On Reflection | Louis Cha asked me if Singapore’s Straits Times would buy Hong Kong’s Ming Pao

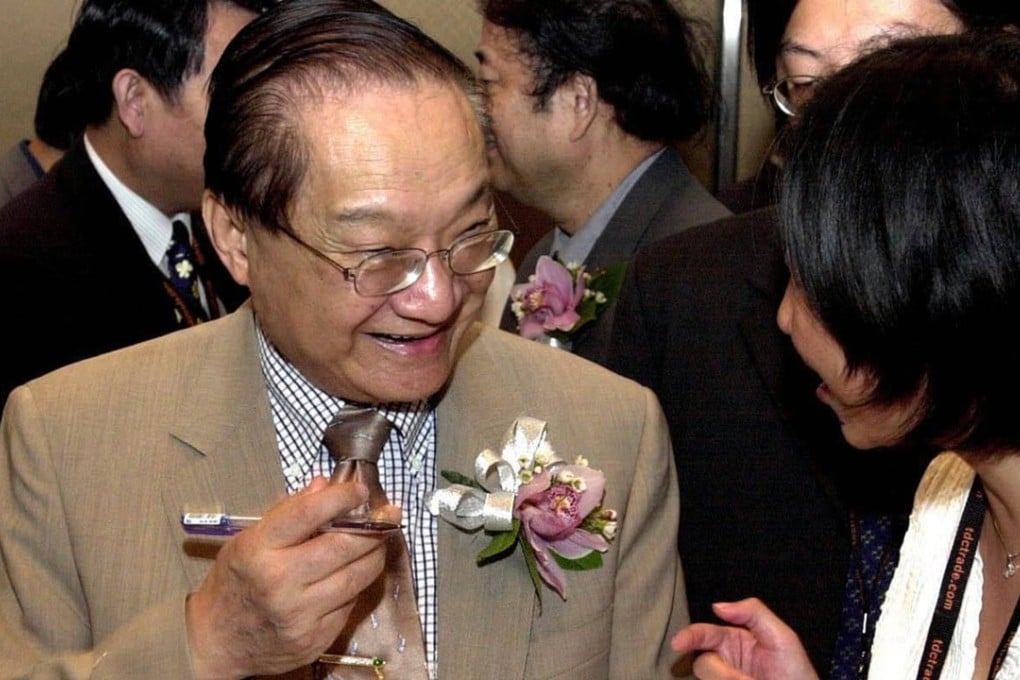

Leslie Fong remembers one of his contemporaries in journalism – the celebrated wuxia novelist known as Jin Yong, a literary great who taught him not only Chinese, but ethics, too

I know – because I was the person he sounded out through an intermediary. I had nearly forgotten about this little episode until news of his death on October 30 jolted my memory.

At that time, I was the de facto editor of Shin Min, a Chinese-language evening paper which The Straits Times acquired in 1983. I was on a three-year secondment. It was during those three years that I got to know Cha, whom I admired greatly as a novelist and journalist.

We talked, once or twice, over dinner – about China, Hong Kong, journalism and, of course, his novels. It was a great opportunity for a junior, still wet behind his ears, to learn as much as possible from a highly-respected senior in age, experience and knowledge.

Then one day, out of the blue, he asked, through an intermediary, if The Straits Times was interested in buying Ming Pao. He was planning to retire but did not want to sell his paper to just anyone with money. He thought the ST, with its financial and journalistic resources, would be in a position to take Ming Pao to a higher level.

I reported this to my bosses, and to cut a long story short, they decided, after some deliberation, not to follow up. I conveyed the answer. To this day, I have no idea how Cha felt about it. I did wonder, from time to time in the years after, how things would have turned out had a deal been struck. My guess now is that it would not have gone down very well in Hong Kong.