British workers are striking as UK rights come under scrutiny

- Britain has been hit by strikes that have impacted essential services, including health and transport

- UK government eyeing laws that could place new restrictions on the right to peaceful protest

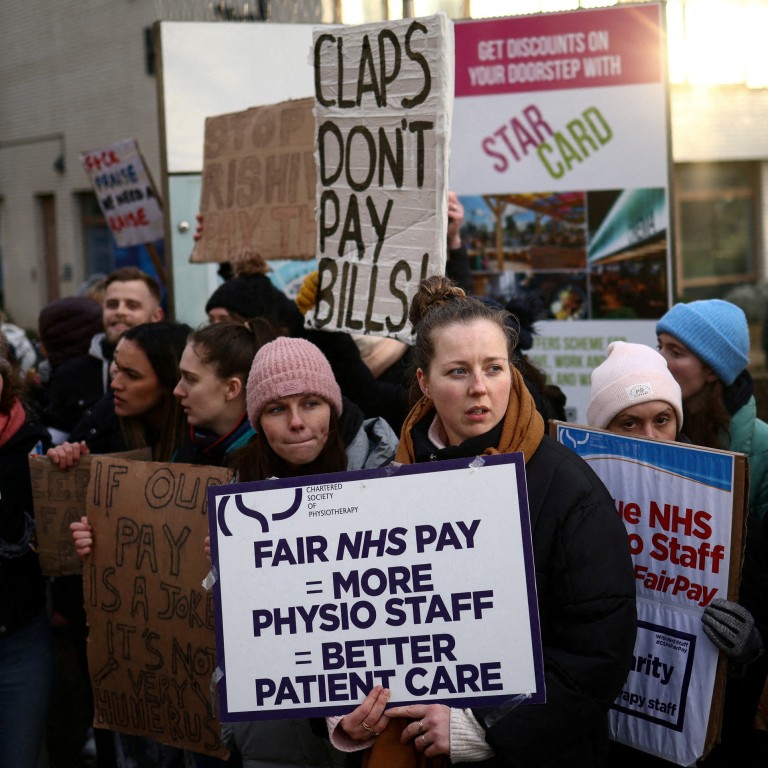

Half a million people could join one of Britain’s biggest strikes in decades next week, as the UK government pushes for new laws that could mean dismissal for essential workers who join in industrial action.

Britain has in recent months been hit by waves of strikes that have shut down or significantly reduced public services, including health and transport.

The next nationwide strike over pay, planned for Wednesday, comes as millions in the UK bear the brunt of the cost of living crisis and double-digit inflation, with nurses among workers resorting to food banks.

This is happening while there is a perceived deterioration of basic civil liberties in the UK. Rights groups say the UK’s Conservative government has curtailed human rights on issues ranging from peaceful protest to an adequate standard of living.

Positions have hardened on both sides with unions claiming the government has not wanted to discuss pay increases.

The government says pay rises would fuel inflation. But unions say more than a decade of cuts has led to depleted services, chronic staff shortages especially in the health sector.

As many in the UK struggle, is Rishi Sunak’s wealth a liability or asset?

Workers including teachers, university staff, train drivers, Border Force personnel and other civil service workers plan to strike on February 1.

Recent strike chaos has drawn some comparisons to the “Winter of Discontent” in late 1978 early 1979 when a wave of strikes brought Britain to a virtual standstill.

The government of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, the richest person in the House of Commons and Britain’s third leader in less than a year, is pushing for new laws that could make workers reconsider walkout action.

The proposed Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Bill 2022-23 would allow one minister, the business secretary, to determine “minimum services levels” of essential staff to limit disruption to the public during strikes.

It would impact a range of roles in essential sectors, from public hospital nurses to the fire brigade, who could face possible dismissal if they don’t work as ordered.

The bill passed its second reading in the House of Commons last week. It moves to the House of Lords where it faces opposition, even from some Conservative peers.

Some critics have called the bill anti-union and an attack on democracy, designed to conscript workers to work against their will.

“If they were doing that in [Vladimir] Putin’s Russia, or in Iran, or China, they would rightly be condemned,” Mick Lynch, the leader of the railway workers union RMT said this month.

The government’s proposals are also attracting attention abroad.

US Labour Secretary Marty Walsh told the BBC he disagreed with the idea of “minimum service” agreements for public sector workers as they may be detrimental to workers.

How living in London is becoming increasingly unaffordable

The main EU trade union bodies have written to the European Parliament asking it to ensure the “protection of the right of association and right to strike” in any post-Brexit trade agreements with the UK.

They have also repudiated Sunak’s claim that France, Italy and Spain had similar deals in place.

“The context for industrial action in these countries is very different and so it is certainly wholly inaccurate for the government to claim it is bringing a UK strike law into line with the situation in these countries,” Jan Willem Goudriaan, general secretary of the European Federation of Public Services Trade Unions told South China Morning Post.

“All three of these countries guarantee the right to strike in their constitutions in contrast to just the immunity provided to striking workers in the UK.”

In the UK there is no legislation that gives British workers the right to strike, only laws protecting them from legal action from employers if they do. UK unions have to ballot their members by post before taking industrial action.

The proposed Strikes Bill joins the Public Order Bill, another piece of legislation before parliament. The second bill gives police a raft of extra powers to deal with disruptive protesters in England and Wales.

Once law, police would be given the authority to stop and search anyone they suspect of intending to take part in a disruptive protest, and to lock down entire areas should one occur.

Opposition Labour leader Keir Starmer, a former head of public prosecutions, said police already had powers to prevent disruptive protests.

Britain to get tough on disruptive protests, activists fear new powers

Britain’s government insists it is not anti-protest. But its proposed enhanced measures against disruptive protests and strikes stands in contrast to its critical position of Beijing’s policies on Hong Kong, and the Hong Kong government’s response to the social unrest of 2019.

This week, 20 of Britain’s minority religious leaders wrote to Sunak expressing their concern about the Public Order Bill, the Church Times reported.

“New stop and search powers, which can be exercised without the need for reasonable suspicion, would exacerbate the unacceptable levels of discrimination that already result from existing powers,” they wrote.

Even the British cosmetics chain The Body Shop weighed in.

In 2022, we saw the most significant assault on human rights protections in the UK in decades

“In its current form, the [Public Order Bill] goes far beyond addressing the criminal activity of a few – it will change the very fabric of our society by discouraging people from exercising their democratic rights,” said Chris Davis, The Body Shop’s international director of activism and sustainability.

“Without action, the voices of Britain could be silenced. People will feel scared and intimidated into thinking that simply attending a peaceful protest could put them on the wrong side of the law.”

Meanwhile, the UK parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights has called on the government to abandon its proposed British Bill of Rights, which would replace the Human Rights Act of 1998.

The Human Rights Act makes the rights contained in the European Convention on Human Rights enforceable in the UK.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) said that if the British Bill of Rights is adopted it would “fundamentally undermine human rights protections in the UK”.

“In 2022, we saw the most significant assault on human rights protections in the UK in decades,” said Yasmine Ahmed, UK director at HRW.

Amnesty International also expressed concern.

“The government’s increasingly negative approach to human rights in the UK is worrying and deeply damaging to our international reputation, which will make it harder to hold repressive regimes to account,” Amnesty International UK’s chief executive Sacha Deshmukh said in a statement.