US bill aiming to delist Chinese companies could claim American investors, businesses as unintended victims

- If Chinese firms continue their exit from US exchanges, funds will lose easy access to shares of companies in the world’s second-largest economy

- The Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act would require foreign companies to submit audits for inspection, which Beijing has long refused to do

Sweeping legislation that could remove publicly traded Chinese companies from US stock exchanges has the potential to trip up businesses and investors at home as Chinese firms move to other countries for capital.

Policy watchers and investors, however, said domestic businesses and investment funds could become unintended victims if Chinese companies begin to leave the US as a result.

“While it is going to hurt China, is it going to hurt it enough for the government to agree to the changes? That is unclear,” said Anna Ashton, senior director of government affairs at the US-China Business Council. It is yet “another instance among many [that] our approach against China wasn’t completely thought through”.

07:16

Hong Kong stocks will be 'fairly volatile' amid coronavirus, US-China tensions, says analyst

If Chinese companies start leaving US exchanges, shareholders would suffer as evaporating trading volume would drag down stocks’ value.

China’s biggest chip maker to delist from NYSE as US targets tech

Disowning Chinese stocks is not an option.

“In the current market, with tech outperforming, it’s almost impossible for fund managers to match or outperform the MSCI China [Index] if they do not own companies like Alibaba, and to a lesser extent Baidu, NetEase and JD,” said Rory Green, China Economist at TS Lombard, a New York-based research firm.

Allocation to Chinese American Depositary Receipts (ADR) among active emerging markets funds increased 10 points from a year ago to 35 per cent in April, according to Morningstar.

But the changes would mean “scrambling and hustling” to maintain similar exposure to these companies as listings are removed or moved to different exchanges, said David Semple, a portfolio manager at US$1.9 billion VanEck EM Equity Strategy funds in New York.

Semple had 41 per cent of his funds’ portfolio in Chinese companies – including Alibaba and Tencent – as of May 31. China has been the single largest country of exposure in his investments, and he continues to consider it a “must-have”.

Even though large funds could invest in the same stocks listed in Hong Kong, only three – Alibaba, JD.com and NetEase – are dual listed in New York and Hong Kong. All three Hong Kong secondary listings took place recently, indicating a change in thinking among Chinese companies that have traditionally preferred New York exchanges for prestige and liquidity.

Alibaba, the New York Stock Exchange-listed e-commerce giant and owner of the South China Morning Post, sold US$13 billion of shares in Hong Kong in November. The move was a big win after the city lost the highly coveted US$25 billion IPO to the US six years ago.

Following suit was JD.com. Last week, when JD planned to sell US$4.1 billion worth of shares in Hong Kong, institutional demand was so strong that subscriptions exceeded that amount by multiple times.

Pompeo warns US investors against ‘fraudulent Chinese companies’

And Baidu, China’s search-engine giant, was reportedly considering delisting from Nasdaq. A company representative denied the delisting reports in an email on Monday, saying they were rumours.

For large Chinese companies, delisting from US exchanges would mean “one set of investors is effectively being replaced by another set of investors,” said Semple. “And that other set of investors is very familiar with those companies.”

The impact “could actually be positive” for large companies, said Green, because “relisting in Hong Kong might see their shares trade at a premium to US valuations”.

05:20

Alibaba makes a solid debut on Hong Kong stock exchange, says analyst Kenny Wen

The valuation gap exists because Hong Kong shares offer a direct ownership in Chinese companies, while the US ADRs have an indirect claim through a so-called viable interest entity (VIE) providing a contractual right to companies’ profit.

“My worry is that [the bill] is going to have a chilling effect on Chinese companies going public in the US,” said Bill Ford, chief executive at private equity giant General Atlantic, which manages US$34 billion in assets.

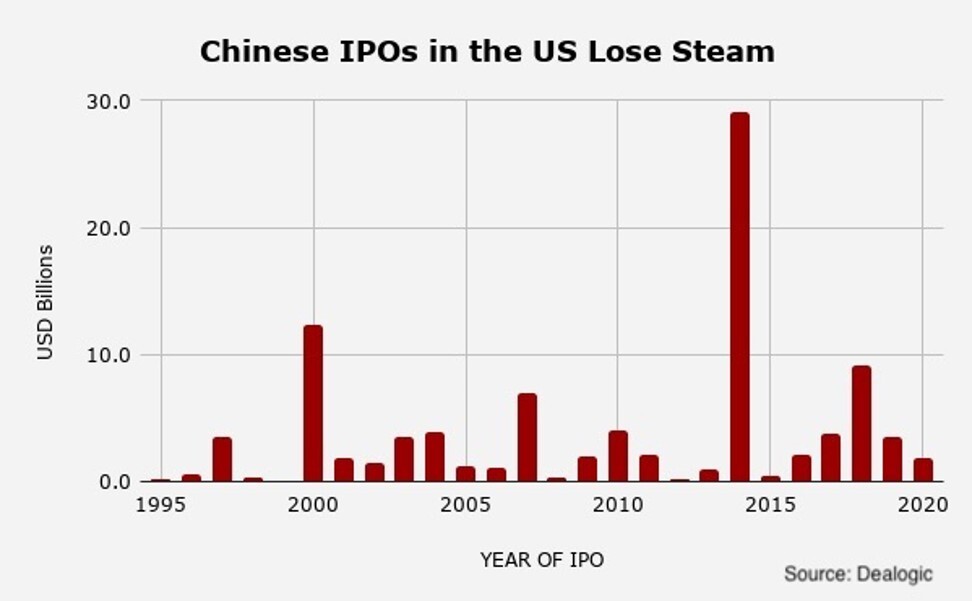

The demand by Chinese companies to raise US capital has already eased significantly because of the pandemic and the less-than-welcoming attitude from Washington. The group has raised only US$1.9 billion in US public offerings this year, the lowest since 2015, Dealogic data shows.

These companies “have a very viable alternative – Hong Kong.” It may not be “as deep as New York, but it's pretty deep” and “very well regulated”, said Ford at a discussion hosted by the National Committee on US-China Relations this month.

Hong Kong stock exchange, at US$5 trillion at the end of 2019, was much smaller compared to the US$23 trillion New York Stock Exchange and the US$11 trillion Nasdaq.

Adding the exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen, through, the trio rivals Nasdaq at US$12 trillion.

With the threat from the pending legislation, the US is helping make the case for Beijing to lure its companies closer to home, a mission China has tried but failed to accomplish for years.

US-China tensions dampen Chinese tech firms’ US listing plans

If China retaliates, there is “a serious possibility” that American companies with large operations in China “can also be delisted from the US exchanges under the same law” if Beijing refuses to hand over US firms’ audits of financials in China, said Ashton.

There is “a cost to this legislation for US investors and markets”, said Semple, who then referred to the US Securities and Exchange Commission. “That’s why the SEC was so unwilling to put down the hammer on that.”

The SEC has been locked in a decades-long struggle with China, one of the few countries refused to comply with listing rules, citing state secret laws. In 2002, a US federal law established the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to inspect accounting firms’ audits of foreign public companies.

All the rest of us want is for China to play by the rules

The problem with China worsened when more than 50 companies, including Universal Travel and China Century Dragon Media, were removed from New York exchanges for accounting fraud in 2011.

Since then, little progress has been made in changing China’s behaviour, partly because the SEC and the US stock exchanges do not want to lose the hefty fees the industry receives from listing the companies.

In 2018, US regulator said that it faced “obstacles in inspecting the principal auditors’ work” on 224 listed companies. Of those, 213 were Chinese.

In April, Luckin Coffee became the latest crash. Less than a year after the Chinese rival to Starbucks went public on the Nasdaq, an employee was found to have fabricated as much as US$310 million in sales. Its ADRs sank to US$2 apiece from their US$50 peak, wiping out US$11.5 billion in investor money.

“All the rest of us want is for China to play by the rules,” Senator John Kennedy, the Louisiana Republican who wrote the pending legislation, said last month.

In response, the Chinese securities regulator said in a statement in May it opposed the US’ practice of politicising securities regulations, saying certain provisions in the bill are directed at China rather than based on professional consideration of security laws.

“The bill ignored completely the fact that regulators of China and the US have been working hard to improve audit inspection,” said China Securities Regulatory Commission.

For example, “China assisted PCAOB on an investigation of a Chinese accounting firm in 2017. China has also in multiple occasions suggested detailed plans to PCAOB on how to jointly inspect audits since 2019. We hope US regulators could respond to these suggestions.”

Now, tensions between the two countries over trade and technology have pushed the drawn-out issue to a head. While House passage of the bill is uncertain, there is broad and bipartisan support.

Luckin’s founder apologises as Nasdaq prepares to delist his stock

Right now, “there is no countering voice among either Republicans or Democrats,” said Ford. “The receptivity on this issue is that people on both sides have the same reaction, and that is the negative reaction.”

SEC Chairman Jay Clayton said in April that there was a “substantially greater risk” for US investors to buy Chinese stocks where “disclosures will be incomplete or misleading and, in the event of investor harm, substantially less access to recourse, in comparison to US domestic companies”.

The push for changes from China may be justified, but many fear they could leave US markets less robust and with less profit for investors.

Beijing, meanwhile, is making it easier for Chinese companies to access domestic capital and be less reliant on other sources. Last week, it finalised new rules on Shenzhen’s ChiNext board to encourage listings from tech start-ups.

In the last year, two firms, Huatai Securities and China Pacific Insurance, have listed on the London Stock Exchange through Shanghai-London Stock Connect, a scheme that allows companies on either market to list and trade with the other.

As in many other cases, to address the problem with China, “a multilateral approach will be better than a unilateral approach”, said Ashton of the US-China Business Council.

And for Chinese companies, handing over audits seems unlikely. “The choice for them is between staying in compliance with PCAOB and violating Chinese state secret law,” Ashton said. “That’s not a difficult choice to make.”