China Briefing | No rocket science: for China to beat US in tech, it must boost R&D investment and cultivate world-class talent

- China’s race for tech supremacy has become more urgent amid worsening ties between Beijing and Washington

- As senior Party officials prepare to set new five-year economic goals, challenges include expanding China’s research sector and nurturing more top scientists

From Monday, senior Chinese officials are set to converge on Beijing for a key meeting to thrash out detailed five-year targets for economic growth, and long-term development goals for 2035.

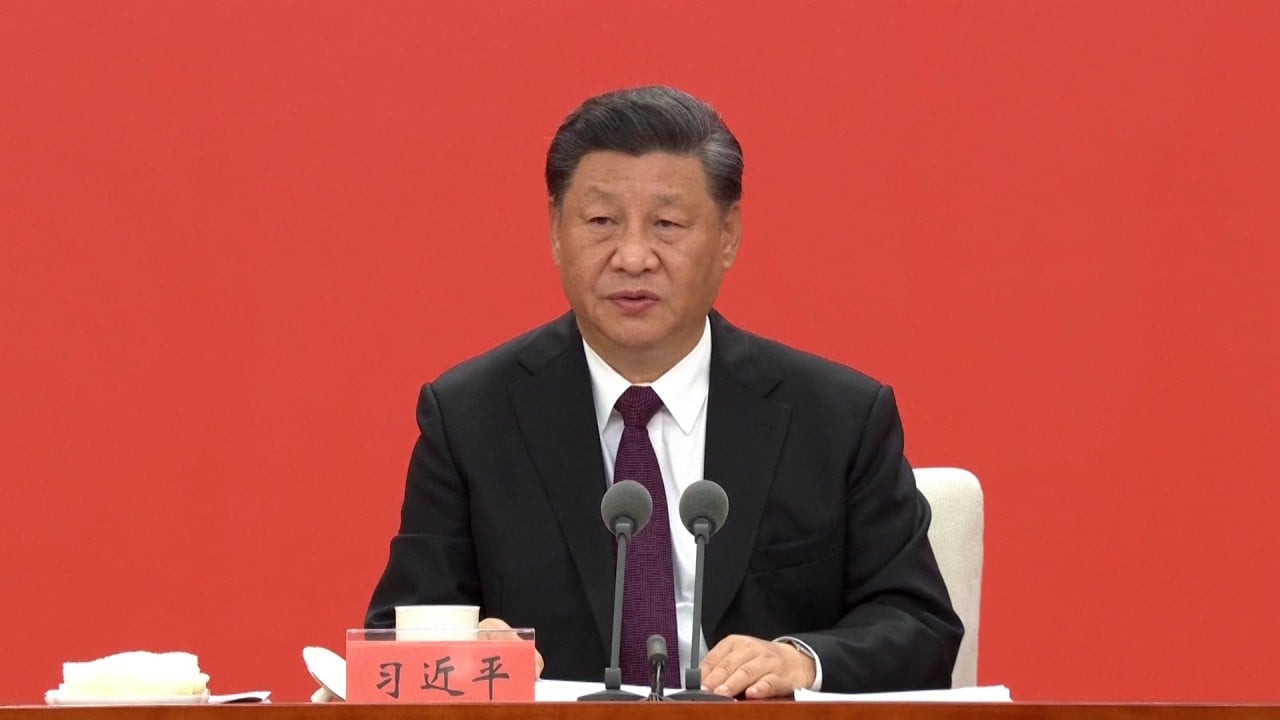

While visiting a hi-tech company in Guangdong as part of the trip, Xi said China needed to “take the road of self-reliance on a higher level” as the country is faced with “major changes unseen in a century”.

02:01

Xi Jinping vows to promote Shenzhen as global trade hub during 40th anniversary visit

One week ago, Xi chaired a special study session for the Communist Party’s 25-member Politburo on the importance and urgency of China winning the race on quantum science and technology, which he said would lead a new round of technological revolution and industrial transformation.