What Malaysia can learn from the Lee Kuan Yew family feud in Singapore

A public apology from Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong stands in stark contrast to the silence of Malaysian leader Najib Razak regarding the 1MDB scandal

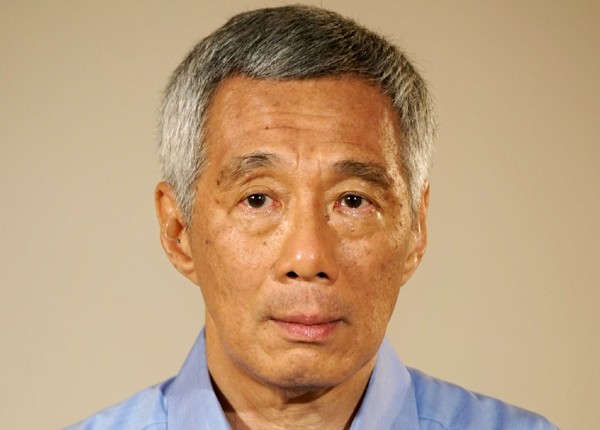

As the Lee Kuan Yew family feud transfixes Singapore, across the causeway Malaysians are marvelling at the manner in which the Lion City’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has addressed what might appear to some to be a private matter.

Lee Hsien Loong, the son of Singapore’s founding leader Lee Kuan Yew, is locked in a row with two siblings over the fate of their father’s estate at 38 Oxley Road. Lee Kuan Yew had in his will ordered the bungalow to be demolished, but the prime minister questions the making of the will and wants the government to decide whether the house ought to be preserved. His siblings want it demolished and have accused the prime minister of seeking to use the home as a monument to enhance his political capital – and to use Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy to burnish his son Li Hongyi’s political credentials.

Sons, mothers, money and memory: Theories about the Lee Kuan Yew family feud

The bitter family row broke into the public domain last week, when the siblings released a six-page memo to the media, prompting much national reflection in a land long-used to extreme discretion on behalf of its leading politicians.

What Lee Hsien Loong did next may be one of the most remarkable things in the whole long, sorry saga. On Monday, he apologised to the Singapore publicfor the pain and distress he said the row had caused them. He also said he would grant government MPs a free vote when he gives the issue a full airing in the legislature on July 3.

For Malaysians, Lee Hsien Loong’s openness, for better or worse, serves in stark contrast to how their prime minister, Najib Razak, has handled revelations that implicate him in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) investigation by the US Department of Justice.

Instead of tackling them head on, Najib has largely remained silent. His wife, characterised by the legal brief as the “spouse of Malaysian Official Number 1”, in turn has sought to contain any potential damage by threatening to sue anyone who accused her of corruption.

Member of Parliament Ong Kiang Ming, from the Democratic Action Party, told This Week in Asia: “The decision by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong to lift the whip, and to allow members of parliament [in Singapore] from all sides to openly ask him and his cabinet any questions on the Oxley Road home is in stark contrast to the situation in Malaysia, where the members of parliament are not even allowed to ask any questions related to 1MDB to any minister, much less the Malaysian Prime Minister – who is also the finance minister.”

Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong apologises for family feud

The family feud in Singapore has triggered a political firestorm in Malaysia for deep-rooted reasons.

While the Chinese opposition parties in Malaysia cannot confirm publicly their wholesale admiration of Lee Kuan Yew – they would sound politically incorrect right before a looming general election – it is a long-held sentiment that Singapore is held up as a moral tale of what-could-have-been for Malaysia. Its impressive economic development and meritocratic policies are seen as the polar opposite of race-based policies in Malaysia in the name of affirmative action for the Malays or bumiputera that have left Chinese and Indian citizens feeling disenchanted.

That such a scandal could happen to Singapore and with the Lees, no less – known for their astute ability to combine Western education and outlook with their traditional Asian values – has come as a shock to Malaysians, especially older Chinese who remember Lee Kuan Yew well.

Singapore was part of Malaysia in 1963 for nearly two years, when Lee fought to have a more meritocratic system but before long found himself caught inextricably in the race politics of Malaysia. Before long, Singapore was booted out.

Many Malaysians have a grudging admiration for how Lee Kuan Yew had gone on to transform Singapore into a regional economic powerhouse capable of punching above its weight on international issues.

Be it Lee Kuan Yew himself or his family, Malaysians – especially the Chinese – have followed their rise in public service with avid interest since the separation of the two neighbouring countries in 1965.

But apart from the Lee Kuan Yew factor, it is also the conduct of his son, Lee Hsien Loong, in the fallout of the row that has caught the attention of the chattering class in Malaysia. What he has done is being touted as a lesson for Malaysian politicians, the prime minister in particular.

While Lee Hsien Loong was quick to apologise, Najib Razak was dragging his feet with sheer insouciance, putting the chasm between Singapore and Malaysia on immediate display. And, opposition politicians and supporters have immediately latched onto the issue.

With the hope of a snap general election in the air, opposition politicians are pouncing on the misbehaviour of ruling officials.

Who’s who in the Lee family feud?

Opposition parties in Malaysia tend to point to nations such as Singapore as exemplars of how a government can be well run.

Once they reach voting age, Malaysian citizens are immediately drilled on the importance of doing something beneficial for the country. This is further reinforced by an opposition narrative that says those who exercise their rights to vote can change the country for the better.

In particular, many think a transformation of Malaysia can be achieved, inspired by the template set forth by Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew and his colleagues in the People’s Action Party (PAP).

For decades Lee Kuan Yew spoke of the importance of education. And, his family became a personification of his own outlook on how children should be raised and should pursue impeccable educational achievements.

With degrees from Harvard University and the University of Cambridge, the children of Lee Kuan Yew had for the longest time been profiled as the paragon of meritocratic values and accomplishment and imbued with Asian values.

Recently, consistent with the growth of the apps-driven economy, Singapore’s leader was celebrated by the Malaysian IT community as a “coder”, given his studies of computer science at the University of Cambridge.

For this and other reasons, Malaysians tend to believe that Singaporeans know how to do things right.

Thus in terms of getting the next digital strategy or economic policy right, as well as good governance in general, Malaysians tend to believe that Singapore has aced it. And despite the rare public airing of a family scandal, the subsequent public apology from Lee Hsien Loong was swift and to the point.

Clearly, the Singapore leader knows how to rebuild a public reputation. The message for Najib could not be clearer: take notice.