Macroscope | A strong US dollar could bring Asia more pain, especially if Trump wins

- The prospect of ‘higher for longer’ interest rates and a ‘stronger for longer’ US dollar has hit Asian markets particularly hard, with Japan an extreme example

- The only way the dollar will fall meaningfully is if the US economy slows sharply and the Fed cuts rates sooner and at a faster pace than markets expect

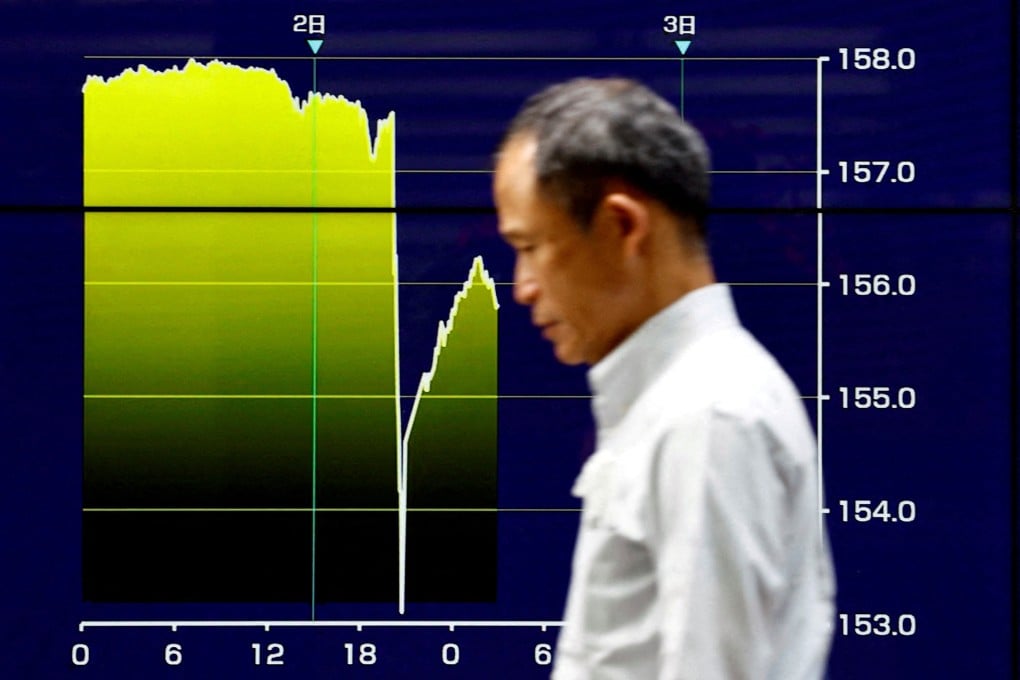

Having strengthened 3.3 per cent versus the US dollar last week, the yen has resumed its decline, sliding back towards the 160 per dollar level that triggered the suspected intervention. It is down more than 10 per cent against the dollar this year, taking its losses during the past three years to a staggering 43 per cent.

The prospect of “higher for longer” interest rates and a “stronger for longer” US dollar has hit Asian markets particularly hard. The yen is the most extreme example of a region-wide vulnerability. With the exception of India, interest rates in Asia’s main economies are significantly lower than in the US, unlike in Latin America and Eastern Europe, where borrowing costs in the leading markets remain higher despite the start of monetary easing cycles.