Why China and the US will continue to squander money on spying

Our fixation with espionage tricks us into believing there is excitement in a mundane world. Most spies aren’t worth the cash spent on them – and even when the intelligence is worth having, it’s usually just ignored

Few human endeavours have such a hold on the public imagination as spycraft. The sheer volume of espionage films and television dramas flowing out of Hollywood every year attests to that.

The arrest of Jerry Chun Shing Lee – a former CIA officer accused of selling information to Beijing – understandably aroused wild excitement and speculation. Lee was said to have betrayed the CIA’s methods of communication to the Chinese government. Armed with the knowledge, Beijing allegedly killed or jailed some 20 informants working for the American spy agency in China, severely crippling its operation.

Dear China, I am a white guy and not a spy

The intrigue apparently involves building a US$100 million Chinese garden at the National Arboretum in Washington. According to the Journal, this could become a security risk “because it included a 70ft-tall white tower that could potentially be used for surveillance”. The garden is about 5 miles (8km) from the Capitol and the White House.

Take a look at history. Spycraft may sound exciting and even romantic.

In real life, however, it is far more mundane. More secret agents are probably wounded by paper cuts than enemy fire.

It does not take Francis Bacon to tell us knowledge is power. Man is by nature a social animal and we love to snoop on each other. Ancient Chinese strategist Sun Tzu dedicated an entire chapter of The Art of War to espionage. Knowing your enemy is the first step to overpowering him – this is what all cultures throughout history understand.

WATCH: Beijingers urged to report foreign spies

Yet important as it is, we often fail to see that our fixation on espionage and counter-espionage is often psychological rather than rational. Our fear of uncertainty leads us to assume the worst of others. Gaining knowledge of them is a quick way to domination, while having your secrets exposed generates existential anxiety and insecurity.

Political leaders tend to spend far more resources than necessary on intelligence (and counter-intelligence). Yet even the most efficiently run spy agency would be hard pressed to justify its bills. In 2010, the US government officially announced for the first time its total tab for intelligence spending: an eye-popping US$80 billion. This included US$53.1 billion on non-military intelligence programmes and US$27 billion on military intelligence.

Given the colossal bill it paid, Washington had little to show to the public. That year, an amateur 30-year-old terrorist tried to set off a car bomb in the busy streets of Times Square in New York. What could have been a catastrophe was narrowly averted thanks to a combination of luck, the incompetence of the bomber and a vigilant street vendor who spotted smoke coming out of the vehicle and alerted the police. The CIA and the FBI, as it turned out, had no idea what Pakistan-born Faisal Shahzad was up to until the last minute.

WATCH: ‘Soviet chic’ restaurant favoured by KGB spies reopens in Moscow

This paled in comparison with the diplomatic cables leaked by WikiLeaks in the same year, which is truly one of the most serious intelligence breaches in American history.

The biggest spying stories in history arguably took place during the second world war and the cold war. Thanks to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent declassification of wartime documents, some reliable information emerged shedding light on the costs and effectiveness of wartime intelligence work. They did not paint a pretty picture.

Spies and a magic weapon: why are Australia, NZ so suspicious of China?

Many historians of wartime secret services have concluded that spying activities contributed “almost nothing” to the Allied victory in the war. Max Hastings, in his book The Secret War, noted that “perhaps one-thousandth of 1 per cent of material garnered from secret sources by all the belligerents in [the second world war] contributed to changing battlefield outcomes.”

Often the problem is at the top. As many spies have bitterly found, your intelligence can only be as good as your master’s willingness to listen. A primary example is the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin.

One of the most famous Soviet spies was Richard “Ika” Sorge. The child of a German engineer and a Russian mother, Sorge first cut his teeth in Shanghai. The charismatic Soviet spy masqueraded as an American freelance journalist. He fervently studied every aspect of Chinese life and soon became a regular Far East stringer for a prominent Nazi publication. Sorge managed to win the complete trust of his editor and was accepted as a member of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the Nazi Party). In 1935, he was sent by the Reich to Tokyo to spy on the Japanese.

In Tokyo he managed to impress the Japanese so much that he was hired by its prime minister’s office as an expert on China. In 1939, Sorge was sent to Manchuria as an intelligence officer for Japan’s Kwantung Army to spy on the Chinese. He was simultaneously working for three leading spy agencies in the world. Thanks to his intelligence, Moscow gained invaluable insight into Tokyo’s war plan and knew Japan would not attack its eastern front unless Moscow fell under Nazi force. The Red Army swiftly shifted much of its resources in the East to the Western theatre.

This should have given the Kremlin an incredible advantage and enough time to prepare for a counter-strike. Yet those in Moscow who received and processed the reports were too fearful of offending Stalin, who firmly believed Hitler’s focus was in western Europe. In the end, the Soviets suffered astounding losses in the “surprise” German blitz.

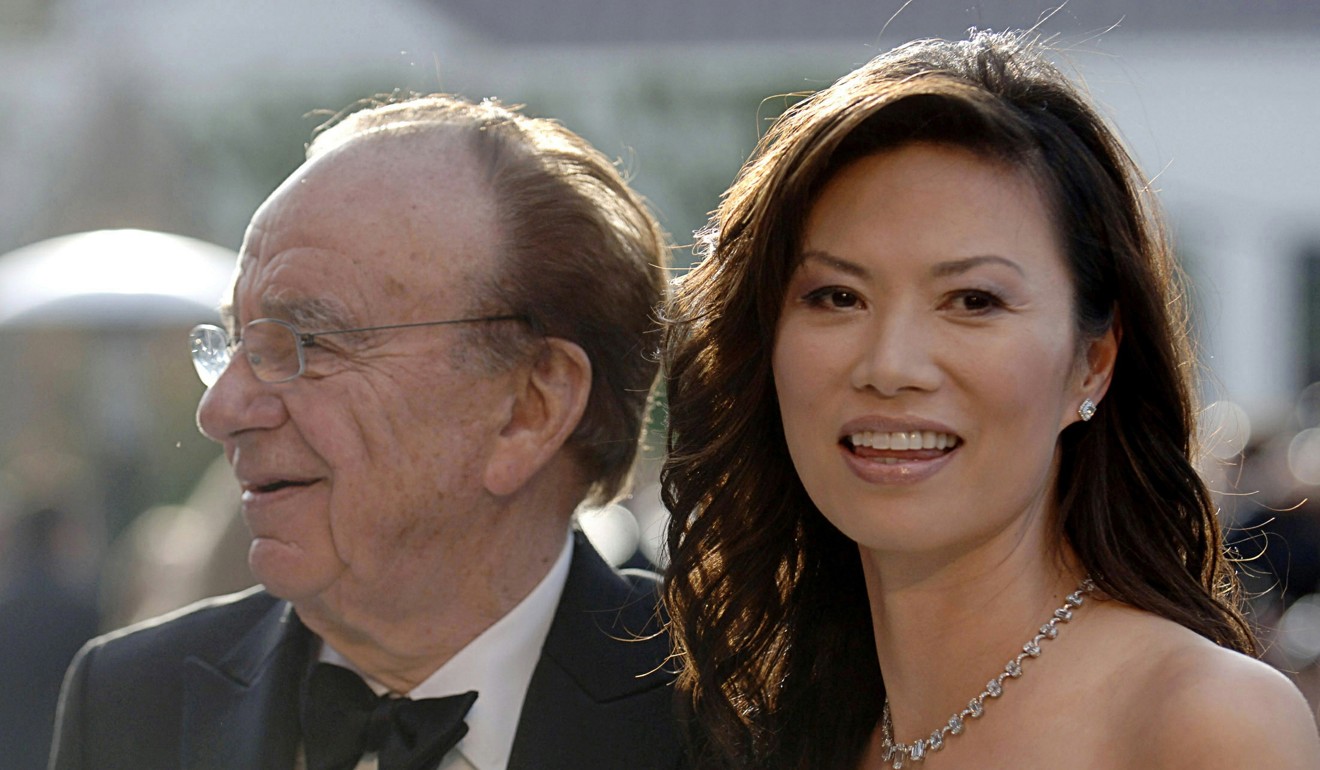

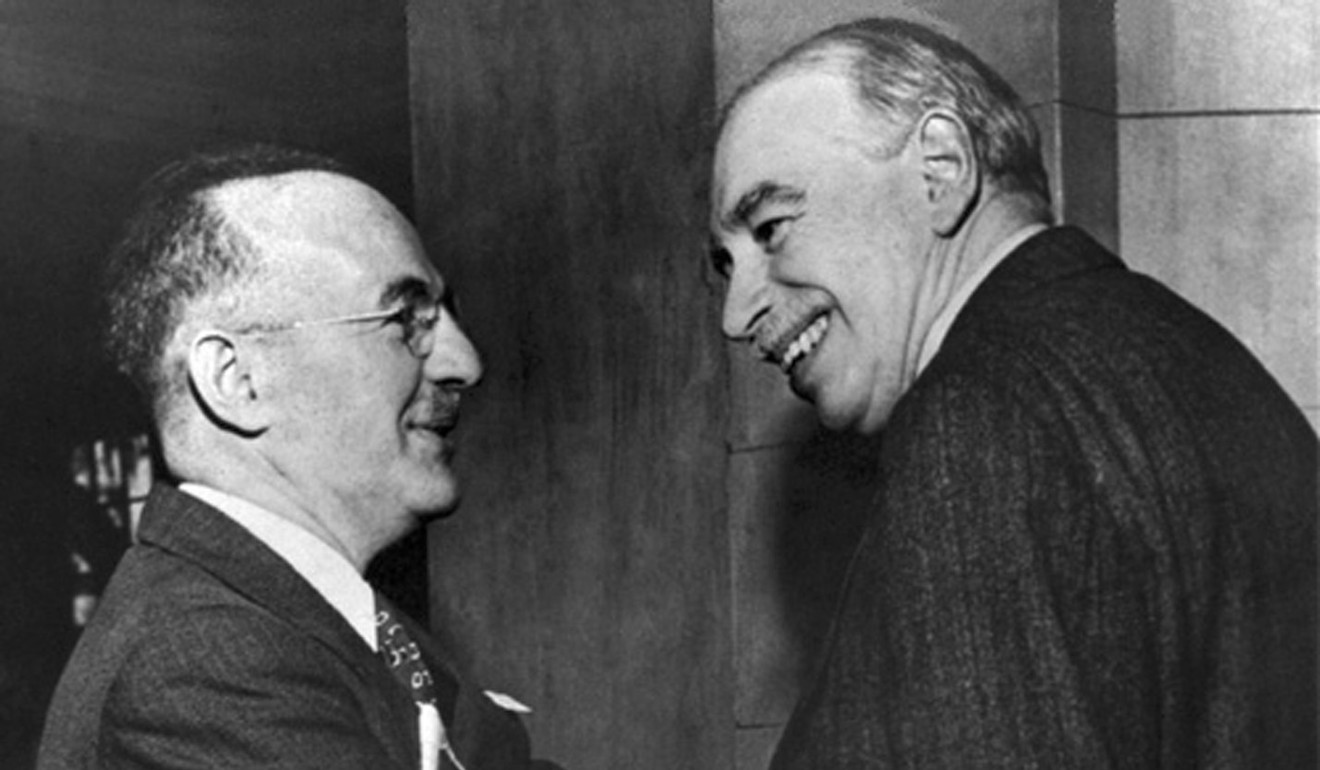

The Soviet Union remained the espionage superpower after the war. In the early days of the cold war, Moscow had far more success than London and Washington in intelligence work. Harry Dexter White, a senior US treasury official and Washington’s chief representative at the landmark Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, was later believed to be a Soviet spy. Ironically, White was also a major architect of two of the most important institutions of the capitalist world – the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

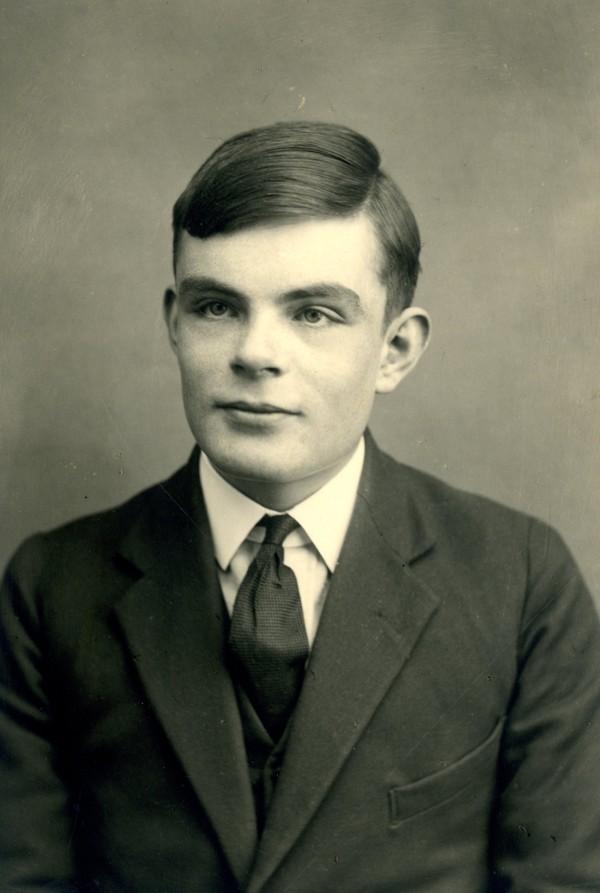

Much of the Allied forces’ intelligence success was down not to daredevil agents but brilliant young scientists in the vein of Alan Turing. Through code-breaking technology, the Allied forces managed to break into Nazi Germany’s Enigma and Imperial Japan’s Purple cipher machines. These breakthroughs had far more impact on the outcome of the war than any spy.

Until the 20th century, commanders could only discover their enemy’s movements through individual spies and direct observation. The arrival of wireless communication and radar technology changed the scene forever. Technology, not individual heroism, came to dominate intelligence work.

UNGENTLEMANLY BEHAVIOUR

Like all technological disruptions, the transformation caught many veterans off guard. In 1929, US Secretary of State Henry Stimson was furious when he found that young agent Herbert Yardley had formed a team to intercept and read other countries’ diplomatic telegraphs. Stimson ordered the cipher bureau to be shut and Yardley sacked. “Gentlemen do not read others’ mail,” he said, famously, in his memoir.

Yardley was later hired by the Chinese Nationalist government to help overhaul its intelligence work. He later wrote another exposé, The Chinese Black Chamber, which was declassified and published in 1983. He was eventually admitted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame by the US army for his contribution to the secret service.

Some 84 years later, another bright young US intelligence officer, Edward Snowden, earned the wrath of the White House. He became an outcast because he could not stand the government reading everyone’s emails. Snowden’s revelation was an eye-opener. He detailed how the NSA and the so-called Five Eyes intelligence alliance (of the US, Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand) had been running extensive surveillance programmes around the world. The age of “gentlemen do not read each other’s mail” is a distant dream.

In China, the Communist Party started off as an underground secret organisation. Intelligence and armed forces are core to its operation and form the double helix of its DNA. Run by the meticulous and capable Zhou Enlai, the communist intelligence apparatus scored stunning successes and was critical to its winning of the civil war. Its agents successfully infiltrated almost all levels of the Nationalist government.

It is said that Mao Zedong often learned details of Chiang Kai-shek’s battle plans before Chiang’s generals got the orders. Li Kenong, one of the three most celebrated Communist agents, was rewarded the rank of General in 1955 – showing the great importance the party attaches to intelligence work.

WATCH: Snowden warns of government spying in first Russia video

Because of its secrecy, the outside world often eyes the Chinese secret service with a mixture of awe and suspicion, imagining it to be an omnipresent hand controlling everything Chinese.

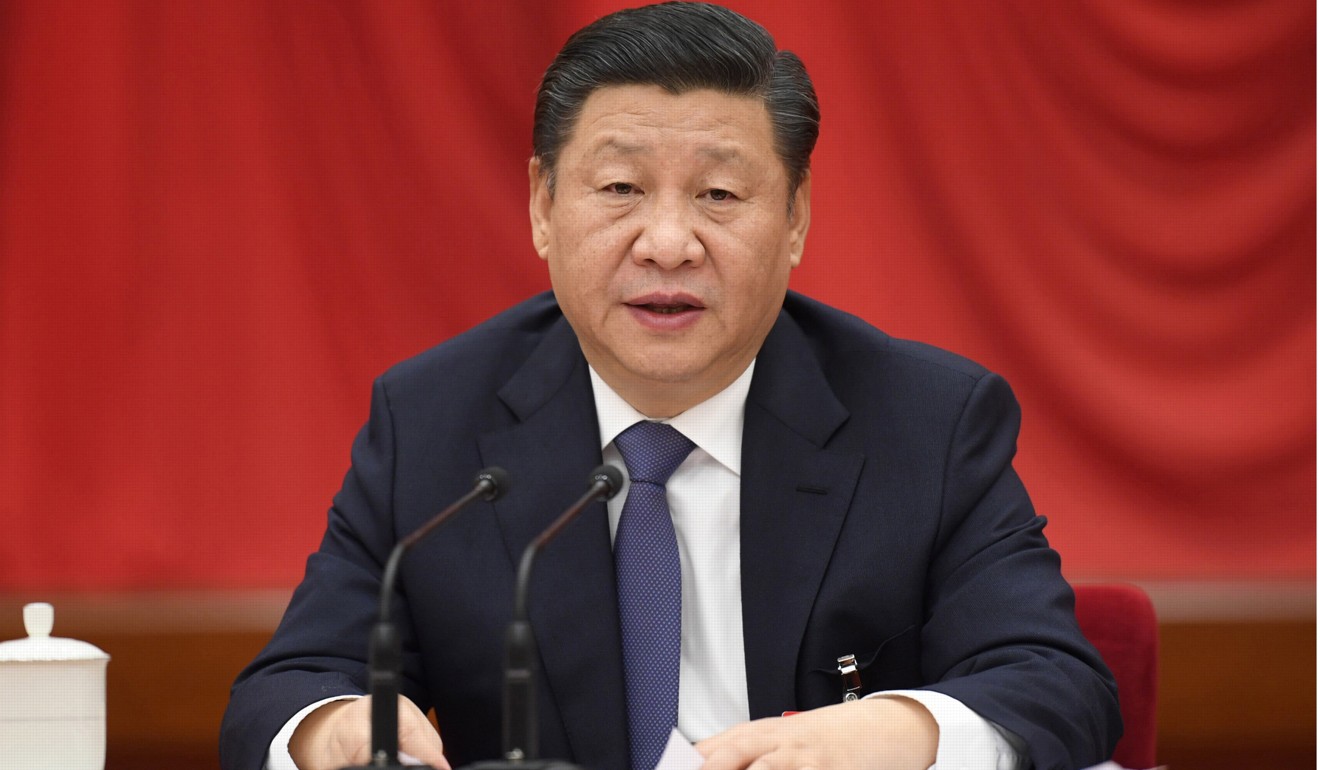

Internally, Chinese leaders hold quite an opposite view, believing the country’s intelligence work is ill-coordinated and lags behind the US.

Last year, China introduced its first national intelligence law, one of many steps Xi has taken to overhaul the country’s intelligence system and bring it up to date. In the years ahead, Beijing will aggressively restructure its secret service and security apparatus.

From Washington, Moscow and Beijing to Tokyo, governments around the world will continue to squander money on espionage and counter-espionage. It is a great shame for taxpayers – most of these operations are so secretive that they are not accountable to the public nor subject to supervision. They are inherently wasteful and do not always serve the greater good of all. If deployed elsewhere, even a fraction of the resources would solve many problems we are facing today, but it is naive to believe things will be otherwise. It is human nature to be nosy and suspicious; the craving for others’ secrets is in our blood. In God we trust, everything else we spy on. ■

Chow Chung-yan is executive editor of the South China Morning Post, overseeing daily print and digital operations