US-China trade war: the financial markets are focused on the wrong risk

- US bond market investors have been acting in a terrifying fashion, assuming a deflationary shock is ahead.

- Such logic ignores trends from the last 30 years of globalisation

The US political strategist James Carville once said that after his death, he would like to be reincarnated as the bond market. “You can intimidate everybody.”

Happily, however, there are some good reasons to believe the market may have got things wrong, and that the outlook may not be quite so frightening after all, or that at least it may be a different sort of scary.

At first, the prospect of deflation might not sound so terrible. Who doesn’t like lower prices?

But there are two different sorts of deflation. First, there’s the good sort, when improvements in efficiency, enabled by globalisation or new technologies such as the internet, allow goods and services to be produced more competitively.

Then there’s the bad sort. This often sets in after an economic or financial shock, when demand dries up as consumers and companies stop spending and instead hoard cash in an attempt to pay down debt and strengthen their balance sheets.

In world’s largest game of chicken, neither Trump nor Xi can blink

The trouble is that as prices begin to fall, companies have to sell ever more stuff to service their debts. But selling more stuff is tough in a demand drought, especially as potential buyers tend to postpone their purchases, expecting prices to be lower next week or next month.

As a result, the size of debt piles increases relative to output, companies go bust and workers lose their jobs, which further depresses demand in a self-reinforcing downward spiral.

This is the direction the bond market is now signposting. Investors’ inflation expectations for the next five years, as implied by the prices of US Treasury inflation-protected securities, have slumped from a rate of 1.9 per cent a year in the fourth quarter of last year to just 1.6 per cent last week.

At the same time, the yield on 10-year US Treasury bonds has fallen from 3.2 per cent to 2.1 per cent. At that rate, the return on 10-year Treasuries is 0.2 percentage point below the US three-month interest rate: a sure-fire signal in the past that a US recession is just around the corner.

But is the bond market right to be pricing in such a deflationary bust? Usually busts happen because central banks aggressively jack up interest rates to choke off a debt-driven boom, or because of an external shock, like an energy price spike.

This time around, the US Federal Reserve’s tightening has been modest, and has taken place off a very low base. As a result, borrowing costs remain comfortably below the returns US companies earn on their capital, which makes a central bank-triggered bust look unlikely.

On examination, these fears appear illogical. Tariffs themselves won’t be enough to push the US into recession. Even if the administration were to slap 25 per cent tariffs on all imports from China, the direct frictional cost would amount only to around 0.5 per cent of US GDP.

Nor is it clear that the dispute will be deflationary, as the bond market is assuming. Sure, heightened uncertainty would cause companies to delay their investment decisions, which at the margin would depress demand.

Trump’s biggest mistake: not realising China will never genuflect again

On the other hand, trade tariffs are an additional cost, which is inflationary.

But so far, the Chinese authorities have effectively blocked the yuan from weakening through the ¥7.00 to the US dollar threshold. As a result, at least some of the cost of the US tariffs is being passed on to US consumers in the form of higher sticker prices, as US retail giant Walmart has admitted. That’s clearly inflationary, not deflationary.

And if multinational companies realign their supply chains to avoid producing in China, that too will involve additional costs, and will generate additional investment demand, both of which will be inflationary.

Will Macau casinos be targeted in trade war? Odds are shortening

In short, common sense dictates that if the globalisation trend of the last 30 years was deflationary, as we know it was, it stands to reason that the reversal of that trend will now be inflationary.

Of course, in the longer term this may throw up a whole different set of challenges. But it does suggest that, in the near term, the big bad bond market is focusing on the wrong risk, and that when it wakes up to the true picture, there could be a very sharp reversal in financial markets indeed. ■

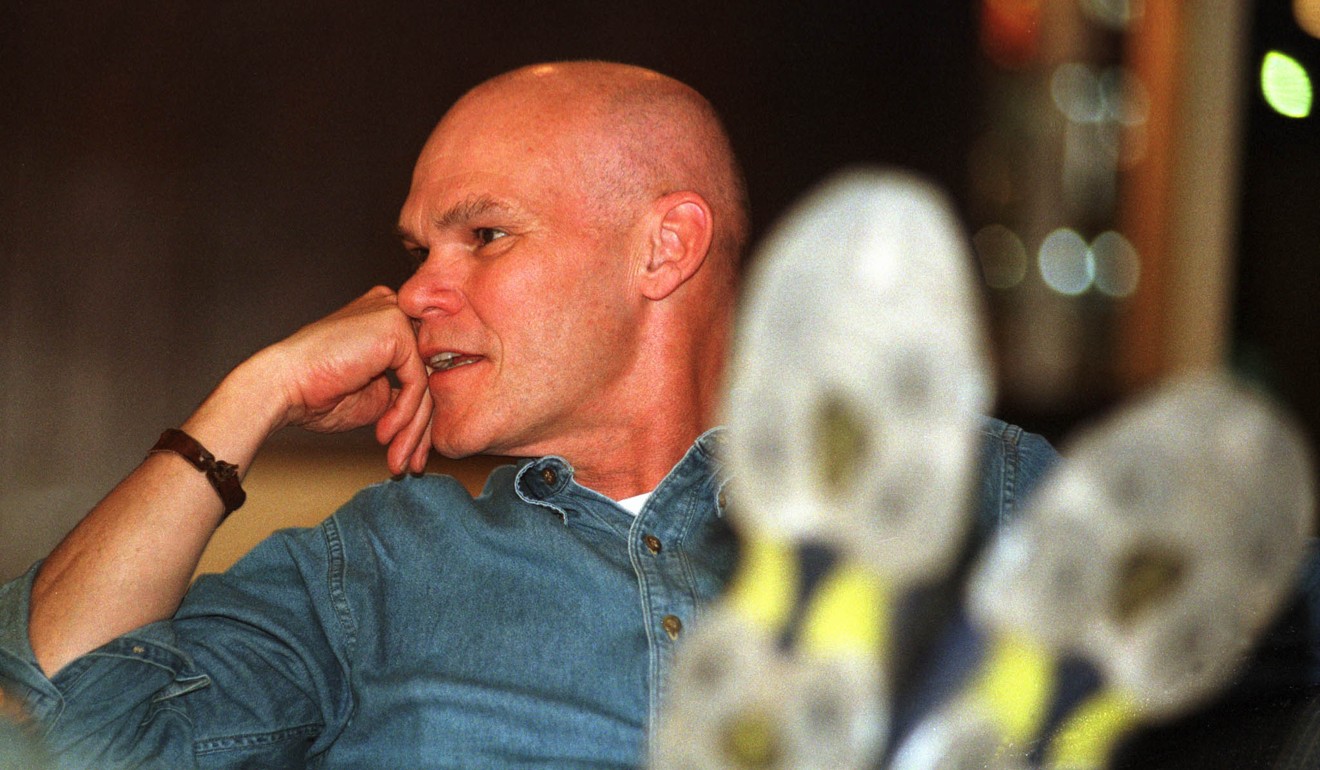

Tom Holland is a former SCMP staff member who has been writing about Asian affairs for more than 25 years