Explainer | Why is Singapore giving 20,000 blood oxygen monitors to migrant workers?

- About 8,000 pulse oximeters have already been given to workers with Covid-19 and another 12,000 will be distributed to those living in dorms

- The devices, usually used to monitor asthma and pneumonia patients, can help identify those who have coronavirus before they exhibit symptoms

Yet many of these workers exhibit few, if any, of the symptoms usually associated with the respiratory disease, according to authorities – which is why thousands of medical devices known as pulse oximeters are now being distributed, to help detect the early warning signs of a coronavirus-related deterioration in health.

How did migrant worker dorms become Singapore’s biggest coronavirus cluster?

Some 8,000 pulse oximeters have already been handed out to migrant workers with Covid-19 and another 12,000 will go to those living in dorms. But what is this device that has been touted by health care experts around the world as a useful tool in the fight against coronavirus?

What is a pulse oximeter?

A pulse oximeter provides a non-invasive and painless way to measure how much oxygen is being carried in a person’s blood. It consists of a light-emitting sensor – most commonly clipped on to the tip of a finger – that can determine oxygen saturation levels within seconds by measuring changes in the wavelengths of light as it passes through the body. Typically, the device is used to monitor patients with asthma, pneumonia, lung cancer and other respiratory ailments.

Invented in the early 1970s by Japanese bioengineers Takuo Aoyagi – who died in April aged 84 – and Michio Kishi, the device was commercialised by American medical technology company Biox in 1980 and is now in use in health care settings around the world.

How does it help with Covid-19?

Some coronavirus patients have been developing dangerously low levels of oxygen in their blood long before they start to feel any shortness of breath – a condition known as ‘silent hypoxia’.

This can result in patients who exhibit no outward signs of respiratory distress being admitted to hospital with undetected rampant pneumonia and blood oxygen levels so low that they should be unconscious.

But a pulse oximeter can help detect this drop in oxygen levels and catch the disease at an early stage, before it progresses from pneumonia to acute respiratory distress syndrome, which almost always requires mechanical ventilation.

New York City officials have said at least 80 per cent of Covid-19 patients who were on ventilators at the height of the city’s outbreak died, while survivors can walk away with long-term physical and psychological damage – showing the importance of early intervention.

Pulse oximeters are not perfect, however. They sometimes give false readings, can provide “inappropriate reassurance for both clinicians and patients” and encourage “inappropriate overreliance on a single number rather than complete assessment of the patient”, Dr Pieter Cohen, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, wrote in a letter to The New York Times.

How will they be used in Singapore?

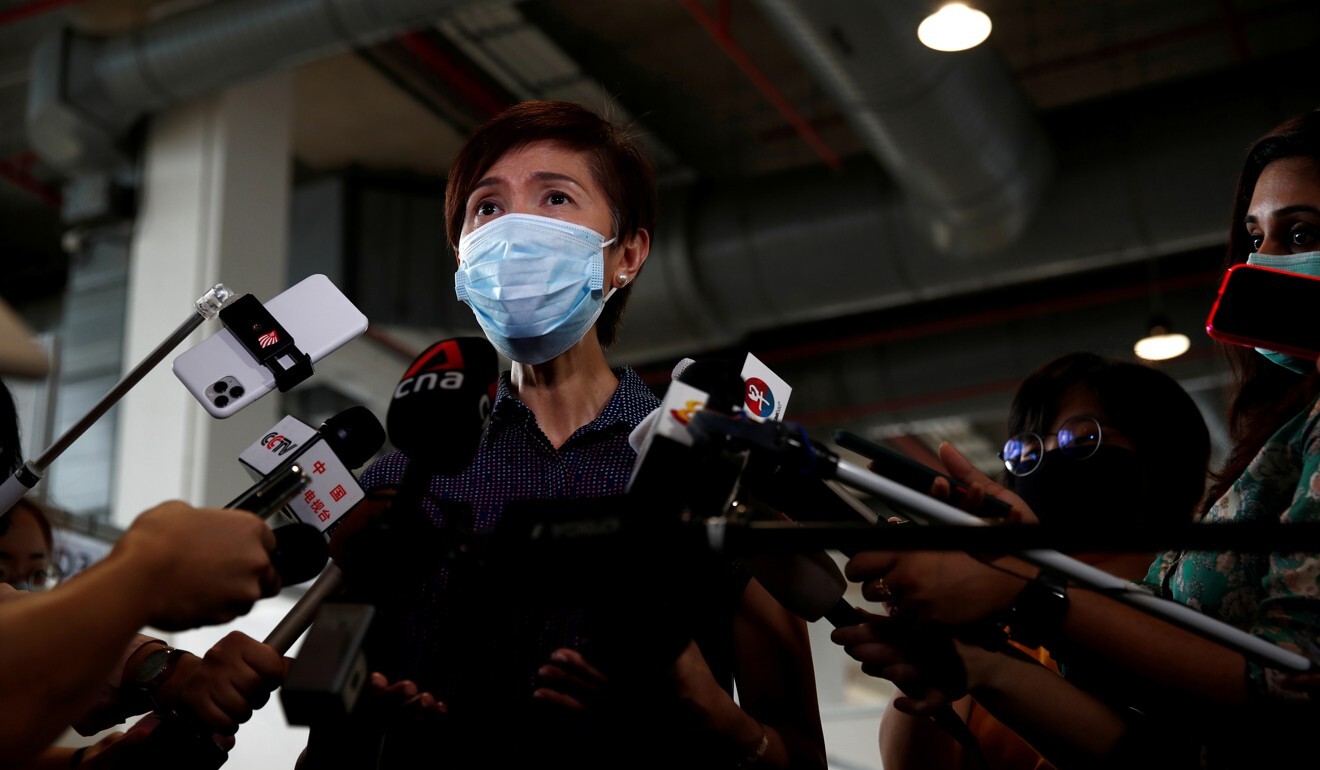

Because most migrant workers who catch coronavirus are asymptomatic, or exhibit only very mild symptoms, they may not know they have Covid-19 until it is too late, according to Manpower Minister Josephine Teo.

“As a result, even if they have already been infected, or they are still infectious and passing the virus to somebody else, they don’t know it,” she said while announcing the new distribution policy, adding that pulse oximeters can help the ministry conduct “health surveillance … in a more comprehensive way”.

The rates of infection in some of Singapore’s migrant workers’ dorms are so high that the authorities have stopped immediately testing those who have respiratory symptoms – opting instead to isolate and treat patients within their dorms first before eventually testing them.

And while pulse oximeters can theoretically help with identifying new cases, Singapore infectious disease specialist Leong Hoe Nam questioned their usefulness with regards to migrant workers.

“The risk of them developing pneumonia and needing oxygen is slim,” he said, citing most workers’ relative youth as a factor. “But for the patient, it appears that something is being done. It has a therapeutic effect.”

Distributing the devices will also relieve some of the pressure on Singapore’s health care system, Leong said, by making migrant workers less reliant on in-person visits by health care workers.

“It is a win-win situation because the pulse oximeter is cheaper than deploying staff there to check on individuals,” he said.

Where else are they being used?

About 5 per cent of these patients later developed pneumonia, “but they detected it early with the oximeters … they all got treated early and they all did well and they all avoided a ventilator,” Dr Richard Levitan, an early proponent of the devices who volunteered at a New York City hospital for 10 days in March, said in an interview with CGTN Europe.

As early as March, the WHO told countries to “optimise the availability of pulse oximeters and medical oxygen systems”.

What other measures has Singapore introduced?

Eight interactive kiosks have been installed in migrant workers’ dormitories, offering round-the-clock doctors’ consultations even after the on-site medical teams have left for the day. These kiosks are connected to devices which can monitor patients’ vital signs, such as blood pressure and temperature.

All migrant workers are also able to have a virtual consultation with a doctor via their personal mobile phones. About 400 of these video consultations have been carried out since the service started on April 25.

Meanwhile in Changi Exhibition Centre, which has been converted into an isolation facility for Covid-19 patients with mild symptoms, five robots have been deployed to deliver food and reduce the number of staff members needed in areas housing infected patients. There are also blood pressure machines and pulse oximeters for patients to conduct their own health checks three times a day.

Additional reporting by Reuters

Help us understand what you are interested in so that we can improve SCMP and provide a better experience for you. We would like to invite you to take this five-minute survey on how you engage with SCMP and the news.