What’s to stop Hong Kong’s ‘well water’ mixing with Beijing’s ‘river water’? Nothing, the extradition law mess proves it

- When Hongkongers protested against the Tiananmen crackdown, Jiang Zemin said the “well water should not mix with the river water”

- Thirty years on, it’s apparent there’s no filter to stop that happening

In reaction to massive protests in Hong Kong against Beijing’s bloody military crackdown on the student-led pro-democracy movement of 1989, Jiang Zemin – the president at the time – quoted the Chinese idiom that “the well water does not mix with the river water”. Jiang’s point was that Hong Kong should not interfere in the affairs of mainland China and that, likewise, mainland China should not interfere in Hong Kong’s.

But since the handover of Hong Kong’s sovereignty from Britain to mainland China in 1997 – under the formula of “one country, two systems” – the two types of water have, increasingly, mixed together as economic integration between the two communities has grown.

The recent controversy in Hong Kong over a bill that would allow for extradition to the Chinese mainland is just the latest such instance of the mixing of the waters, to use Jiang’s metaphor, to have occurred over the past two decades.

Under the concept of “one country”, it is fair to expect Hong Kong and the mainland to forge a relationship with each other that is much closer than their relationships with foreign nations. They should, therefore, join hands to fulfil international obligations. Extraditions are one such instance of these. Both Hong Kong and the mainland are part of a global anti-crime effort aimed at upholding justice across borders. So given the rise of cross-border crimes – such as corruption, drug trafficking, counterfeiting and cyber offences – the need for some kind of extradition process between Hong Kong and the mainland is becoming more apparent.

From Singapore to Manila, how Asia sees Hong Kong protests

However, it should be remembered that under the concept of “two systems”, Hong Kong is also accorded its own legal and economic systems, which are supposed to offer a more robust protection of civil liberties than anywhere on the mainland under one-party communist rule.

It sounds rational for the Special Administrative Region’s government to argue that a new extradition bill is needed to plug a legal “loophole” and prevent Asia’s “world city” from becoming a haven for criminals from the mainland.

Currently, Hong Kong has signed agreements covering extradition with 20 nations and mutual legal assistance with 32 others, covering all major developed free democracies, including all G7 nations. Mainland China has signed extradition treaties with 23 nations, most of which are less developed countries. But China has also recently signed such treaties with Italy, France and Spain, though its extradition buddies do not yet include Australia, Canada, the UK and the US.

Hongkongers should welcome an extradition treaty with the mainland, as long as a “dual criminality” approach is strictly applied. That is to say, that only crimes punishable in both jurisdictions – such as murder and rape – should be classified as extraditable.

The reason that the extradition bill has provoked such unprecedented opposition from all walks of life – from legal professionals to rights activists to foreign investors (and even among pro-Beijing elements) is that it has insufficient safeguards guaranteeing fair trials and the protection of rights.

Under Hong Kong’s current extradition treaties with other countries, the government can only finally approve an extradition after it has gone through due legal procedures, including court hearings and appeals. Under the new bill, local courts would consider only whether there was sufficient prima facie evidence to convict the suspect. The new bill also effectively diminishes the role of the Legislative Council in giving oversight of extradition arrangements with the ad hoc arrangements it is trying to cover.

Some powerful business groups have argued the bill, if passed, would damage Hong Kong’s competitiveness, while foreign investors in the city fear Beijing could use it to retaliate against foreign nationals, who work in or travel to Hong Kong.

Hong Kong extradition law protests: is this a colour revolution?

Many among the more than 1 million people who took to the streets on June 9 to oppose the bill – and the nearly 2 million who did the same on June 16 – will no doubt be worried that passing the extradition bill could pave the way for the government to revive the stalled national security law that was shelved in 2003. That bill, which prompted half a million people to march, could lead to maximum life prison terms for treason, theft of state secrets, sedition, secession and subversion.

In a city often regarded as a territory of workaholics more concerned with economics than politics, the recent demonstrations suggest not only fear and anger, but distrust of the mainland’s judicial system. Distrust, too, of the lack of rule of law on the mainland, where arbitrary detentions and poor prison conditions are commonly alleged.

Many are also worried about the lack of legal protection for human rights on the mainland. Beijing has not yet ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, despite signing up to it in 1998. The covenant applies to Hong Kong under the city’s Basic Law.

There have been reports that political dissidents, activists, human rights lawyers, independent journalists, and even liberal academics have been subject to arbitrary detention, unfair trial and torture on the mainland, though Beijing denies all accusations of human rights abuses.

It’s not just Hong Kong, Asia has a rich history of protests: here are 5

That is why Hong Kong’s current law regarding fugitives – passed before Hong Kong’s sovereignty passed from Britain to China – explicitly states it does not apply to requests for extradition and legal assistance from the mainland government.

The fear being stoked is that the latest bill in its present form could enable Beijing to ask the Hong Kong government to extradite political dissidents, civil rights activists and critics of the Chinese government, for trial in mainland courts. This misunderstanding, borne out of a lack of trust or wilful instigation, has been purveyed even though political crimes are excluded from the 37 listed in the bill.

The saga speaks volumes about how difficult it is to accomplish two contradictory goals: achieving sovereign unity while maintaining a constitutional distance between two different political entities. The crux of the matter is the lack of a filter to prevent the well water and the river water from getting mixed up. ■■

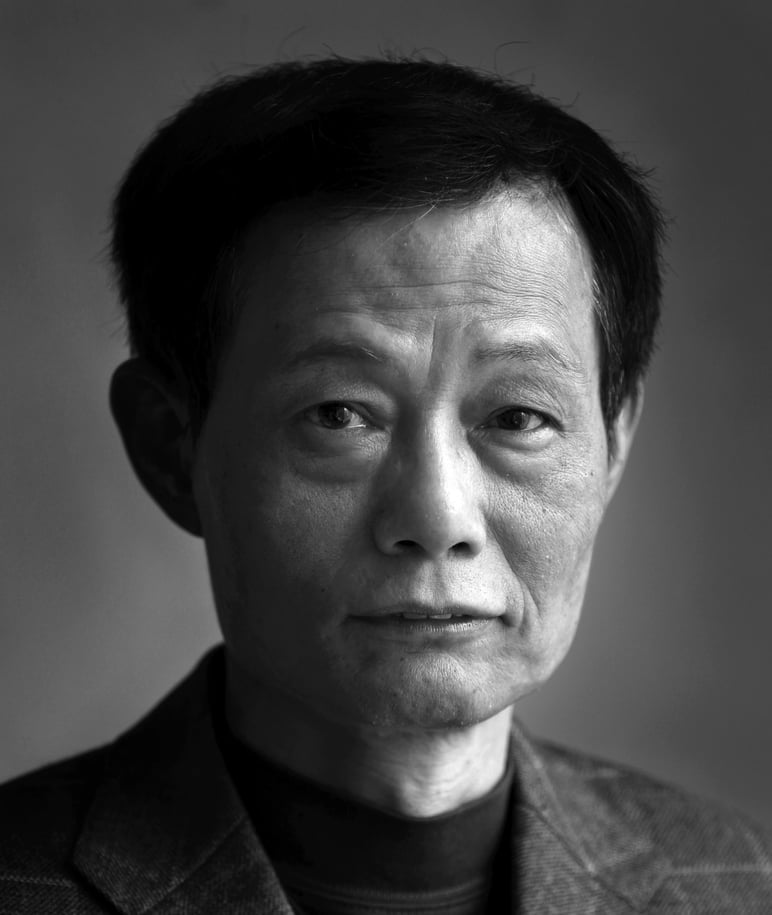

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on the topic since the early 1990s