ranking families, decreased through the Tang dynasty, suggesting that the keju became a powerful tool to break down the aristocracy.

“Before the Tang dynasty, there were people who were quite educated but were not from prominent aristocratic families. The chance for them to get jobs in the bureaucracy was quite limited. What the keju did was to enable educated elites to enter the bureaucracy,” said Wang.

Prior to the keju, the likely path for these educated civilians would have been to work as a clerk doing paperwork for officials, or educating those aristocrats destined for politics.

Fangqi Wen, an assistant professor at Ohio State University, and also an author of the study, said a key turning point for the keju was the reforms initiated by Empress Wu Zetian (r. 690-705), the first and only empress of China, in which she lowered the barrier to entry for those who could take the test.

“Most adult men who could read and write were qualified to take the exams, so the Empress’s reforms also likely increased the fairness of the competition,” said Wen. “This was important because success in the keju is more deterministic of future success than college entrance exams today.”

“Among men who could read and write, after the Empress’s reforms, most of them were qualified to take the exams,” she said, adding that passing the keju was more deterministic in terms of favourable future outcomes, said Wen.

She also said that, as time passed, there was some multi-generational improvement of status, but it no longer became guaranteed that a grandfather’s success would lead to a career for the grandchild because the individual still had to pass the exam.

“Success was no longer guaranteed, so no family was able to monopolise the government post,” she said. “It became very normal that the son or grandson of a high-ranked official would fail the exam.”

Wang added that it was not unheard of for the ancestors of chief ministers – the highest position – to be entirely out of the bureaucracy within a few generations.

The team found that as the keju grew in social prominence and more people took the test, it did not correlate with a drop in its impact.

“We’ve seen in history that when a degree expands, the value of the degree dilutes. But the keju in the Tang dynasty was a truly remarkable phenomenon because of the continued rise in its social impact despite the fact that, after Empress Wu, more people received the degree,” said Wang.

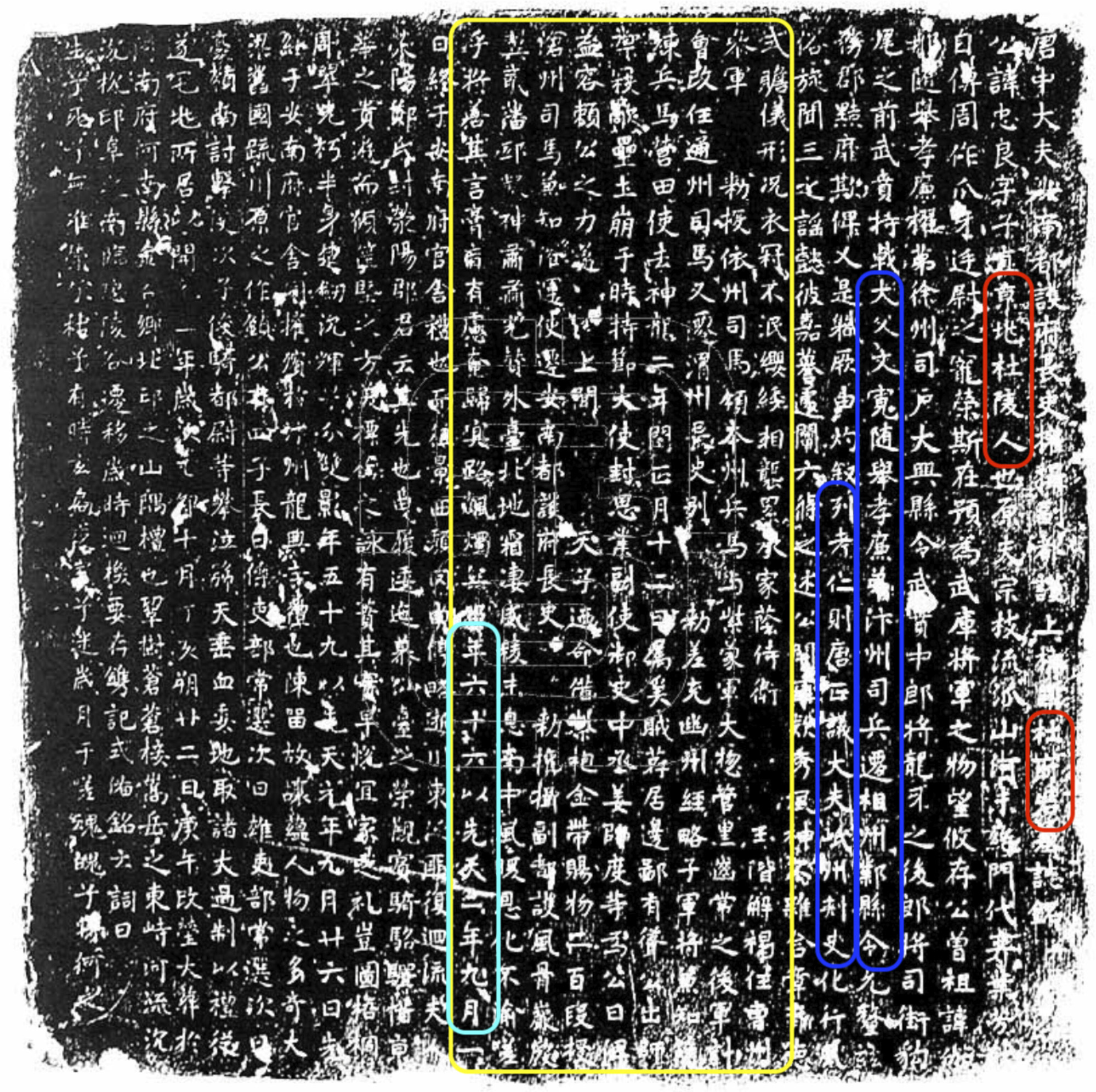

The team’s data-gathering process was impressive, with the analysts scouring through Tang-era epitaphs, or short remembrances of a deceased person, to see if the person passed the exam.

They cross-referenced that information with databases from towns that marked who in their villages passed the keju.

They then investigated the individual’s office rank and compared it with the highest offices their father or grandfather reached, allowing them to see if they climbed the social ladder.

Finally, for each epitaph, they painstakingly identified whether the person could be credibly traced to an aristocratic family branch.

After filtering all of this information through a regression model, the team found that there was a correlation between passing the keju and career success.

For Wen, the key takeaway of this data analysis was in proving that social mobility was not a modern phenomenon.

“Usually social scientists will link social mobility with industrialisation and modernity, so social mobility has been considered a modern phenomenon… and competitive exams, even in medieval times, can also improve social mobility,” she said.