Has the Filipino diaspora fuelled Jollibee’s international growth?

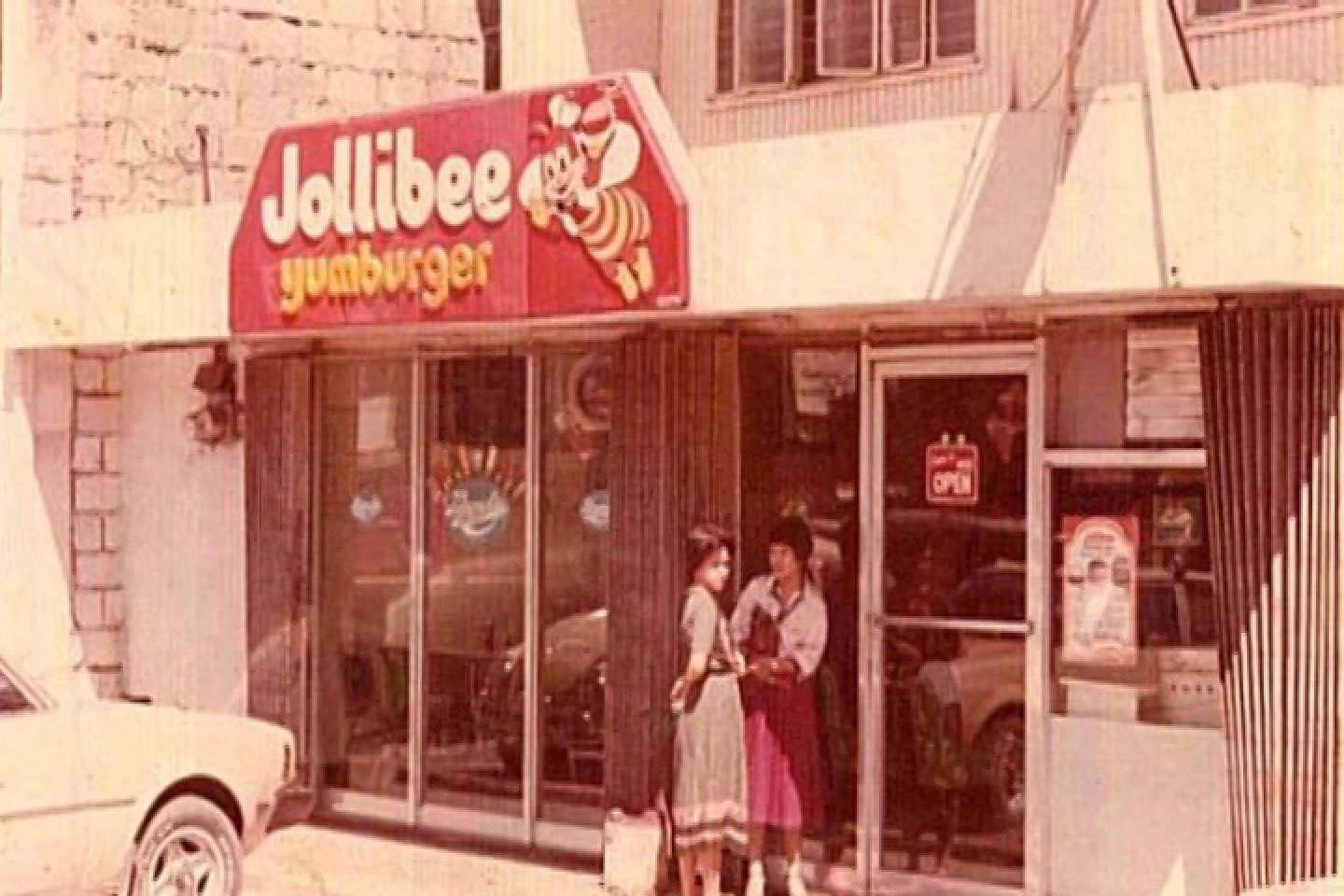

- Started by a Filipino-Chinese entrepreneur in 1978, fast food restaurant Jollibee can today be found in 34 territories

- Its recipe for growth has included foreign brand acquisitions and homesick overseas Filipinos longing for a taste of national pride and Chickenjoy

When Ireland-based Philippine migrant Ramon Borje and his daughter were on holiday in Italy in 2018, they broke away from their tour group in Rome to make a side trip to Milan, three hours away.

The draw? A meal at Jollibee, a giant Philippine fast food chain known for its burgers, fried chicken and spaghetti.

So beloved is the brand, time and distance are minor inconveniences to homesick overseas Filipinos.

How the Philippines’ finest brands took over the world, from fast food to beer

California worker Cristina de Leon said she often made a beeline for the nearest Jollibee outlet despite an abundance of food choices in the US state, while hotelier Rhyan Santos queued for hours for “a taste of home” when Jollibee opened its first branch in the United Arab Emirates.

“The feeling is different the moment you enter Jollibee in a foreign land,” said Borje, who lives in Galway. “In Milan, the staff is so friendly. They were so happy. I feel like I’m back in the Philippines.”

Dishing out joy and happiness was exactly what Tony Tan Caktiong had in mind when he formed Jollibee Foods Corporation (JFC) in 1978 with his wife Grace, brothers Ernesto, William and Joseph, and other relatives.

“In JFC, we made the strategic and disciplined choice of creating joy and happiness through great-tasting food,” the Filipino-Chinese founder told graduates of the Philippine-based Asian Institute of Management in 2019.

What was the original product served by Filipino fast-food giant Jollibee?

Famously media-shy, Tan Caktiong did not respond to a request for an interview with This Week in Asia.

The ever-smiling, boyish-looking businessman appears to prefer opening up to graduates, which he did in 2005 as commencement speaker at the Ateneo de Manila University.

“When I think back on those early days, I can say I had a dream, and it was a pretty big dream,” he said then. “I once boldly stated in one of our early planning sessions that my vision was to create the largest food company in the world.”

Today, Jollibee has not quite achieved this but the flagship store, with its iconic dancing- bee mascot, is now the country’s largest, with 1,184 other outlets nationwide.

There are also almost 300 Jollibee branches overseas, including in Britain, Canada, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore. Vietnam is the only country outside the Philippines to have more than 100 outlets.

The founder’s quest for global domination has included many local and foreign acquisitions under the JFC Group umbrella.

In 2004, it bought Chinese noodle chain Yonghe King, followed by Beijing-based congee chain Hong Zhuang Yuan in 2008, Vietnam’s Highlands Coffee cafes in 2012, and US chains Smashburger and Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

The group today runs restaurants in 34 territories, with its acquired businesses contributing 42 per cent of the total sales, according to its 2020 financial statement released this year in April.

Jollibee was not an overnight success. Our entire family had to work very hard

But success can be fleeting and difficult, as Tan warned graduates back in 2019.

“Contrary to what some may think, Jollibee was not an overnight success. Our entire family had to work very hard,” he said.

The son of an immigrant cook from Fujian province advised the graduates to “find joy in the actual journey itself” and let failure be their “best teacher”.

In its 43 years of existence, Jollibee has managed to grow a large and diverse customer base, many of whom have since moved abroad. Wherever they went, Jollibee followed.

The diaspora of 10 million Filipinos now living or working overseas, based on statistics from the International Organization for Migration, has contributed to the company’s rapid expansion.

But reaching out to overseas Filipinos was a lesson Jollibee learned along the way.

Tan’s first international foray in opening two joint-venture stores in Taiwan in 1986 proved to be a bust.

According to a source who used to be a mid-level manager in the Taiwan operations, the company struggled to recruit workers due to an uncompetitive benefits package, and the rental doubled to a point that it was no longer viable for the business to continue operating.

“It was actually the wrong timing,” said the source, who now lives in Taiwan. Jollibee arrived “before all the foreign workers came to Taiwan in 1993”, when the island’s government eased restrictions on foreign hires, so it had no Filipino customer base.

While Taiwanese customers liked the chain’s signature fried chicken, or “Chickenjoy”, they did not take to the accompanying gravy, the source said.

The Taiwanese were also not used to sweet spaghetti – another of Jollibee’s top sellers in the Philippines – because “here, the tomato sauce is more tarty”, the former manager added.

Jollibee also used to have two stores in Indonesia in the 1990s, but both have long since shut. A Filipino teacher in Indonesia, who wanted to be known by his first name Floro, said he had to fly to Singapore to get his Jollibee fix.

“Indonesians love spicy food,” he told This Week in Asia. “They also don’t know gravy. They find our Jollibee rather boring.”

COVID-19 IMPACT

Before the coronavirus pandemic swept the world, JFC Group had been seeking to open new stores, including plans to enter Australia and Japan.

But the economic impact of the pandemic made 2020 a write-off for the group, which declared a net loss of 11.49 billion pesos (US$240 million), suspended 8 billion pesos’ worth of capital expenditure; and shut 486 stores, ending the year with 5,824 local and foreign stores.

“In China, the epicentre of the epidemic and which accounts for 6.1 per cent of JFC’s global storewide sales, the decline in sales was abrupt,” the group said in its 2020 annual report. “All the 14 restaurant outlets of Yonghe King brand in and near Wuhan, believed to be the origin of the epidemic, were temporarily closed.”

Philippines’ Jollibee loses US$2 billion on America gamble

The news was just as grim in North America, where Smashburger had to suspend all dine-in operations and rely on takeaway or delivery services.

Recently, an incident occurred which could have further hurt Jollibee sales and the integrity of its brand.

Alique Perez said in a Facebook post on June 2 that she had chicken delivered for her son, only to find a rag caught in it.

“While I was trying to get him a bite, I found it super hard to even slice. Tried opening it up with my hands and to my surprise [found] a deep-fried towel,” she wrote. “This is really disturbing … How the hell do you get the towel in the batter and even fry it!?”

The video she shared was viewed 2.7 million times. Jollibee expressed deep concern and said it had briefly shut the offending branch in upscale Bonifacio Global City in Metro Manila to investigate the failure in procedure and retrain staff.

While the incident went viral, it demonstrated the depth of customer loyalty, with many netizens describing the incident as an act of sabotage, not negligence.

“Jollibee is getting all those lovely support memes … proof that the bee is tops in the hearts of many Pinoys,” one local schoolteacher wrote on Twitter, using a colloquial term that refers to Filipinos.

Jonathan Ravelas, chief market strategist of BDO Unibank, the country’s largest bank, said he remained optimistic about the outlook for Jollibee even amid the Covid-19 slump.

As more people become vaccinated and infections fall, “recovery of consumer income and spending will improve JFC’s bottom line”, he said.

Ravelas described the company as “a good investment for the long term. They are diversifying their food assets around the world”.

On May 21, a Jollibee branch opened at London’s West End. According to Tan’s CEO brother Ernesto, 450 more will open worldwide this year, including at New York’s Times Square.

The jolly bee mascot is also becoming famous. On Monday, popular British comedian John Oliver called it “the world’s greatest fast-food mascot” because “it can promise you happiness” with its risqué dance moves.

Meanwhile, the sizeable Filipino diaspora plays a key role in expanding Jollibee’s customer base by bringing their children and non-Filipino friends to the store.

Genevie, based in Dubai, said her “half-Pinoy, half-Scottish” son had taken to eating its chicken tenders, or crunchy chicken strips.

Domini Comia, a tax consultant in Doha, Qatar, said she had seen Arab children “eating Jollibee with their Filipino yayas (carers)”, while their parents ate something else.

Antoniette Gacad, a paralegal in Daly City, California, said she had observed Chinese nationals, Latinos and Pacific Islanders flocking to the branch there. “Jollibee has not shown any signs of slowing down, because they just opened in another location here in Daly City,” she said.

Meet billionaire Tony Tan Caktiong, the ‘chickenjoy’ entrepreneur

In Canada, Francesca Domingo patronises the lone Jollibee outlet in Calgary, Alberta, “because it’s one of the few Filipino establishments we have in the city”.

“The taste is nostalgic and there’s a sense of community when you enter the restaurant, pre-Covid,” she said. “My niece who is four years old has never been to the Philippines and eating Jollibee is part of her ‘Filipino culture’ experience.”

Ravelas said Jollibee would continue to grow “as long as there are children and those Filipinos who are away from home”.

“A visit to Jollibee will bring them home and remember the good old days, especially during challenging times,” he said.