Expect cold that scares you and terrifying tension of encroaching ice in rowing the Northwest Passage, warns polar pioneer

- Paul Ridley and his team are the first to row in the Arctic, in 2012, and though surrounded by beauty the dangers put him on edge for 41 days

- SCMP reporter seeks advice as he attempts to become the first person to row the Northwest Passage in 2021

As Paul Ridley and his team cast off from Inuvik, Canada, in 2012 to be the first to row the Arctic Ocean, you would be forgiven for thinking he was experienced enough to know what was coming. As the youngest American to row solo across the Atlantic in 2009, aged 25, he had months of sea time under his belt.

“On another route, like the Atlantic, you can get more wind or more seas on any given day, but there’s no ice, there’s not a third factor,” Ridley said. “I was terrified pretty much the whole time.”

Ridley, who now lives in Hong Kong, and the team – Collin West, Neal Mueller and Scott Mortensen – spent 41 days at sea and covered 2,000km. They intended to land at Providenya in Russia, but the weather forced them to change destination to Point Hope, Alaska. It was far longer at sea than they had expected, as they faced head winds the entire time.

But being the first – only a few ships had sailed through – there was little to no weather data for them to draw on. In fact, there was not even a clear definition of what constituted rowing across the Arctic Ocean.

“The compelling thing about it was it was the challenge from the planning perspective and the rowing perspective,” he said. “The first thing was how we’d even know if we had rowed across the Arctic and what that even means. How do you define ‘across’ and how do you define ‘Arctic Ocean’.”

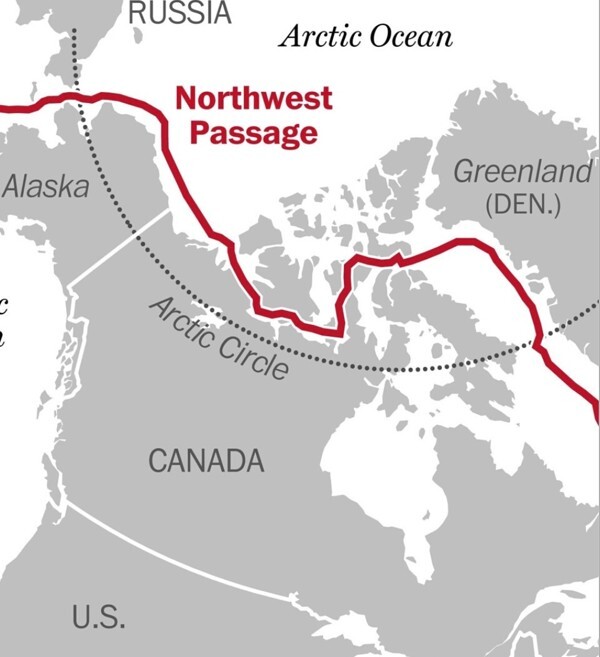

Having finally settled on a route that they thought met both terms, they set off. The trials and tribulations at hand were as gruelling as any expedition. And now he is sharing those lessons with another team, including this author, as they aim to be the first people to row through the Northwest Passage in 2021 – the 4,000km Arctic route that links the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Climate change gives adventurers one last great first

The last few hundred miles of the Northwest Passage row will cover much of Ridley’s same route.

“We were dodging ice all the time. We were caught in ice multiple times,” he said.

“It’s pretty tense to be honest. There are a few days I think of when we were locked in ice and fog. We were rowing through incredibly narrow passages in the ice, a lot of them were just wide enough for our oars to still be rowable.”

“Visibility was zero and you know there are polar bears out there. You feel lucky to be the one going to sleep at the end of your shift. That time is very tense.”

The main contrast to the Atlantic is the difficulty establishing a routine. With the ice disrupting shift patterns, the rowers had to constantly adapt and stay alert.

“It is very much mentally draining,” Ridley said.

Ridley remembers that no matter how warm they were from rowing, their feet always suffered. They each came up their own solution. He crumpled up the foil bags from their dried food rations and stuffed them in his boots. It alleviated the issue but never solved it.

“It is a scary kind of cold. You’re not that cold all the time, but everyone in the crew had moments when they were scary cold.”

They would boil water and place water bottles under the suffering teammate’s armpits and neck.

“You have to count on your team when it happens,” Ridley said.

“We found that it happened when someone was fatigued, or lazy. When you are getting ready for your shift, if you take a couple of extra minutes before you get dressed and it means you miss one of the layers on your feet, for example, then you are not ready for a four-hour rowing shift in the Arctic.

“It was things like that which got you into trouble – looking after yourself is incredibly important, not just to ease the pain of being cold for a shift, but it’s dangerous if not everyone on board can row.”

“When we did that row in the summer of 2012 it turned out to be a record low year for Arctic ice and since then almost every year has been a record low year.

“One of our goals was to bring attention to that fact. It is now rowable and it shouldn’t be, and it’s getting worse. The cause is still there, and the need for people to be aware is still there, so in that sense I’d do it again,” he said.

‘10 days feels like a month’: team rows to Antarctica

“But from the perspective of going up there and being on the oars for 12 hours a day, with four other guys on a boat not really built for that, it would be a long time before I choose to do that again for fun.”

Above all, he remembers the incredible First Nations and Inuit people who he met at the start and finish. The latter put on a welcome ceremony and shared gifts. And the beautiful landscape will forever be etched in his mind, especially on the clear days when the sunset would last for six hours.

“It’s an incredible part of the world. You’re going to have a blast. It is an experience you’ll talk about for the rest of your life,” he added. “But try to keep your feet warm.”