Advertisement

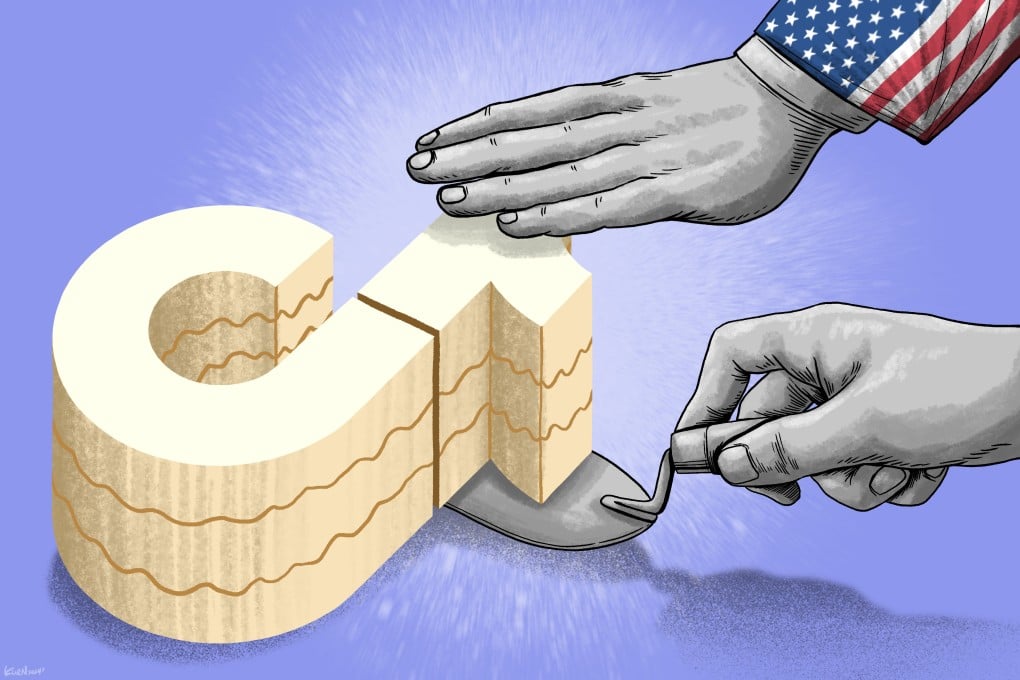

US lawmakers want a TikTok sale or ban, but China’s ByteDance won’t give up without a fight

- From lobbying politicians to rallying users, ByteDance and TikTok have put up stiff resistance to divestment pressure in the US

- In addition to dealing with mounting political hostility in Washington, ByteDance also has to assuage concerns in Beijing

Reading Time:6 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

45

Coco Fengin Beijing

Zhang Yiming, the 40-year-old Fujian province native who founded ByteDance in a Beijing residential flat 12 years ago, is one of the most successful entrepreneurs the world has seen in the last decade, on a par with Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg and Sam Altman.

But the Chinese billionaire, who has rarely been sighted in public since handing over the reins of the company to his university roommate Liang Rubo three years ago, is the most reclusive among his peers, even as his company takes political heat in both the US and China.

After the US House of Representatives passed a bill on Wednesday to force ByteDance to divest TikTok or face a ban in the country, speculation has been rife about whether Zhang might consider ceding Chinese ownership of the popular app to American buyers – or whether such a move is even possible.

The bill is headed to the US Senate, where both Democratic and Republican leaders have rejected the idea of fast-tracking its passage.

While US President Joe Biden said last week he would sign the bill into law if it passes both chambers, ByteDance and TikTok can still challenge the divestment order in US courts.

In a video published on the platform, TikTok CEO Chew Shou Zi, a Singaporean citizen, called the House decision “disappointing” and vowed to “continue to do all we can, including exercising our legal rights”.

Advertisement