Instead of labels like ESG, let’s prioritise good old integrity

- It can be hard to evaluate a company’s environmental, social and corporate governance performance amid the profusion of standards. But there is always integrity, accountability and humility to fall back on

So many acronyms, so little time.

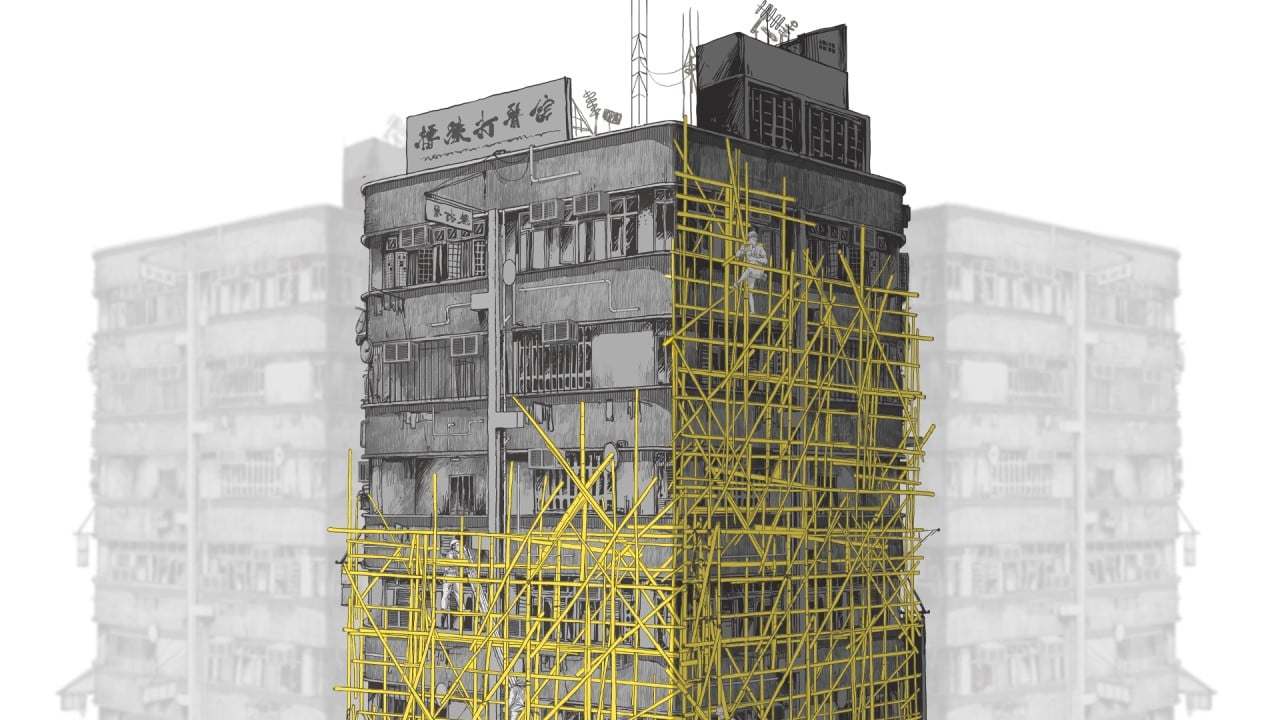

In design and construction, more standards and programmes have surfaced in the evolving call for green and sustainable design. With some catchy acronyms, it can feel like the name was reverse-engineered to fit.

Popular acronyms include LEED, which stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, and BREEAM, for Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method. In Hong Kong, we have abbreviations such as BEAM Plus (Building Environmental Assessment Method Plus).

Most architects, already familiar with green design systems, sustainable materials and products, and the means to reduce the carbon footprint, emissions and wastage in building construction and operation, can readily tackle the “E” of ESG.

The “S” refers to social impact, including on the surrounding neighbourhoods and society at large, and this is highly dependent on outcomes, which take time to realise. The “G” refers to the company’s principles in leadership, management, standards in diversity, inclusivity and the upholding of human rights as well as stakeholders’ interests.

Of course, ESG does not apply merely to the design and construction industry. It can apply to any commercial activity, addressing non-financial risks and opportunities in day-to-day operations: from a company’s internal structure, resource planning, investments and policymaking to its engagement with consultants, suppliers, users, consumers and neighbours.

From the Hong Kong Chartered Governance Institute to property management giant Jones Lang LaSalle to the Diginex online platform, different organisations have come up with their own ESG training courses, ratings and tools. Gensler, one of the world’s biggest architecture firms, is developing a broad ESG analysis tool for companies to evaluate the properties in their portfolio. How is a company to evaluate its ESG performance with any clarity when there are yet to be common standards?

Despite these multifaceted challenges, however, corporations from Schneider Electric and Disney to Starbucks and Apple are paying their executives based on their ESG performance, leading to the new phenomenon of ESG-linked pay. So, it seems, instead of encouraging acts of goodness for the environment and society from the heart, ESG is becoming yet another performance indicator that we have to tick off for a bigger bonus, a better reputation.

‘Loopholes’ endanger Hong Kong’s status as green finance hub: Greenpeace

Instead of looking for labels to earn, we should identify where we have not done enough and find ways to improve the weak links, be accountable for our actions and the damage we have done to the environment or to others, be humble about our limits and capabilities, and seek ways to collaborate and share resources.

Harvard economist and 2016 Nobel Prize laureate in Economic Sciences Oliver Hart reportedly believes that investors can drive changes that improve the world. In a 2022 interview, he said it was not helpful for investors to avoid “dirty” companies altogether.

Instead, investors can “engage with these companies and hold them responsible”. He says, “Using your voting power, and passing shareholder resolutions or electing people to the board who are going to actually change the company – that, I think, is a much more powerful mechanism”. He also suggested that “diversified shareholders might be willing to sacrifice some profit for the greater good”.

What ESG demands from commerce is a cultural shift towards a stronger sense of responsibility, not just to company shareholders, but to third parties who stand to be affected by company actions. Responsibility means a shift from Wall Street character Gordon Gekko’s “greed is good” mentality and economist Milton Friedman’s 1970 doctrine “The Social Responsibility of Business Is To Increase Its Profits”.

If we have such a sense of responsibility in our core values, we do not need fancy acronyms, photo opportunities in front of “green” banners, or certificates and plaques. All we need is good old integrity, accountability and humility in conducting any business, private or public – surely we all know that we live in an interdependent world and our actions affect others.

Dennis Lee is a Hong Kong-born, America-licensed architect with years of design experience in the US and China