Explainer | US-China tech war: Everything you need to know about the US-China tech war and its impact

- Analysts generally point to Beijing’s Made in China 2025 program as the trigger for the tech war

- The Biden administration has kept up the pressure on China tech and in the case of Huawei, increased it

In fact, Biden has cast US competition with China as the most important front in a generational struggle between democracy and autocracy.

US-China tech war: calls for more tech bans on China get louder in Washington

The tech war started as a trade dispute, but soon morphed into a battle for leadership in core technologies like 5G, artificial intelligence (AI) and semiconductors.

The US, with its long history of R&D and invention, has been the global tech leader for decades, but that position is now being challenged by China, which has thrown its full weight - and tens of billions in state funding - behind efforts to catch up to the US.

After Washington began blocking China’s access to core US-controlled technologies like semiconductors, Beijing doubled down on efforts to “de-Americanise” its supply chain.

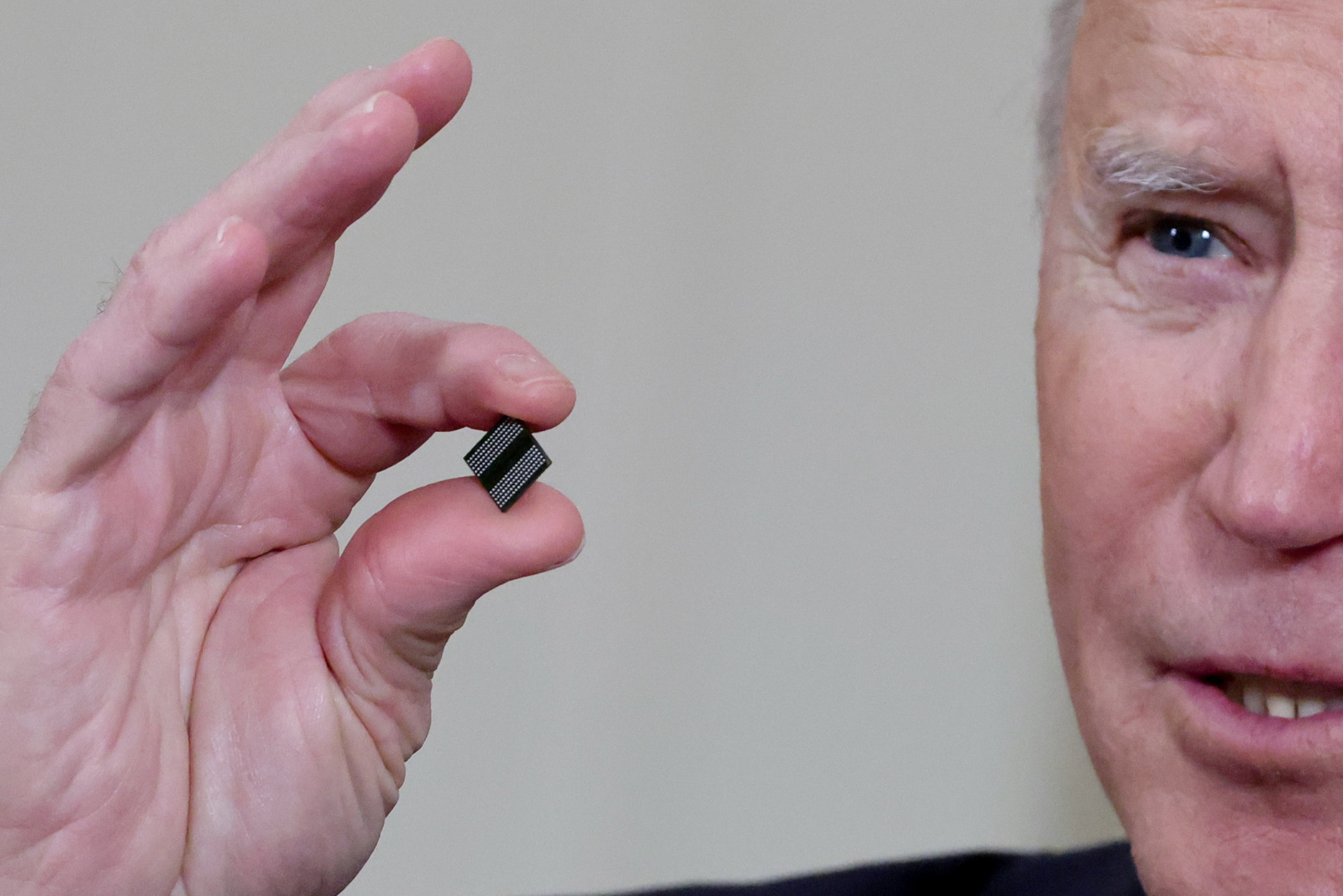

The global pandemic contributed to tensions between the two nations, prompting Biden to issue an executive order to review US supply chains for core products like chips, batteries, rare earths and medical supplies.

Bills proposing significant increases in US investment and R&D spending in core tech have also received bipartisan support in Washington.

This explainer seeks to answer some of the key questions about the US-China tech war - a conflict that at this point has no end in sight.

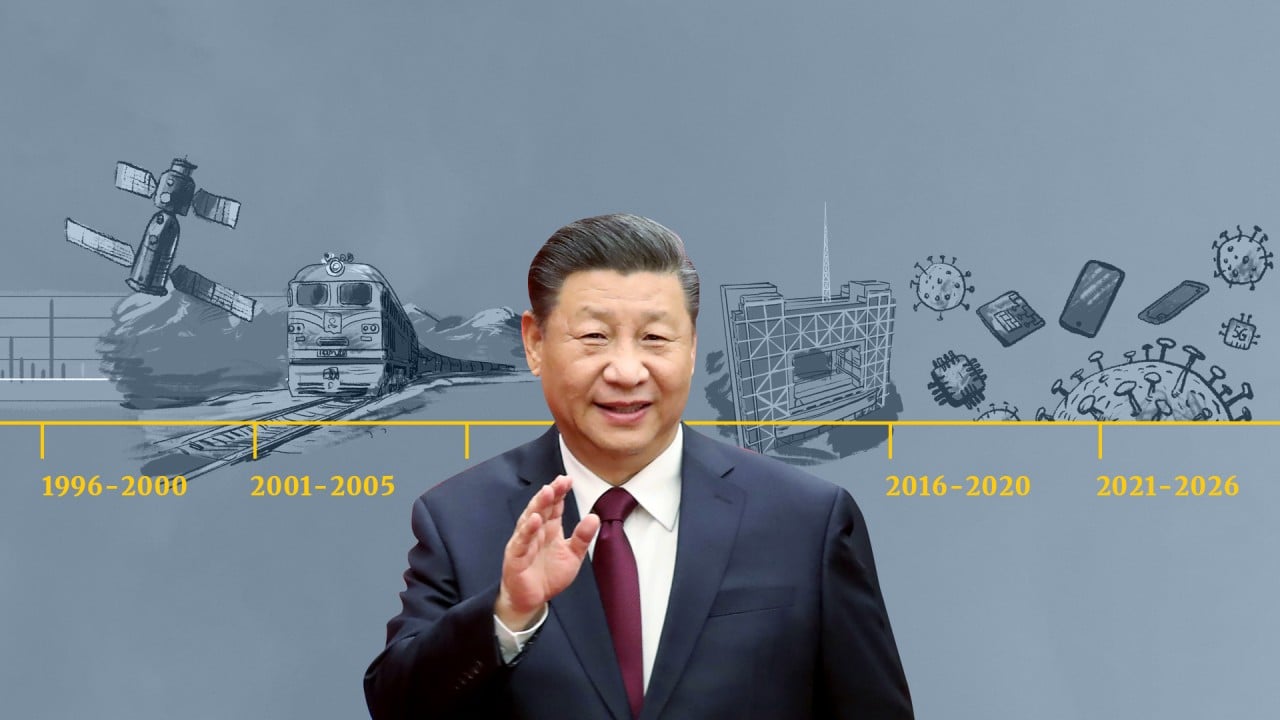

What triggered the tech war?

Analysts generally point to Made in China 2025, Beijing’s 10-year blueprint for transforming the country from a “manufacturing giant into a world manufacturing power”, as the trigger for the tech war – only it was a delayed reaction on the part of the US, which was preoccupied with the 2016 presidential election campaign when MIC 2025 was announced in 2015.

What is the difference between the trade war and tech war?

The US-China trade war started on July 6, 2018, when US President Donald Trump imposed a 25 per cent tariff on US$34 billion of Chinese imports, citing the need to “rebalance” the growing US trade deficit with China. Further tariffs were imposed during 2018 and 2019.

However, the trade war was soon overshadowed by a tech war driven by US concerns that China was using unfair means, including state power and IP theft, to achieve its goal of becoming a global leader in core technologies like AI, semiconductors and 5G.

What is decoupling and what would it mean if it actually happens?

In the decades after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, the American and Chinese economies became intertwined. China was the low-cost workshop for American products, from computers to stuffed toys.

Initially, decoupling was dismissed as unrealistic because China was too big for US companies to ignore, and its economy was too intertwined with the global economy to be walled off.

However, a limited form of decoupling gained bipartisan support, even from tech leaders like former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, who joined an informal working group of Washington and tech insiders in saying a certain degree of “bifurcation” would be in US interests.

That already exists to a large degree in the internet space, with Facebook and Google not allowed to operate their social network and search engine in China, and attempts under the Trump Administration to ban or restrict the US presence of Chinese social media like TikTok and WeChat.

What is China doing to ameliorate the impact of the US actions?

Although China imposed retaliatory tariffs at first, the main response was the top leadership’s call to action for tech self-sufficiency. In the summer of 2018, President Xi Jinping said “China must stick to the path of self-reliance amid rising unilateralism and protectionism in the present world.”

After Huawei was blocked from buying US chips and Shanghai-based foundry Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC) was restricted from buying US technology for alleged links to the Chinese military - a charge it denies - Beijing intensified its focus on achieving semiconductor self-sufficiency.

However, analysts pointed out that such a goal was unrealistic given the significant investments required to replicate each part of the existing global chip supply chain.

Under the Vision 2035 development strategy, unveiled along with the 14th Five-Year Plan, resources will be poured into seven scientific areas, including AI, quantum information and semiconductors.

What role do technologies like 5G and semiconductors play?

That development is expected to rev up digitisation across traditional industries, which is projected to yield more than 10 trillion yuan in growth over the same period.

Initial commercial 5G mobile services were rolled out last year in South Korea, the United States, Australia, Britain, Switzerland, Spain and Monaco. Yet the scale of China’s market is likely to dwarf the combined size of those economies, negating any first-mover advantage.

Semiconductors are the core technology behind everything from smartphones to spacecraft. Despite pouring billions of dollars into the sector over the decades, Chinese companies have struggled to catch up to global leaders like US-based Intel, South Korea’s Samsung Electronics and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), all of which are investing billions of their own money into pushing the boundaries of physics and materials science.

Semiconductor design and production is a notoriously complex business, involving decades of expertise and extreme precision. Getting it wrong can mean billions of dollars of investment going up in smoke - as China has experienced a number of times, most recently with the Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (HSMC) chip project in Wuhan.

Why did the US specifically target Huawei with trade sanctions?

Washington’s concerns over Huawei date back to the early 2000s, and were largely driven by the belief that the Chinese company had close ties to the Beijing government. Years later, Huawei’s emergence as a global leader in 5G technology set off alarm bells in Washington.

One of the first public moves against the company came in January 2018 when US lawmakers pressured American telecoms giant AT&T to pull out of a deal to distribute Huawei smartphones to US consumers. Seven months after the AT&T decision, Washington barred government agencies from purchasing equipment and services from the Chinese company.

When Huawei was added to Washington’s Entity List in May 2019, banning it from buying products and services from US companies without US government approval, the US Department of Commerce said Huawei and its affiliates were “deemed to be involved in activities … contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States”.

Washington also alleges that Huawei contravened US sanctions against Iran, leading to the arrest in Vancouver of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in December 2018 on bank fraud charges. She is currently fighting extradition from Canada to the US.

What impact have the sanctions had on Huawei?

Initially, the entity list sanctions seemed to have little impact on Huawei, which reported record revenue of 858.8 billion yuan in 2019, up 19.1 per cent year on year.

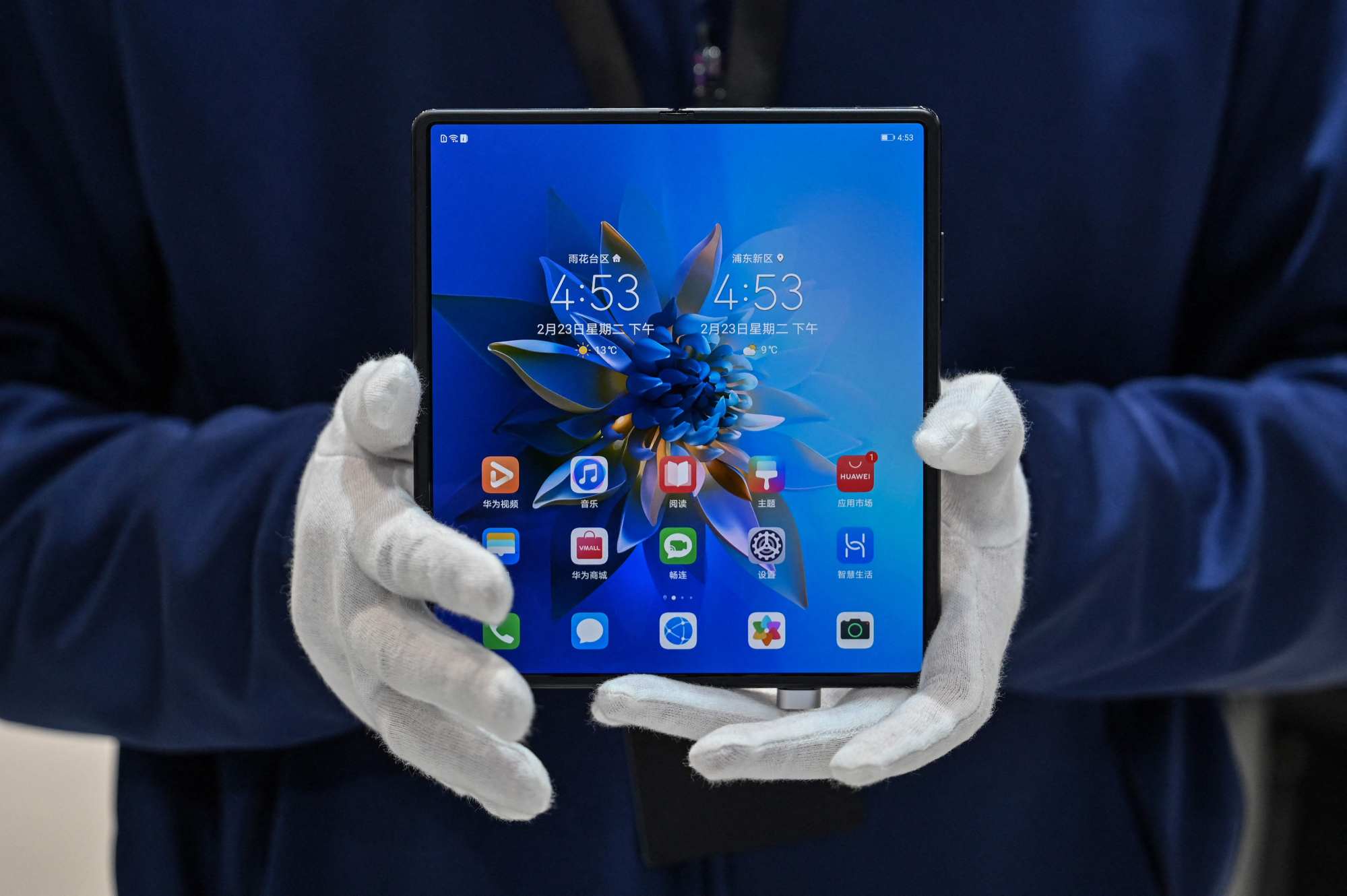

It also quickly unveiled a self-developed operating system called Harmony OS, which had been in the works for some time but was fast tracked to be ready to install on handsets if it lost access to Google’s Android.

However, after Washington expanded the reach of its sanctions in May 2020, requiring foreign chip makers that use US technology to apply for a license to sell chips to Huawei, the Chinese telecoms giant appeared to be on the ropes.

The biggest hit was to Huawei’s smartphone operations, which were starved of high-end semiconductors, and led to the company’s decision in November 2020 to sell its Honor budget smartphone business to a consortium of over 30 agents and dealers.

Huawei subsequently tumbled in the rankings of global smartphone brands in the fourth quarter last year, to No 6, according to research firm Counterpoint.

When 2020 numbers were in, they showed that Huawei’s annual revenue growth had slowed to its slowest in a decade, up only 3.8 per cent to 891.4 billion yuan.

Bryan Ma, vice-president of client devices research at IDC, said there will definitely be downward pressure on Huawei’s consumer business group this year, not only due to its dwindling stockpile of smartphone components, but also because the Honor business will not be a contributor anymore.

What other Chinese companies were targeted (and why)?

In October 2019, the US Commerce Department added another 28 Chinese public security bureaus and companies to the trade blacklist, over Beijing’s alleged human rights abuses of Uygur Muslims and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities.

The companies added included facial recognition start-ups SenseTime, Megvii and Yitu, video surveillance specialists Hikvision and Dahua Technology, AI champion iFlyTek, Xiamen Meiya Pico Information Co and Yixin Science and Technology Co. It was alleged that technology provided by these companies was complicit in the human rights abuses.

In May 2020, two dozen government institutions and Chinese companies, including the software giant Qihoo 360 Technology, were sanctioned for “supporting procurement of items for military end-use in China”.

Will the tech war be any different under a Biden administration?

In a word, no. Other than putting a hold on the Trump administration’s attempts to ban Chinese short video platform TikTok and social media app WeChat in the US, Biden has kept up the pressure on China tech and in the case of Huawei, increased it.

In March, the US Commerce Department further restricted what US companies can sell to Huawei, with more explicit prohibitions on the export of components like semiconductors, antennas and batteries that can be used in Huawei 5G devices.

A day later, the US Federal Communications Commission designated five Chinese tech firms, including Huawei, ZTE, Hytera Communications, Hikvision and Dahua, as an “unacceptable risk” to national security.

With regard to Huawei, analysts believe Biden may be more effective than Trump in curtailing its global 5G ambitions by taking a friendlier approach towards international partners in Europe and elsewhere. That could be more effective in isolating the Chinese company.

Besides sanctions on individual Chinese tech companies, Biden has cast US competition with China as the most important front in a generational struggle between democracy and autocracy. He has also pledged to more than double the amount of investment in science and technology as a percentage of GDP, focusing on areas like AI and quantum computing.

Biden’s ambitious US$2 trillion plan to improve US infrastructure includes an estimated US$50 billion to help the country become less reliant on chips made overseas.