Diego Maradona: the boy wonder who became a god for more than just his ‘hand’

- They still sing his name at Argentinos Juniors and outside the stadium street art shows El Diego as a kid, an adult, lifting the World Cup and ‘Hand of God’

- ‘At that age most kids hear stories, he hears ovations,’ wrote one newspaper of a young Maradona announcing himself to Argentina football

The Estadio Diego Armando Maradona lies in the middle-class suburb of La Paternal, 10 kilometres to the east of the centre of Buenos Aires. The capacity is optimistically listed as 26,000 for the three-sided, mostly terraced home of Argentinos Juniors with concrete stands painted in red and white.

It’s a proud football club with a fine track record of developing young players from Juan Roman Riquelme to Cambiasso, Sorin to Placente, Julio Arca and Coloccini. Maradona is by far the most famous of its graduates and his image is everywhere.

“He put Argentinos Juniors on the map,” Arca, who played Premier League football, tells SCMP. “Once he’d been there, everyone knew it as the club where Maradona started and because the club didn’t have money, they needed to find talents. A wave of talented players came through. None of us were anything like as good as him though.”

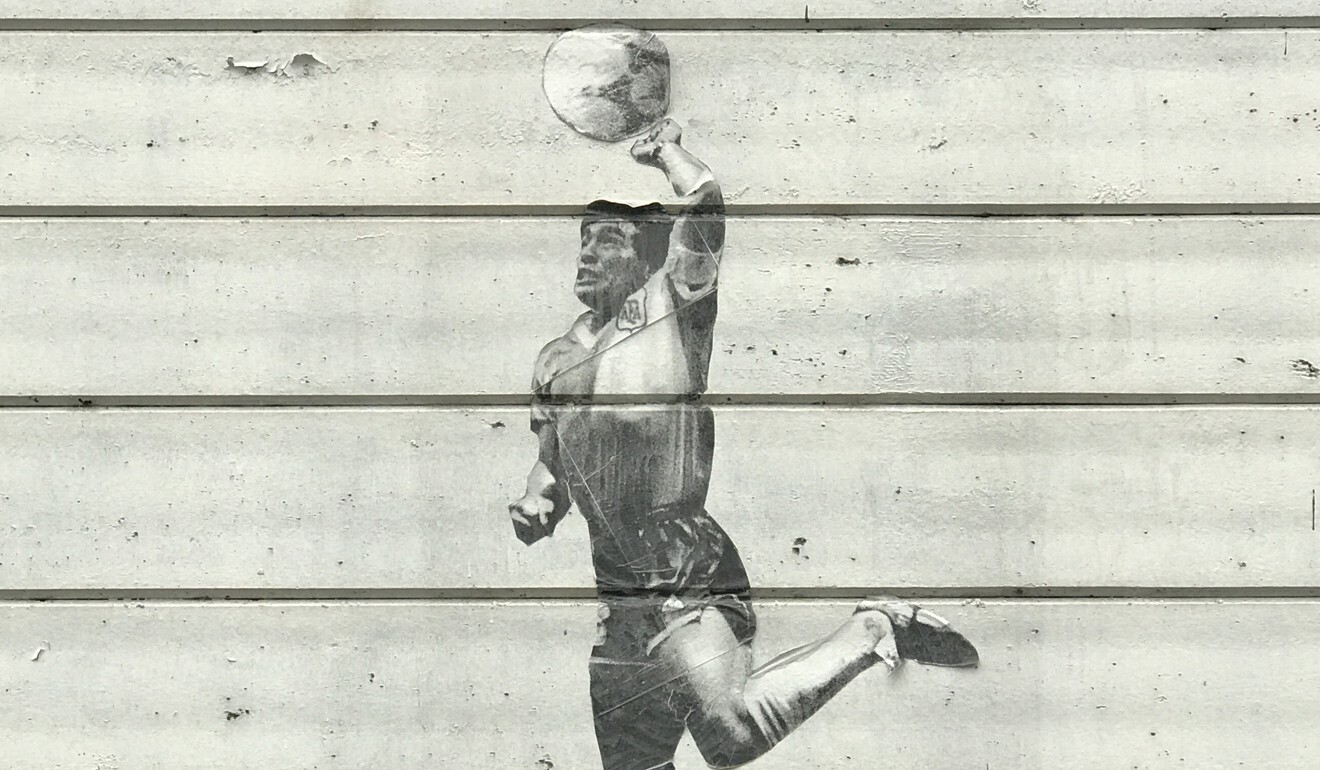

Maradona was also ball boy and would do tricks at half-time to entertain the crowd. He was so good that fans at one game against Boca chanted ‘Let him stay!’ In one youth game, he scored with his hand in a similar manner as his famous goal against England. The referee allowed it to stand and mayhem ensued. He knew what was coming years later.\

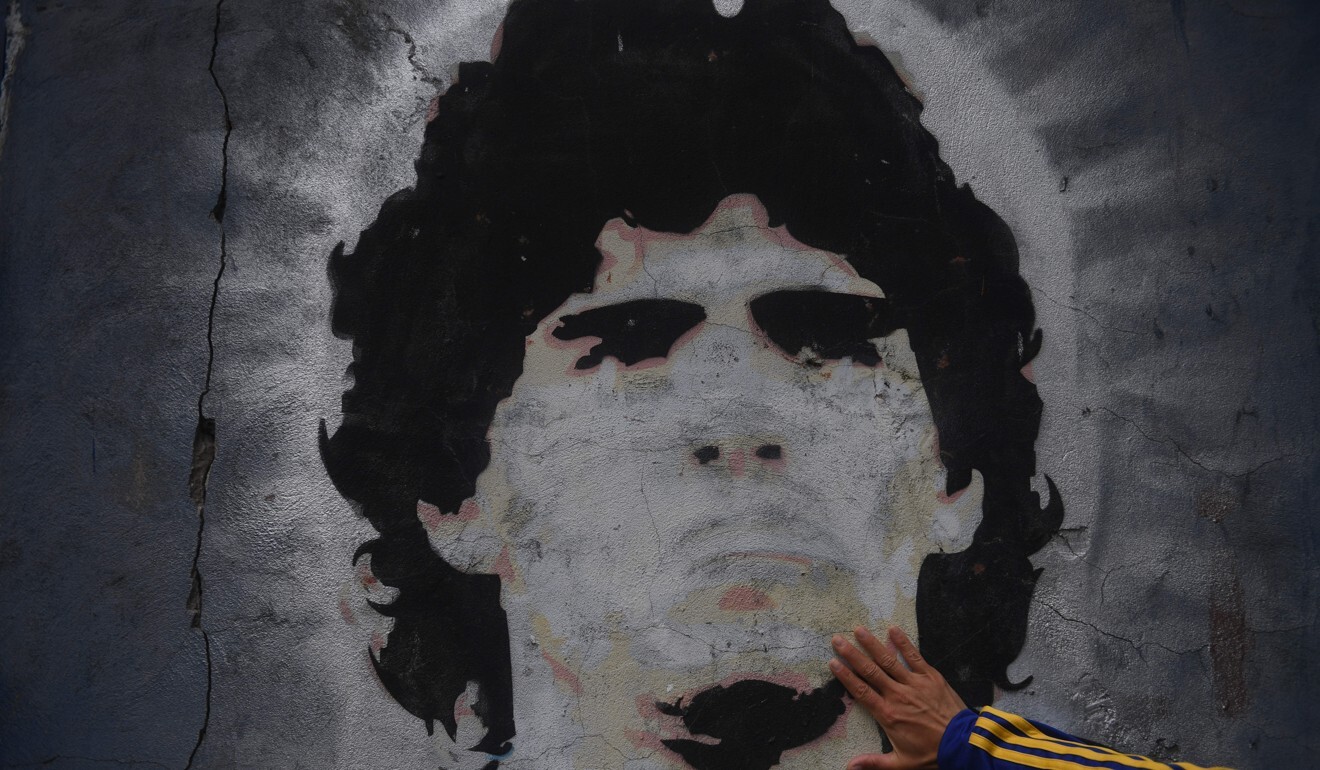

Outside, on a street corner of dense, low rise housing which presses against the stadium, there are numerous street art images of El Diego – as a kid, an adult, lifting the World Cup, the ‘Hand of God’ moment. Fans still sing about him in games, they wave flags.

Maradona made his first team debut at this stadium at the age of 15 in 1976, the year the club rented a nearby apartment for him and his family. His aim was to buy a pair of trousers with the appearance fee and he remembered the streets outside the stadium being full of away fans from Cordoba, a seven-hour drive away.

In his first-ever touch in professional football, Maradona nutmegged an opponent. The secret was out and he said so many people later claimed to be at the game that Rio’s vast Maracana wouldn’t have been big enough to hold them all.

Within a month, Maradona was scoring in Argentina’s top division. When Boca Juniors’ goalkeeper Hugo ‘The Madman’ Gatti called him fat, Maradona put four goals past him in a game. Within four months, he had made his Argentina debut under Cesar Luis Menotti.

“At that age most kids hear stories, he hears ovations,” wrote one newspaper as he started to attract attention, which made him uncomfortable. He would get nervous in interviews, it was all happening too fast, but at least they knew his name.

Leading Argentinian newspaper Clarin first mentioned him at the age of 11, mistakenly calling him ‘Caradona’ after saying the boy “had appeared with the demeanour and class of a star”.

Maradona scored more goals for Argentinos Juniors than he did for Boca Juniors, Barcelona, Napoli, Sevilla or Newell’s Old Boys (where one end of the stadium is named after him). He made his debut for Argentinos Juniors in 1976, left for Boca in 1981 and for Barcelona in 1982, the year of the Falklands War between Great Britain and Argentina.

There are reminders of this conflict all around the stadium which takes his name. Maradona would train at Malvinas (Falklands) training ground from the age of eight, a two-hour bus ride from his house. When he came for trials, they thought he was so talented that he must be lying about his age and insisted on ID.

Today, there is a sports hall named after the Malvinas and flags around the pitch. War veterans are honoured at games. Animated fans sing ‘If you don’t dance you’re an Englishman’ to this day in a stadium where the noise of 8,000 matches 40,000 in a European venue. The issue remains very real.

Maradona really wanted to beat England in the 1986 World Cup finals, but in 1980, two English clubs had tried to sign him.

“Sheffield (United),” he said when I asked him about the subject last year. “And Arsenal. Both. But El Flaco (‘The Skinny One’) Menotti wouldn’t let me. He said I was too young. He was my coach for Argentina’s youth team and we won the World Youth championship in 1979. He said I was better staying with Argentinos Juniors, so I did.”

Maradona ended up in Barcelona, the most expensive player in the world, yet one who was bankrupt by the age of 25 when he moved to Napoli for another world record fee. His agent had invested his riches. Badly. He had met that agent as a 14-year-old on the streets close to Argentinos Juniors stadium.

Fans came back to the stadium which bears his name on Wednesday, sang songs (about the English), lit candles and laid flowers by the many images of El Diego around the stadium.

“Argentinians realised just how popular he is around the world on Wednesday,” says Arca, now living back in Buenos Aires. “He had the heart of every Argentinian, he was so familiar he felt like a family member. Journalists were crying on TV – and not just the sports ones.”

‘Thanks for the magic!’ read one message outside the stadium. And another said it all, “Goodbye God!’