All hail South Korea’s sharing economy (except its taxi drivers)

- Cabbies protesting against a car-pooling app by Kakao are fighting a losing battle.

- The tech savvy country finally appears to be embracing the sharing economy – and not even its chaebol firms are immune to change

Don’t tell its long-suffering taxi drivers, but Seoul may finally be ready to embrace the sharing economy.

Granted, that’s not the impression casual observers will have had earlier this month when taxi drivers filled the streets outside city hall to protest against Kakao, makers of the latest ride-sharing app that provoked their wrath.

The protest was eerily reminiscent of the ones that helped slam the door on ride-hailing giant Uber back in 2015 and served as a reminder of the many roadblocks Mayor Park Won-soon has faced in bringing the capital city up to speed with the transport revolution taking place in much of the rest of the world.

The cabbies are now waiting on the government to decide Kakao’s fate, but this time around politicians may well be on the side of innovation, especially because the app in question comes from a home-grown tech company.

“This time the sentiment is so different,” says Joseph Lim, a visiting professor at Yonsei University who advises start-ups in Seoul and works as an innovation officer at the World Federation of United Nations Associations. “Last time they protested, Uber was definitely out.”

Polls show that a majority of South Koreans – 56 per cent – support Kakao, which markets its latest app as a carpooling service rather than a taxi-hailing one.

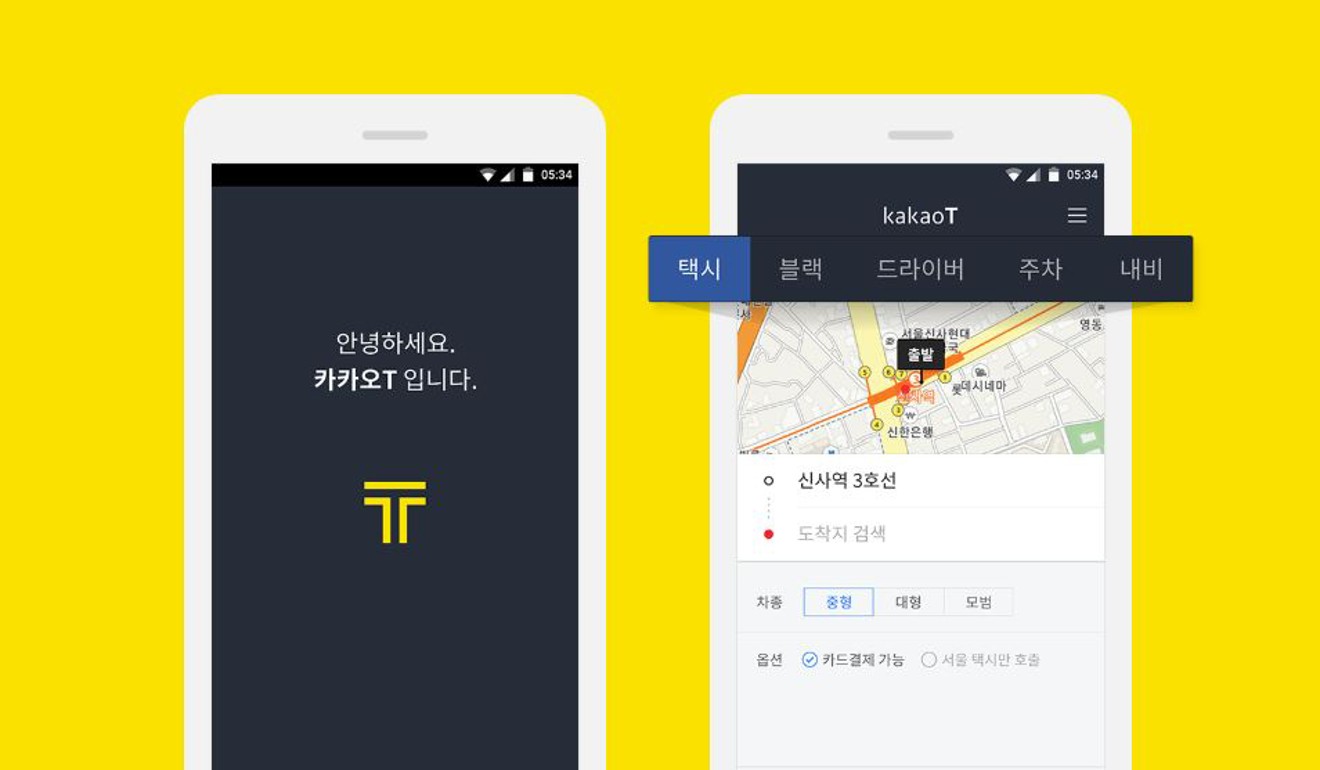

The company started out as South Korea's largest messaging app, making a foray into taxi-hailing in 2017 by using its platform to connect riders with taxis.

Now Kakao has found a loophole that should enable its carpooling app to avoid the same fate as Uber, by offering its service to commuters during specific hours.

South Korean law forbids private vehicles from being used for business purposes – but it makes an exception to help ease traffic burdens during “commuting hours”.

Fortunately for Kakao, the law fails to state when those hours start or end.

Commuting hours in Korea are generally considered to be from 5am to 11am and 5pm to 2am, opening a large window for Kakao’s carpooling service to operate in if government policies allow it.

SHARING THEIR SUCCESS

But hopes to boost the sharing economy in Korea go beyond Kakao. Politicians including Mayor Park are looking to cultivate new businesses that can shift the economy away from an over-dependence on chaebol (family-run firms) such as Hyundai and Samsung.

For a tech-savvy nation, South Korea has so far been surprisingly resistant to developments that could disrupt key industries, making it hard for brands like Uber, Airbnb and even local start-ups to gain a foothold.

Lim thinks a part of this is due to Korea’s size.

“Korea is a small enough economy that a significant few can get together and have enough of a force to hold off the incoming technology,” he says.

Much like the taxi drivers, Korea’s older chaebol, pillars of the “miracle economy” that helped take South Korea from a war-torn country to one of Asia’s wealthiest, have proved resistant. With change on the horizon, chaebol are accused of using their influence to resist the disruptions that Mayor Park insists Korea’s economy needs.

“They all have a position in Korean society that doesn’t want change to come, because there’s already a profit-making model,” Lim says.

The government sees innovation as part of its economic strategy, and is pouring big money into start-ups while counting on innovation from companies such as Kakao.

But too much government funding is creating its own problems in Korea’s start-up scene. Grant money comes hand in hand with the same bureaucracy that makes governments so slow to innovate.

It’s weighing down start-ups when they should be at their lightest and fastest.

“What happens is … instead of being start-ups, they become like mini government agencies operating in the way the government wants. It wants you to be more rigid, more formulated, more predictable,” Lim says.

Things are no easier for foreign companies looking to enter the Korean market, as Uber found out in 2015 and Airbnb in 2016. Airbnb faced huge roadblocks when a long list of regulations and older landlords fearing change made it difficult to operate, leading them to delete some 1,500 listings deemed illegal.

Even Google has shockingly low user rates among Koreans, partly a result of local search portal Naver’s efforts to keep them out. Despite calls for innovation, the walls around South Korea’s market are still high. At least part of the problem is the way newer companies and start-ups come to the Korean market unprepared.

“Big corporations when they approach the Korean economy work in one way. But start-up companies … it’s hit and miss,” Lim says. “They pull people from everywhere, but they’re not particularly the best people to start a competitive service in the Korean context.”

Still, even for local Korean companies who “get it”, regulations and the dominance of chaebol make Korea a hard market to enter, and may be holding back progress in new industries such as ride-sharing and internet banking.

As a result, Korean entrepreneurs have come up with a new tactic. New companies have to make their solutions “incredibly pointy, and then poke where it doesn’t hurt, as deep as you can”, Lim says. “You have to go unnoticed for a very long time.”

The key is not to alert conglomerates to a threat. Then once the firm is established, it’s time to expand.

It’s the same tactic online payment start-up Toss is said to have used in getting cosy with domestic banks.

And it appears to be exactly what Kakao, though not a start-up, has done to the taxi market.

Kakao Taxi started as a way to help people hail taxis, positioning itself as a business partner helping to modernise the industry. After gaining a foothold as the go-to app for finding a ride – and the trust of the taxi drivers – the company is now using its brand and user base to fuel a new ride-hailing service.

“It started as a win-win for both sides. Good for taxis, and good for Kakao,” says In Yeong-yeol, a taxi driver in Seoul. “There’s been talk of boycotting the Kakao Taxi app, but nothing has happened yet.”

Now that many Koreans rely on the app to order taxis, boycotting the app would mean leaving the one platform where riders go to find them, pushing riders even further away from traditional taxi services.

On their part, young riders complain that taxi drivers have become increasingly choosy about who they pick up when demand is high, making it nearly impossible to catch cabs after midnight in popular night spots.

They also complain that bad service has made them opt for ride hailing services.

Taxi driver In agrees with young riders, who complain about bad service from some taxi operators, particularly when demand is high. But he insists most drivers are not like this and questions what they will do after their low wages are cut even further.

South Korean leaders may be betting on the success of innovative companies like Kakao, as they scramble to do something about the country’s bear market. But as Lim points out, innovation isn’t without its losers.

“When the rubber meets the road, money has to be lost by somebody.” ■