Remembering the forgotten explorers of the Northwest Passage during Black History Month, the first people to make it from the Pacific to the Atlantic

- Two black men, including an American escaping enslavement, were among the first people to travel from the Pacific to the Atlantic via the Arctic

- The Investigator crew was rescued while searching for Franklin’s famous lost expedition

Two black men were part of the first crew to travel from the Pacific to the Atlantic via the Arctic, but have drifted into obscurity amid the more famous stories of the Northwest Passage.

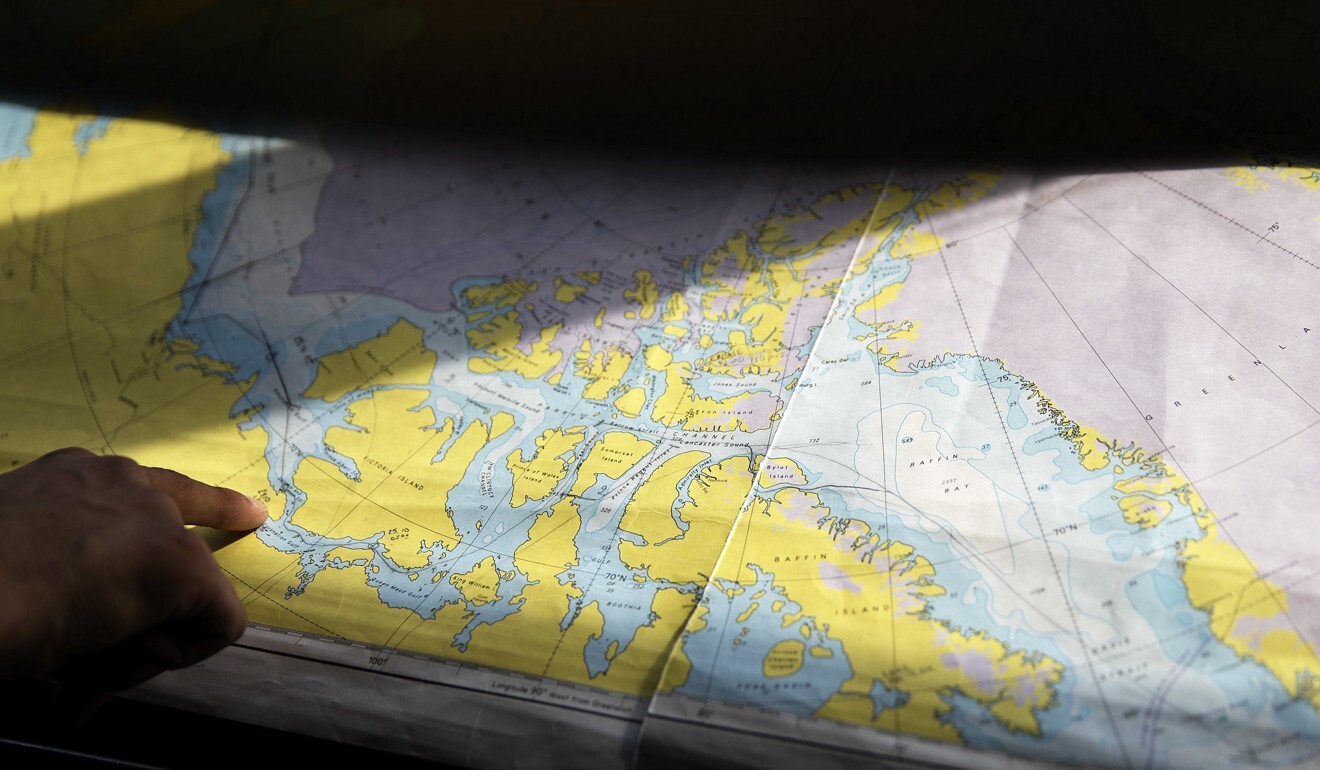

For centuries, Britain searched for a water way linking the Atlantic to the Pacific over Canada and Alaska. The hunt for the Northwest Passage turned into a national obsession in the 19th century. When one of Britain’s most famous explorers, John Franklin, failed to return from his 1845 attempt to locate the Northwest Passage, countless expeditions were sent to rescue him, even long after it was clear he had perished.

Among the search and rescue expeditions were the ships the HMS Enterprise and the HMS Investigator. On their second expedition, they entered the Arctic via the Pacific in 1850, through the Bering Strait between the tip of Alaska and Russia.

Robert McClure, commanding the Investigator, was hell-bent on becoming the first person to find and make it through the Northwest Passage under the guise of rescuing Franklin. Despite the expedition leader, Richard Collinson, being on board the Enterprise, McClure wanted the glory for himself.

The pair became separated even before they entered the Arctic. McClure’s ambition saw him sail his crew into a torturous four years. McClure proved to be a tyrant of a captain, inflicting harsh floggings, tough rationing and imprisonments. Even when it was clear all was lost, he was blinded by his ambition and tried to press on. The expedition cost five of his 66 crew their lives.

Among the crew was Gunroom Cook Charles Anderson, a black man and possibly an American escaping enslavement. He said he was from Port Robinson, in Canada. Thousands of escaping enslaved people made it over the border to Canada. There were very few black people in Canada at the time who had not come from America. At the very least, Anderson’s assertion that he was from Port Robinson suggests his parents had escaped enslavement, according to Discovering the North-West Passage, a book by Glenn M. Stein.

First black person to row an ocean aims for another historic voyage

Also on board was Coxswain Cornelius Hulott, another black – or possibly mixed-race – man, who was from Kent in England. In the 1850s, to have black explorers aboard was very unusual. The two pioneering sailors were to become part of history.

After entering the Artic in 1850, the Investigator went between Victoria Island and Banks Island into the Prince of Wales Strait, which they found blocked by ice. Here, the crew spent their first winter in the Arctic, their boat encased in ice.

While trapped, McClure sledged to the north east coast of Banks Island, and looked out across a stretch of ice-chocked water. On the other side was Melville Island, which had been reached by previous explorers entering the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic. This sighting proved the existence of the passage, and thus, after centuries of searching he had finally found what so many had looked for.

The ice was unrelenting even next summer. The crew managed a short sail back on themselves and then tried to go around the north of Banks Island, only to become stuck in the ice again. They were to spend their second winter in the Arctic.

The men were beginning to starve. Scurvy was rife. The summer passed and the ice did not melt. By 1853, little hope remained but McClure was not ready to give up on his dream of making it through the Northwest Passage.

He devised a truly horrible plan. He would send an overland party to find help. He picked the 30 weakest, sickest men, and chronically undersupplied them for their journey. It seemed he was sending them on a suicide mission so he did not have to waste precious rations on the weak.

Is BBC drama ‘The Terror’ a true story of Northwest Passage exploration?

Their luck changed in time to save 29 of the 30 would-be dead men walking. One of the sledging party died of scurvy before departing. The crew made a crude grave, hacking away at the frozen soil of Banks Island.

As McClure and one of his officers walked across the ice discussing the funeral plans, they spotted a loan walker but dismissed him as one of their own returning from a hunting party. In fact, it was Lieutenant Pim, of the HMS Resolute, under the captaincy of Henry Kellett. There were five other ships in the Arctic, under the overarching command of Edward Belcher (the first Briton to survey Hong Kong Island), all searching for Franklin and now McClure too. McClure and his crew were to be rescued.

McClure saw things differently. The Resolute could take the sickest of his crew, and he could continue with his attempts to make it through the Northwest Passage. The captain of the Resolute almost agreed, but when he saw the state of McClure’s crew – “some blind, some insane, some lame, all of them scorbutic and several suffering from frostbite”, according to Barrow’s Boys, a book by Fergus Flemming – the captain refused McClure’s plan.

A cold that scares you and terrifying tension in rowing the Arctic

In the meantime, two more of McClure’s crew died. The Resolute’s captain, Kellett, openly blamed McClure’s starvation rationing for the latest deaths. Even after a doctor told McClure that heading on would mean certain death by scurvy, even for the healthier crew members, McClure would not abide. He called the 20 healthy crew members on board and asked anyone willing to continue to step forward. Only four did so. He finally relented.

The Investigator was abandoned. The ailing crew moved to the Resolute and began their journey home, only for the Resolute to become frozen in ice again. And so, in 1854, McClure and his crew spent yet another winter in the ice.

For the two black members of the crew, they were forced to face other indignities on top of their communal suffering.

To pass the time, the crews of the ships performed shows. During one performance, the crew put on blackface and sang songs. Anderson was part of the performance, according to an essay in the encyclopaedia of the Arctic, by Jonathan M. Karpoff.

On another occasion, when the Investigator was trapped, Anderson had become lost on a hunting party. He was found by one of the Marines, called Woon. The pair continued to try and hunt deer but the cold got to Anderson – he was overcome with fear and fatigue, and Woon had to coax him back to the ship.

Anderson’s reaction might seem normal for someone who had endured starvation and cold, but the doctors aboard had other interpretations.

“The incident furnishes a striking proof of the difference in moral and physical powers of endurance of the dark and white races,” wrote the ship’s surgeon, according to Discovering the North-West Passage.

Another officer wrote the event showed “a remarkable superiority of spirt and energy in the white man over the black”.

The winter of 1854 came and went, but the ice remained. The Resolute was abandoned and the crew made one final, arduous, overland journey to Beechey Island, where the other ships were hunting for Franklin.

Documenting melting ice in the Northwest Passage

McClure and his crew were divided up among the remaining ships and exited the Northwest Passage, finally. Thus, they made the first traverse of a Northwest Passage. Hulott had lost several toes to frostbite. He carried on working in the Royal Navy as a rigger on the Isle of Sheppey, in England, according to a press release by Blue Town Heritage Centre.

As for McClure, he was awarded the £10,000 prize by the British government for being the first to make it through the Northwest Passage. The money was split, half going to McClure and half to his crew. But as he had traversed so much of the passage by foot, and in multiple boats, it was considered controversial to acknowledge his achievement. But the British government wanted the hunt for the Northwest Passage to end, as it was draining their funds and they were at war with Russia.

Simultaneously, explorer John Rae was searching for Franklin’s expedition. During his 1853-54 expedition, he found a body of water that was the final puzzle piece for the Northwest Passage, south of Victoria Island and Banks Island (as opposed to McClure’s route which went north). Rae was given £10,000 for finding evidence of Franklin’s fate, and is generally considered the discoverer of the Northwest Passage, and McClure, the discoverer of a Northwest Passage (the distinctions are fairly arbitrary).

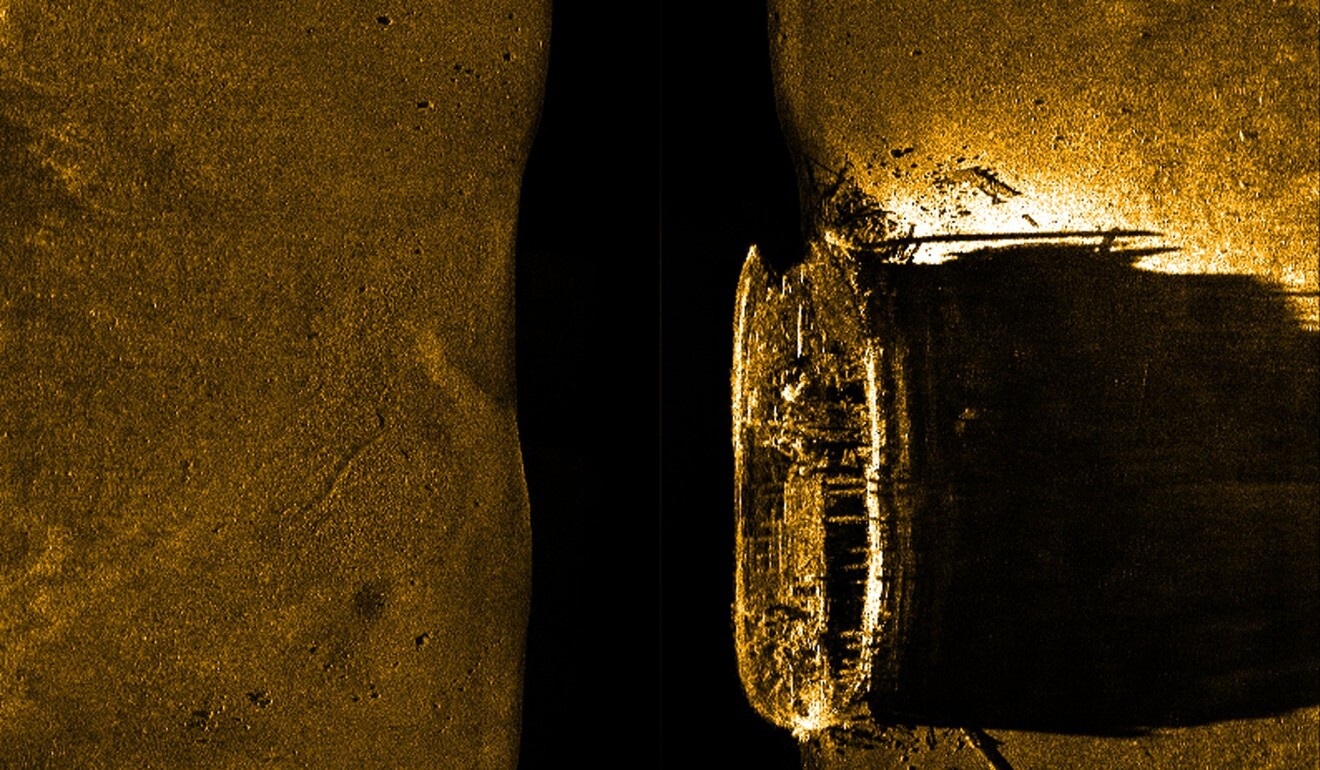

As for the Resolute, it was found by an American whaler and gifted back to the British. The British in turn broke it down and used the wood to make a desk, which they gifted back to the Americans. The Resolute Desk is still the presidential desk in the Oval Office in the White House. The Investigator’s wreck was found in 2010.

By comparison, the strange and horrific expedition lead by McClure, and the two pioneering black sailors, drifted into obscurity.