- Hundreds of posts on Telegram and other apps show non-consensual content being shared and even sold, while advocates and survivors say too little is being done to stop it

- As similar groups proliferate in countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea, some women – and a few men – have decided to take action

This is the second in a series of stories on image-based abuse supported by the Judith Neilson Institute’s Asian Stories project, in collaboration with The Korea Times, Indonesia’s Tempo magazine, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, and Manila-based ABS-CBN. Sonia Sarkar, Tashny Sukumaran and Lee Min-young contributed reporting. The piece contains descriptions of a sexual nature. This story has been made freely available as a public service to our readers. Please consider supporting SCMP’s journalism by subscribing.

Amala*, 22, from Malaysia, recalls the day it felt like her mobile phone would never stop lighting up with Instagram follow requests from men.

“My stomach instantly dropped when I realised what was going on,” she said. A male friend later told her that her Instagram posts and username had been shared with some 40,000 members of the Telegram channel V2K.

“I felt nauseated and pretty much clueless, like every other person who has been in this situation,” Amala said.

V2K – which was last year denounced by women on social media, who also reported it to the Malaysian authorities – is one of hundreds of groups that have sprung up on chat apps such as Telegram.

The encrypted messaging platform, which has half a billion users, gained popularity amid a drive to protect user data from governments – but it has also come under increasing scrutiny for being used to share illegal and abusive content.

[Part One] Porn, privacy, and pain: how image-based abuse tears women's lives apart

[Part Three] For lust and money: when online sexual encounters end in despair and death

This Week in Asia analysed hundreds of posts on Telegram groups, where images of children as well as non-consensual content involving women have proliferated, while also looking into cases of pictures and videos shared by schoolboys on social networks such as Instagram.

Faced with a slow response from the platforms and the police, some women – and a few men – are taking the issue into their own hands by infiltrating these groups and assisting the authorities in their investigations.

CHILD ABUSE

Set up by self-exiled Russian brothers Pavel and Nikolai Durov in 2013, Telegram allows users to exchange messages and reach a wide audience through groups called “channels”. It has become the app of choice for protest movements in places such as Hong Kong, where activists and others use it to organise demonstrations and share news while avoiding censorship and ensuring privacy.

However, Telegram has also been criticised for allowing the proliferation of malicious activity such as terrorism, rampant misogyny, and other forms of abuse in its chat rooms.

Two Italian scholars, Silvia Semenzin and Lucia Bainotti, found that the sense of anonymity provided by the platform, its weak regulation, and the ability to create large male communities had contributed “to the reinstatement of hegemonic masculinity”.

This Week in Asia reviewed more than 20 channels – some of them extremely graphic and involving the online sexual exploitation of children. Many of these groups can easily be found by searching keywords on the Telegram app as well as through invitation links, and their content can often be accessed without even having to join the groups.

These channels not only re-shared screenshots of photos and videos from social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, but also nude pictures and messages that had been sent privately; home-made sex videos, some of which were taken without consent; and photos of sleeping women.

The personal information of women and girls – including their social media handles, phone numbers, and even home addresses – had also been published.

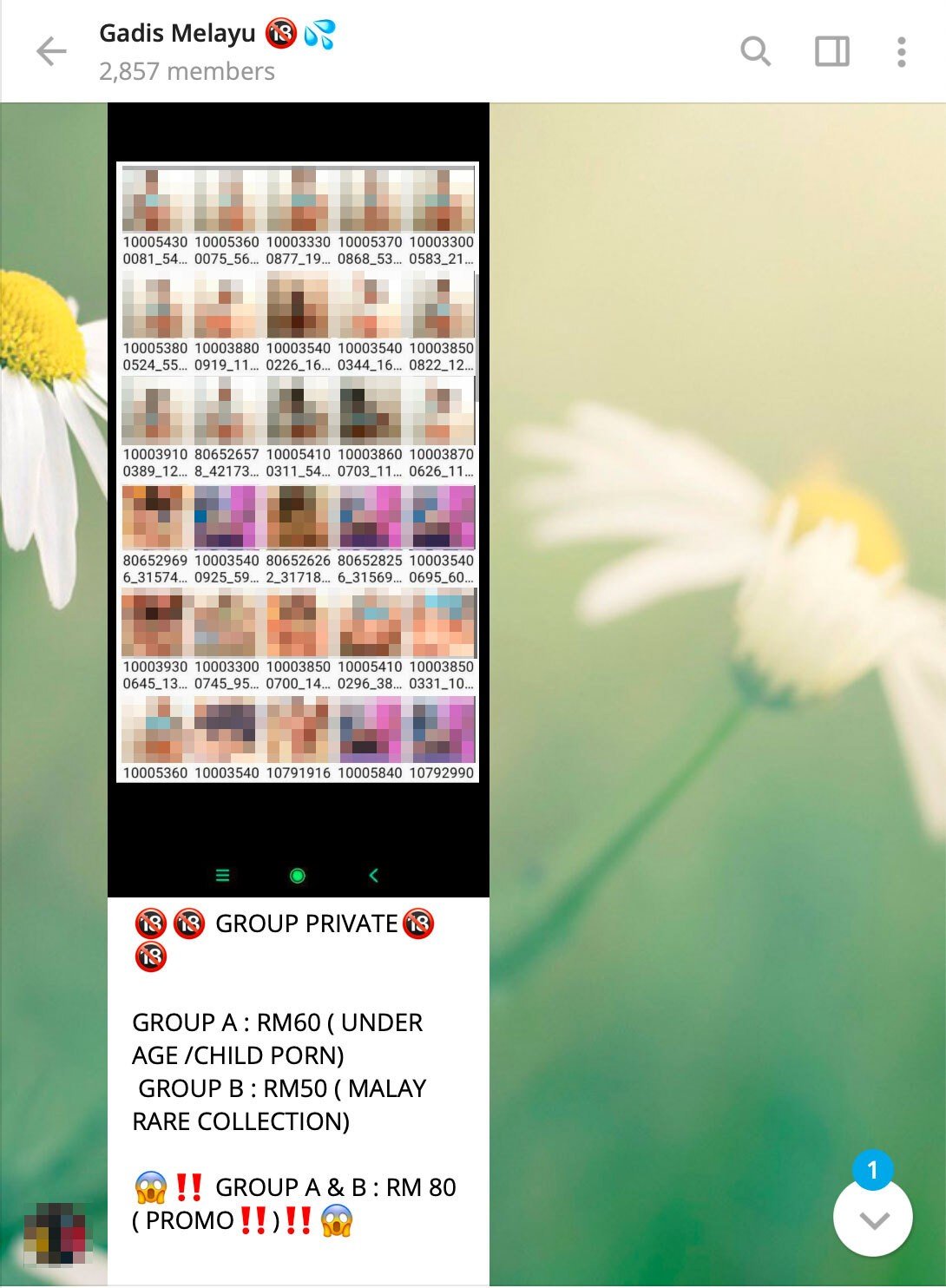

In a Telegram channel named “Gadis Melayu” – or “Malay Girl” – we found dozens of posts with pictures of children’s faces and bodies, as well as images of women that appeared to have been posted without their consent. By early June the channel – identified in the invite link as “melayutop” – had more than 2,800 members, and displayed more than 1,500 photos and 915 videos.

Several posts showed screenshots of entire galleries of images and videos involving children, with one of the holders of this illegal content described as a“trusted dealer”. At least 20 other posts were even more graphic, showing girls and boys engaging in sexual acts with adults.

Bahasa Malaysia was often used in chats and some payments were requested in ringgit, though Indonesian children were specifically mentioned in the written description of at least two of the messages we reviewed.

We reported the channel to Telegram for child abuse on May 7, but no action had been taken as of publication time. In fact, more posts with such content have been shared in recent weeks.

On May 11, for instance, another collection of photos and videos of children was promoted in the channel, with prices and contacts for those who wanted access to it. The same day, a video of an Asian girl exposing her genitals was posted in the group.

More recently, another user wrote: “I just want links to sex videos of little boys and girls.” There were also messages that referred to a “pedomom” – an allusion to a mother’s involvement in pedophilic content.

In countries such as the Philippines, where millions of families lost their income during the Covid-19 pandemic, more parents are turning to selling their children online for sexual exploitation.

We also filed a report to the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), which is responsible for finding and removing images and videos of child sexual abuse from the internet. Its response was swift, but its hands were tied.

“We are aware of many file sharing programmes available and that they are open to abuse,” the Britain-based charity wrote in a May 13 email, four days after our report.

“The services are based on a peer-to-peer system, without any ISP-hosted content,” the IWF added, referring to internet service providers in a specific geographic location. The foundation does not have the authority to investigate individual internet users and the content of their hard drives.

“This is currently under the sole remit of the police,” it said. “We can only investigate content that is hosted in the public domain.”

Nevertheless, the IWF processed a record 299,600 reports of child sexual abuse imagery last year, including tipoffs from members of the public – close to 40,000 more reports than in 2019.

The charity has also seen a staggering 77 per cent increase in the amount of “self-generated” abuse material, as more children and criminals spend longer online amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

Content of this nature includes child sexual abuse captured by webcams, often in the child’s own room. In some instances, the foundation said, children are groomed, deceived or extorted into producing and sharing a sexual image or video of themselves.

Experts note that there is still limited research on child online safety in the Asia-Pacific region, with many countries still failing to provide sex education.

UNDER THE RADAR

While some Telegram channels are more focused on explicit content, others share images portraying women in everyday situations such as having fun with their friends at beaches or swimming pools, and working out at the gym – albeit often without their knowledge and consent.

In a group named “SG Sports Bra Babes”, a post read: “Hi everyone, if you’re going to submit pics, please crop out the Instagram slide numbers or tagged icon. You can wait for about two seconds before screenshotting and the icons will fade away.”

This suggests that the photos – and some videos – are screenshots from social media accounts, rather than being shared by the women themselves. The channel, which was set up in February, had 179 subscribers at the end of last month, but some posts had more than 1,000 views.

In another message from March, the administrator decided to run an anonymous poll, which asked users: “Planning on starting a SG Bikini Channel, anyone up?”

On a channel called “Mysggirls”, with more than 4,000 subscribers, there were photos and videos of girls, including some in school uniform. Upskirting videos had also been uploaded, and the administrator wrote in January that people who felt offended should leave the group rather than reporting it.

Those who set up such channels on Telegram, and many of their members, are often aware they are being monitored. Some even teach subscribers how to evade authorities and activists.

In a private group called “Love United”, which is believed to be based in Singapore, an active user with the handle “Just Siew Mai” warned others about the risks in late March.

“Stay here but keep no traces of your online identity. Change your DP [profile picture], your username and most importantly, don’t get too attached to your Telegram stuff. Be ready to delete your Telegram account at a moment’s notice. That’s how we combat those white knights,” the user said. “What we are doing is lawfully wrong already, so we must do it smartly in order not to get caught.”

Just Siew Mai also told others not to worry if activists had exposed the group on Twitter, adding: “Make sure your online identity and character is totally different from your real life persona.”

The user later deleted these messages.

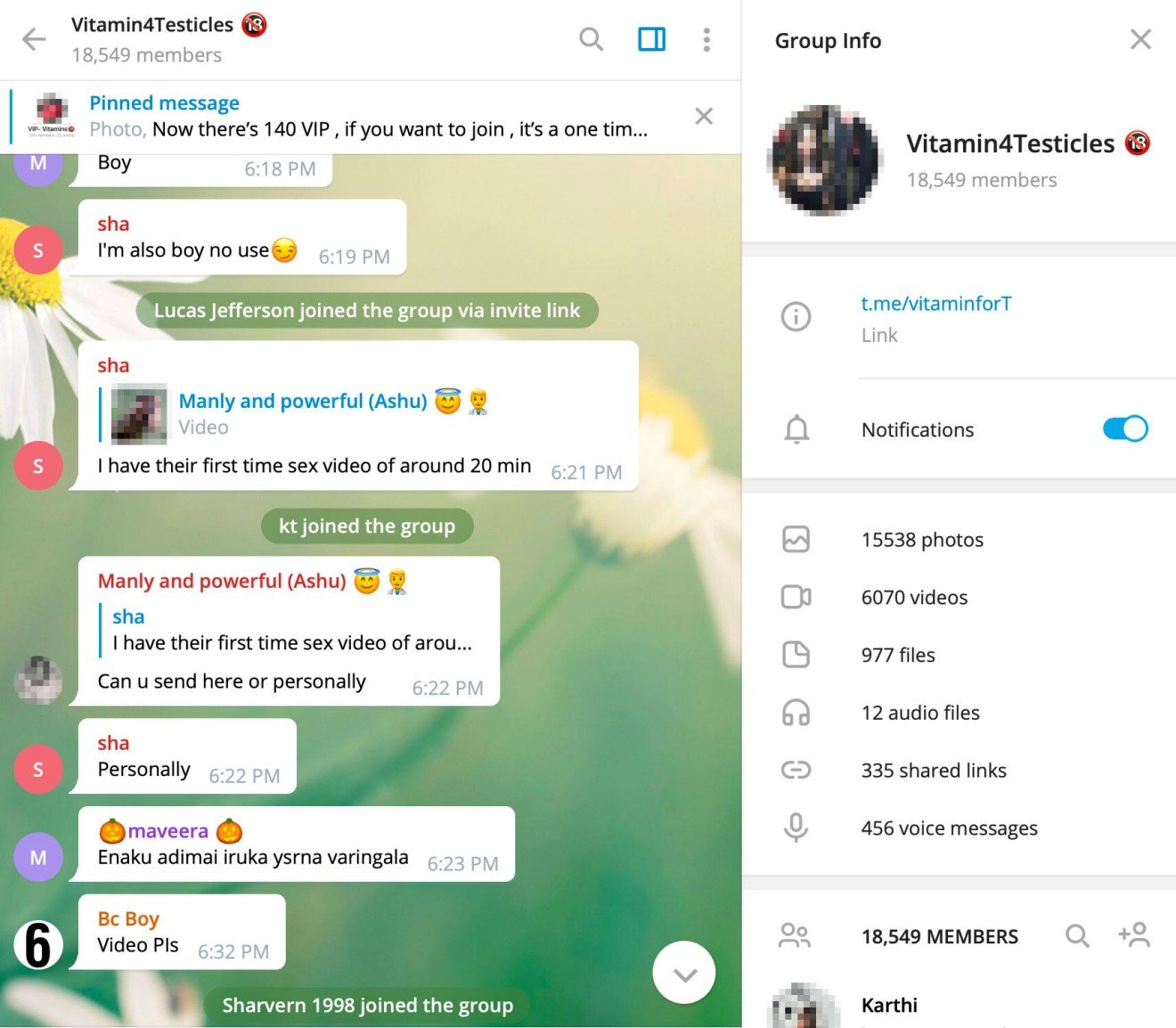

On “Vitamin4Testicles” – a channel in which more than 19,000 members shared over 15,000 photos and 6,000 videos, mostly of women from Malaysia – there were frequent requests for leaks about specific women. Some also openly offered and sold images of their ex-girlfriends.

“If your friend’s photo is in [the] group then it’s already with many people,” a user wrote on May 13. “Something [that] is online is always online. You are here to watch nudes, just accept it.”

There are even users who warned others not to post content about a specific woman after realising she had filed a police report.

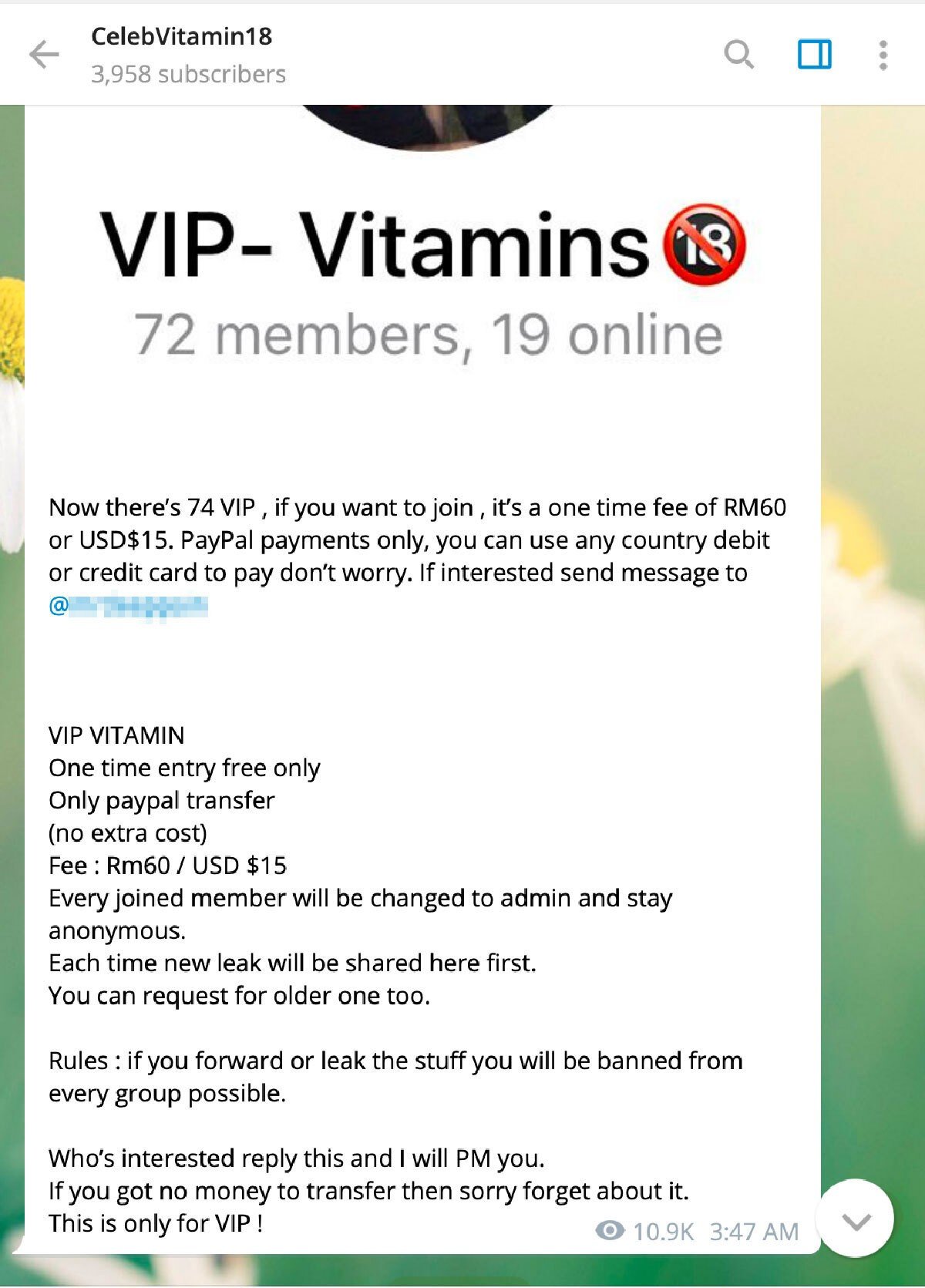

While some channels are public, other rooms are private – and access to those has varying requirements, including payments in cryptocurrency, or photos of the users’ genitals and faces.

Telegram seems to be actively preventing users from accessing some of these groups, but only through iPhones. For instance, when we tried to join “Sg Nasi Lemak Official”, a Singapore-based channel created on November 26, a warning appeared on an iPhone: “This channel can’t be displayed because it was used to spread pornographic content.”

But the group, which has more than 5,000 subscribers, was still accessible on Android devices – which have Google-developed operating systems – and Telegram’s Mac application.

“If you download the app directly from the Internet [instead of through] the App Store, you are still able to see banned conversations which are hidden on iPhones. Interestingly, the only reason Telegram bans this kind of group is because they do not want to be removed from the App Store – which criminalises pornographic content,” said Italian researcher Semenzin, a lecturer in new media and digital culture at the University of Amsterdam.

David Thiel, Big Data Architect and Chief Technology Officer of the Stanford Internet Observatory, said despite the public’s general impression, “Telegram is not, broadly speaking, an encrypted messaging app”.

“Group chats are unencrypted, and one-to-one chats are unencrypted by default,” he said, adding that this meant “Telegram has access to the content of the chat, so it could be identifying adult content itself, or relying on user reports against particular groups”.

Thiel, who previously worked for Facebook, said rather than companies such as Apple pushing apps on its platform to crack down on this content, a better solution would be Telegram implementing controls on material showing the sexual abuse of children as well as non-consensual intimate imagery across all platforms.

“I personally think this should be a cross-industry collaborative effort,” he said.

Apple and Google did not respond to questions from This Week in Asia.

One of the most surprising things about the Sg Nasi Lemak Official channel – also known as “Sg Nsl Official” – is that it resembles another group that was previously investigated by the Singaporean authorities.

In October 2019, four men were arrested and later pleaded guilty for their involvement in the channel “SG Nasi Lemak”, which mainly displayed videos and pictures of Singaporean women to its 44,000 members.

The channel’s 39-year-old co-administrator was this year sentenced to nine weeks’ jail as well as a fine of S$26,000 (US$19,550). Two others, aged 20 and 18, were placed on probation for distributing obscene material, while a 27-year-old man, another administrator, was sentenced to a year of mandatory psychiatric treatment.

But these penalties do not seem to have served as a deterrent to those operating and sharing this content.

The new Sg Nasi Lemak Official channel was recently used to promote “premium content” in a separate group, subscriptions for which varied from S$88 for a month to S$850 for a year. The payments, they said, should be made using bitcoin.

The teasers clearly stated that at least part of the shared content was non-consensual. Several posts promised there would be new videos released daily and that private information – such as Instagram accounts and names – would be leaked.

LENDING AN EAR

Nisha Rai, a 21-year-old university student from Singapore, in March joined about 20 young women and men who monitor online chat rooms for illegal and non-consensual content. She now spends most of her spare time reaching out to girls and women who have had their images or videos leaked, while compiling lists of these groups’ administrators and active members.

Over the past three months, she has sifted through some 70 channels and contacted dozens of women.

“What we do on our end is to encourage [survivors] to lodge a police report, especially if they know who they sent [pictures] to or if they know who’s the one who leaked the videos,” Rai said.

But more than anything else, she said, her group existed to lend an ear to those affected. “Sometimes you just want to know that somebody’s there … We can talk to them and direct them to other organisations that can provide them with professional help should they need it,” she said, noting that the members of her group did not have formal training in this regard.

Rai said the non-consensual sharing of images had become “a huge concern” for young women such as her.

“I am someone who is an avid user of social media … At times, when I get an influx of messages or a sudden surge of follower requests on Instagram, I start to wonder if someone had screenshotted my picture and sent it out in the groups,” she said.

Rai, who has also helped launch an Instagram support page for survivors, worries about the different forms of harassment and trauma that can be caused by image-based abuse. “At the end of the day, when such images get shared and sent out, our physical and online safety is immediately at risk,” she said.

Some men are also lending a hand in the fight. Raakesh Sivapalan, 23, a material handler at a company in Singapore, joined Rai’s team this year after a conversation with his fiancée about such Telegram groups.

Sivapalan said he had helped by compiling resources available to survivors and offering advice on how to navigate the Singaporean legal system.

He is currently undercover in about five groups – some with 3,000 to 4,000 members – to collect information.

“I am not only frustrated, I am also very angry. As a man, I feel that this is so wrong,” he said, referring to those who shared photos of women without their consent. “If someone breaks up with you, you must show character and dignity instead of chasing the girl in this way.”

He said he had encountered men seeking to embarrass former partners, but there were also men who turned to these groups for personal pleasure. “It’s content that is easily available,” he said.

Sivapalan, who witnessed a case of intimate image abuse in his personal circle, said he had come across too many upsetting posts – some of them involving children. He is now focused on understanding how transactions of this sort of content take place, and whenever possible he takes the cases to the authorities.

“I feel like I need to stand up, as a man,” he said. “These men need to understand that women shouldn’t be treated this way. They should think that they too can be affected, their sisters, their cousins … they too can be targets.”

A study focused on Australia, New Zealand and Britain, published last year, found that one in five men had reported having engaged in one or more forms of image-based abuse.

Those who shared and/or threatened to share nude or sexual images – most commonly men under 40 years old – said they had done it mostly for fun, and to flirt or be sexy. According to the study – which was conducted by four scholars, including Anastasia Powell, lecturer in justice and legal studies at RMIT University in Australia – their other motivations included wanting to impress friends, for financial gain, to obtain more images, or for revenge on or to control a former partner.

“These findings show a range of diverse motivations for engaging in image-based sexual abuse,” the study said. “In some cases, perpetrators reported motivations which appeared to be less about personally targeting a specific victim and more about their own capacity to either make money or gain status.”

The report also suggested that those engaging in these behaviours might not fully understand or even give much thought to the potential impact on survivors. “Importantly, there appears to be a tendency among perpetrators not to recognise image-based sexual abuse as harmful,” the study said.

Shailey Hingorani, head of research and advocacy for the Singapore-based non-profit Aware, said “for the sake of a perpetrator’s momentary pleasure or spite, a survivor may live with anxiety for the rest of her life”.

She pointed out that much like all forms of gender-based abuse, tech-facilitated sexual violence was about power and control, and the disregard of women’s consent and agency.

“The ease at which men can now capture, disseminate and watch voyeuristic videos seems to have further normalised the practice, and accelerated the rate at which female bodies are reduced to commodities for male consumption,” Hingorani said, noting that perpetrators were rarely held accountable.

“We even know that men explicitly encourage each other to commit these acts over and over. So it is entirely unsurprising to see our case numbers going up. The trend is likely to continue.”

The government of Singapore earlier this year said it was working to set up a new alliance focused on tackling online harms, especially those targeting women. It also said new laws could be introduced to tackle issues that included the dissemination of voyeuristic material and non-consensual intimate images.

RAPE CULTURE

However, there is a widespread belief that policies and laws have been too slow in catching up with perpetrators and the growth of technology. Non-consensual images have ended up not only in mainstream social media and chat apps, but also in more niche messaging platforms such as Discord, which is widely used by gamers.

Against the backdrop of the #MeToo movement, which has seen women around the world push for accountability for sexual misconduct, an increasing number of survivors have come forward.

Soma Sara, who studied in Britain, last year set up a website called Everyone’s Invited, which has turned into part of the movement against rape culture. It has compiled thousands of testimonies from survivors of abuse, including non-consensual sharing of intimate images, many from students who attended private schools in England.

There are accounts of how some students set up groups on social media and chatting apps in which photos of girls were traded. But when these cases were reported to schools, few acted on behalf of the targets and most perpetrators faced few consequences, multiple statements said.

“Boys had group chats where they would ridicule and spread multiple photos of naked girls online. The school found out but barely punished them,” read one testimony, which mentioned a top British school.

In India, the authorities last year cracked down on an Instagram group chat in which 27 teenagers from New Delhi’s top schools shared images of 15 underage girls, along with lewd comments about them. This came after leaked screenshots of the group went viral on platforms such as WhatsApp and Twitter.

Shubham Singh – the founder of Cyber World Academy, a portal that offers online courses in ethical hacking – was one of the first cybercrime experts to come across the private chat, which was called “Bois Locker Room”.

At least two survivors had approached Singh to seek the removal of their images from the group, as they feared that filing police complaints would draw further attention to them.

“One of the victims told me that her image was morphed and shared in the group,” Singh said. “In another case, a male member of the group had shared nude images of his ex-girlfriend, which she had privately shared with him when they were seeing each other. The victim said her ex-boyfriend had already threatened to release these photos on social media when she broke up with him.”

Online violence against women and girls is still not considered as urgent or a big issue, but just a side effect of staying online

During his investigations, Singh discovered other private chat groups with similar content, including one called “Wall of Shame”. He said he encountered at least 30 cases of cyberbullying every day.

“Bullying has always been common among teenagers in physical space. In cyberspace, bullying takes the form of sexual bullying as people think that this is a private group and nobody is watching,” he said, noting that many saw it as a form of entertainment.

A 19-year-old Delhi college student, who claimed he was privy to Bois Locker Room chats through one of its members, said most of the discussions in the group were about sexual expectations that the boys had from girls.

He admitted that some of the members had shared pictures of minors without their consent, and that there were also morphed images of a girl.

“Some of the members objected to it too, my friend told me,” he said, though he maintained that “none of them wanted to rape girls in real life” and that some in the group were only “silent members”.

Anyesh Roy, deputy commissioner of the New Delhi police’s cybercrime unit, who investigated the case, said the group's adult administrator had been arrested and charged, but he was out on bail before the trial. A teenager who was detained had been released last year, he added.

He said devices belonging to members of the group, primarily mobile phones, had been sent to a forensic lab for investigation.

“We are waiting for the forensic results,” Roy said. “Not everyone may have engaged in offensive and unlawful activity in the group … If anything incriminating comes against the other members, we will take action against them.”

‘IT’S NOT JUST SOME LOSERS’

The issue of image-based abuse has become increasingly prominent in South Korea, which has been rocked by a wave of online sexual abuse cases, some involving K-pop stars and actors.

In 2018, tens of thousands of women joined protests in Seoul, holding up signs that read “my life is not your porn” while calling out the watching and taking of non-consensual videos as well as the country’s patriarchal culture.

A number of porn sites and online file-sharing drives have been shut down in South Korea due to public pressure and heightened scrutiny, but encrypted chat rooms with foreign servers have gained popularity as alternatives.

Following a national outcry, South Korean authorities last year took the unusual step of publicly identifying a then 24-year-old as the leader of an online sexual blackmail ring involving Telegram channels. Cho Ju-bin was behind chat rooms that profited from victims, many of them underage girls, by blackmailing them into sharing degrading and violent sexual imagery of themselves.

Cho was sentenced to 45 years in prison, while Moon Hyung-wook, another major player in the case, received a 34-year sentence. Related trials are still ongoing.

Two female university students in South Korea, who call themselves Team Flame, were the first to investigate these groups. Although their work eventually led to police investigations into the case, with users trying to lay low amid a recent spate of arrests, the illegal channels are no closer to disappearing.

“We don’t think it is over because we still monitor the chat rooms, and there are still rooms with thousands or tens of thousands of people, and illegally filmed videos and sexually exploitative content are still shared there,” said Bul*, one of the young journalists. “They say in the rooms, ‘Let’s resume when things get quiet’. So we deeply feel we should keep an eye on them and punish them.”

One still-active channel is dedicated to “acquaintance insulting”. “Perpetrators make composite photos by adding the faces of their classmates or even their families, such as mothers or sisters … to sexual, erotic photos,” said Dan*, the other member of Team Flame.

In addition to morphing the pictures, those in the channel write vulgar and sexually insulting comments under the photos, and even share the personal information of some targets.

Bul and Dan have also monitored Chinese-language groups in which content produced in South Korea and China is shared.

“We are currently in four rooms that use Chinese, and one of them has more than 30,000 members,” Dan said, arguing that China should step up its efforts to tackle online sexual abuse.

Bul said their work had revealed the sheer scale of the issue. “People generally think this is limited only to some losers and it has nothing to do with them. But we learned that so many people around us are exposed to and are engaging in this act of sharing sexually exploitative content.”

In Malaysia, a managing member of the feminist collective CybHer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said those who had gone undercover to investigate these groups faced great risks. But on top of being the targets of doxxing and cyberbullying, she said one of the most difficult things to deal with “was realising that your own boyfriend, father, brother, relatives and friends were in the groups, and most often were sharing pictures – often nudes – of their friends”.

After the Malaysian authorities cracked down on some groups late last year, most of them went quiet, much like in South Korea. But it did not take long before backup groups and new channels sprang up.

This means organisations such as CybHer – which was set up primarily to offer support and help to the affected women – are sorely needed.

“Currently, infiltrating the groups enables us to help our friends and other women who are afraid that their pictures are possibly being shared in these groups,” said the managing member.

There are also reports that images with faces of women superimposed on nude bodies were being widely shared in Telegram channels such as Vitamin4Testicles.

“What we can learn from this is that there needs to be constant monitoring,” said Nicole Jo Pereira, a community development executive with the Make It Right Movement at Brickfields Asia College.

The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission did not respond to queries about investigations into the V2k channel and other groups, nor did the police.

‘THE EXTRA MILE’

Pereira is among the advocates who argue that social media companies should do more to screen the content available on their platforms.

In January, she was asked to assist in a report made about a Facebook account that was stealing and screenshotting images of women, as well as impersonating them.

“While numerous reports were made, nothing has been done to remove the account to date. When faced with the issue of circulation of nude images, time is of the essence and a delay in taking immediate action is dangerous,” Pereira said, noting that it exposed the victims to further harassment, humiliation, and risks of suicide.

A spokesperson for Facebook – which owns Instagram and WhatsApp – said the company had “zero tolerance for the non-consensual sharing of intimate images, or threats to share those images without permission”.

She said artificial intelligence was used to detect this sort of content before it was reported, and added that Facebook had specially trained teams that quickly removed pictures or videos once they had been reported.

“We are also able to use photo-matching technology to prevent those images from ever being re-shared on our platforms in the future,” the spokesperson said.

Facebook removed more than 28 million pieces of content showing adult nudity and sexual activity between October and December last year, while Instagram took down more than 11 million during the same period. Most of it was removed before users reported it, according to the spokesperson.

Clare McGlynn QC, professor of law at Durham University in Britain, said social media companies such as Facebook and TikTok had begun to take action against intimate image abuse.

“[But] we must keep up the pressure for them to respond to victims. We must hold them at their word and try to eliminate this material from their platforms,” she said, noting that it was important to invest further resources in developing the technology to track, trace and remove non-consensual material.

Teeruvarasu Muthusamy, a lawyer based in Malaysia, said Telegram did not have adequate reporting mechanisms to tackle the dissemination of intimate content.

“The anonymity provided by the application appears to make it the preferred social media platform for criminal activity. This is because a Telegram user can hide his phone number and still send messages, images or videos,” he said.

Telegram, which has its global development centre in Dubai but has servers all around the world, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Semenzin from the University of Amsterdam said banning pornography in general would not be an appropriate response.

“The puritanical approach of digital platforms to pornography and sexuality is creating several issues of censorship for people who use social media for sex education, or discuss sexuality through a positive approach,” she said. “What online platforms should do is take more responsibility for their role in mediating the spread of violence. [To platforms such as Telegram], online violence against women and girls is still not considered as urgent or a big issue, but just a side effect of staying online.”

The legal forces need to run an extra mile to stop this, but they are not doing it

Semenzin said normalising pornography in society and educating people about sexuality could diminish online sexual violence. “The most effective way to face such issues is promoting cultural programmes with the aim of replacing rape culture with a culture of consent,” she said.

While Rai, the student activist from Singapore, has had discussions with other women on how to best protect themselves, she insists the perpetrators should be held accountable for their actions.

“Some immediate responses include: ‘We should not post or send pictures because someone may misuse it’,” she said. “But why is it that we are concerned that someone may misuse it? Shouldn’t it be basic respect to not share someone’s images? Why are we females conditioned to be conscious of what we send and why are we not expecting and teaching perpetrators to be respectful?”

As part of her efforts, she decided to launch an online petition calling for the Singapore Police Force and State Courts to shut down Telegram channels that had been used to distribute non-consensual pictures, videos and personal information of women. By the end of May, it had garnered more than 2,000 signatures.

“The sexualisation of women doesn’t look at their skin [or] what they wear, it’s blind to everything. There are pictures of women who are just going out, who are walking in the street, and yet their pictures are still shared in these groups,” Rai said.

Amala from Malaysia, whose images were shared on Telegram, also feels that the authorities and platforms are not doing enough to help survivors such as herself.

“Deep down I know nothing will happen. It will be just another piece of paper lying around in their office collecting dust,” she said, explaining why she decided not to report her case to the police.

Amala said the authorities should join efforts to track down the administrators of Telegram groups. “I’ve learned it is hard to catch anonymous [users and administrators] because of Telegram’s privacy regulations, but nobody said it is impossible. I do feel like the legal forces need to run an extra mile to stop this, but they are not doing it.”

It was several weeks before she was able to talk about what had happened to her. Even her best friend had no idea what was going on.

Since sharing her story, however, Amala has received support from other women who understand the ordeal she has gone through. But there is still hopelessness in her tone, the disappointment of someone who has had her privacy invaded by thousands of strangers on multiple occasions.

“I hate to admit it, but my pictures were all over Telegram again and I felt nothing,” she said.

Unless those who could make a difference acted fast enough, Amala said, women would continue facing the same risks over and over again.

“I got desensitised,” she said. “It has affected me to the point where I know nothing will make those vultures stop.”

*The names of survivors and people working to combat image-based abuse have been changed to protect their identities

Credits Lead reporter and project coordinator: Raquel Carvalho Reporting team: Sonia Sarkar (India); Tashny Sukumaran (Malaysia); and Lee Min-young (The Korea Times, South Korea) Graphic artist: Kaliz Lee Copy editor: Hari Raj With support from: