Explainer | How did migrant worker dormitories become Singapore’s biggest coronavirus cluster?

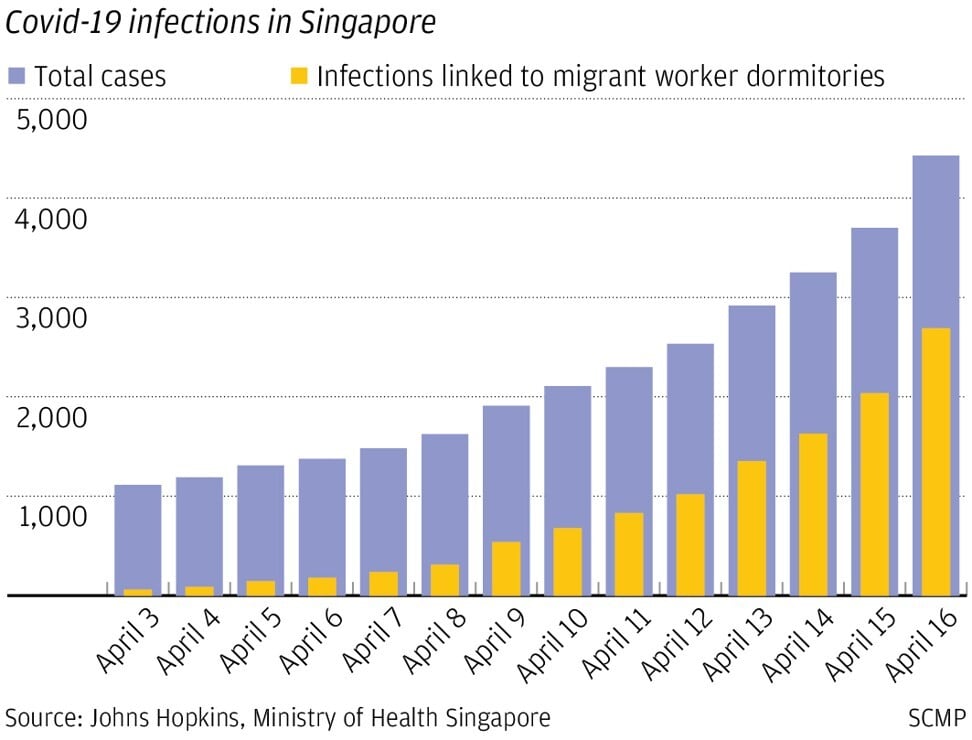

- Cases in the island nation have more than quadrupled in the past two weeks, propelled by a surge in infections among migrant workers

- The government has upped its efforts amid criticism, with former diplomat Bilahari Kausikan saying ‘we did drop the ball on foreign workers’

Who are Singapore’s migrant workers, and why are so many infected?

There are 323,000 low-wage migrant workers in the country, who take on jobs shunned by Singaporeans in industries such as construction, estate maintenance and manufacturing. Their accommodation includes 43 mega-dormitories with more than 1,000 workers each, some 1,200 factory-converted dormitories which typically house 50 to 100 workers each, and temporary living quarters with around 40 workers on various construction sites.

The first infected migrant worker infection was reported on February 8, when a 39-year-old Bangladeshi man working at the Seletar Aerospace Heights construction site caught the disease. He had visited Mustafa Centre – a 24-hour shopping centre – before he was hospitalised, and stayed at The Leo dormitory. The Seletar Aerospace Heights work site eventually became a cluster with five infections, but it was contained and only towards the end of March were migrant workers again reporting infections.

Singapore’s boomers haven’t gone mad, they just need time to process coronavirus measures

The first dormitory cluster was identified on March 30, with four infections at S11 dormitory. Cases among workers living in dormitories quickly ballooned to 2,689 – representing 60 per cent of all cases in Singapore – of which 979 came from the S11 dorm.

The surge has changed Singapore’s transmission rate (Ro) – the number of newly infected people from a single case – from “well under one” before the outbreaks in dormitories to “somewhere closer” to one, said director of medical services Kenneth Mak.

Manpower minister Josephine Teo attributed this rapid spread to workers socialising across dormitories on their days off, then again with different groups of friends within their dormitories. “They might, you know, cook together, eat together. Relax together,” Teo said. Authorities have identified the 400,000 sq ft Mustafa Centre – popular with migrant workers, locals and tourists – as a starting point for the disease’s spread among workers.

How did this happen when Singapore seemed to be successfully flattening the curve?

Singapore reported its first Covid-19 infection on January 23, but seemed to be successfully containing the disease, with just 102 cases as of February 29. That quickly ballooned to 1,000 by April 1 as soaring infection rates worldwide prompted overseas-based residents of the city state to return home – some of whom were carrying the disease, sparking a second wave of infections through imported cases.

As the country focused on this rise in imported cases, it missed the infections happening among migrant workers. National development minister Lawrence Wong said many of the workers had continued working as their symptoms were mild. “We did drop the ball on foreign workers,” wrote former Singapore diplomat Bilahari Kausikan, an active commentator on social media.

The fundamental issue is the poor living conditions faced by these men. They sleep on bunk beds, 12 to 20 people packed into a room ventilated by small fans attached to the ceiling or walls. Hundreds of men on each floor share communal toilets and showering facilities.

Coronavirus: Indian superstar Rajinikanth offers supportive words to Singapore’s quarantined workers

As early as March 23, non-profit Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) had written to local media that these conditions were ripe for a Covid-19 cluster. On top of this, workers are transported squeezed into the back of a truck, and not showing up for work leads to a fine – so many of them work despite being ill.

“We at TWC2 knew it was only a matter of time before Covid-19 would begin to spread in worker dormitories, where conditions are nearly ideal for transmission of infection,” the organisation said on April 3. “It gives us no pleasure to be proven right so soon after.”

Who runs or owns the dormitories in which migrant workers live?

The 43 mega-dormitories that house 200,000 workers are operated by the likes of offshore and marine company Keppel and real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield, as well as listed companies such as Centurion, which also operates student hostels and workers’ accommodation in Malaysia and Australia.

They charge construction companies who hire the workers S$300 to S$400 (US$210-US$280) per worker for lodging each month, while workers pay around S$130 a month for three catered meals a day. Efforts to contact the operator of the S11 dormitory – which has the largest cluster of infections in Singapore – were not successful, but owner Jonathan Cheah in 2015 told local media his second dormitory, Changi Lodge 2, had an annual turnover of S$15 million and S11, if full, could hit an annual turnover of S$55 million.

Singapore makes face masks compulsory as coronavirus infections surge

What is being done about the situation now?

Manpower minister Josephine Teo on Thursday said the city state would adopt a three-pronged strategy. “With the number of cases at the dormitories continuing to rise, our immediate priority for the workers in the dormitories is to help them stay healthy and minimise the number that gets infected,” she wrote on Facebook.

This would include locking down dormitories with known clusters of infections, she said, meaning that there was “no more going in and out”. Twelve of the 43 registered dormitories are currently gazetted as isolation zones, with workers staying in their rooms as much as possible and meals sent to them. The government is also testing several thousand workers a day to identify and then isolate those infected.

The second measure is to prevent clusters from forming at other dormitories, Teo said, explaining that this would be done by isolating those who had tested positive for the virus and their close contacts. Even though not all dormitories have known clusters, authorities aim to apply the same measures across the board, with social distancing measures strictly enforced and no “free mixing” among workers.

The third approach involves relocating about 7,000 workers who are well and are in essential services, Teo added. These workers were moved to separate facilities including military camps, exhibition centres, floating hotels, and empty housing blocks.

Coronavirus: Singapore migrant worker dormitories still hot topic as Covid-19 cases rise

What’s the situation in the dorms now, and how do migrant workers feel?

Local media reports have previously highlighted poor living conditions in some dormitories, ranging from kitchens infested with cockroaches to overflowing urinals, but the manpower ministry has over the past weeks said living conditions have improved.

Cleaning, waste management and sanitation efforts have been ramped up, and a dedicated team comprising 380 to 400 personnel from the Singapore Armed Forces and the Singapore Police Force has been deployed to work with dormitory operators to ensure timely food delivery. Medical posts have also been set up at dormitories to look after workers who exhibit symptoms.

Still, Bangladeshi workers who were interviewed by local media have expressed their fears about the virus as more dormitories were hit. One of the interviewees said they were now unable to go to other workers’ rooms or other floors within the dormitories, and most of them were either on their phones with loved ones or reading books.

How have Singaporeans reacted?

The drastic spike in cases among migrant workers has led to some xenophobic comments online, including a letter published by Chinese daily Lianhe Zaobao on April 13.

The letter, written by a reader, urged citizens not to blame the Singapore government entirely for the worsening situation, adding that migrant workers should take responsibility for their poor personal hygiene.

Even though some netizens agreed with the points raised, others criticised the writer’s remarks and said they were a reflection of how poorly most Singaporeans treated migrant workers – even though they were a vital part of Singapore’s growth and economic boom.

Human rights activist Kirsten Han wrote in a recent commentary: “Singapore’s government is often praised, domestically and internationally, for its planning and foresight … but recent developments have demonstrated that you can’t have foresight for things you refuse to see.”

Singapore’s Ho Ching thanks ‘friends in Taiwan’ after quibble over masks donation

The opposition Singapore Democratic Party also weighed in, with leader Chee Soon Juan in a Facebook video pointing out that national development minister Wong had visited the dormitories in early February with manpower minister Teo, saying at the time that there would be tighter monitoring of workers.

“If there was really tighter monitoring and enforcement, why did they also not ensure that steps were taken to prevent the situation from deteriorating? Warning signs were flashing,” Chee said.

Meanwhile, migrant groups have sprung into action to help the workers in lockdown, and a swell of community initiatives have helped pool resources to donate food, masks and money to them.

Others have started volunteering as interpreters to assist doctors attending to Bangladeshi patients, with one graduate from the National University of Singapore, Sudesna Roy Chowdhury, later building a translation portal for medical teams treating migrant workers.