Why the Quad doesn’t spell the future of Asia’s relationship with China

- Different geopolitical interests and vulnerabilities mean the security alliance between Australia, India, Japan and the US will not alter the course of the region’s history

- But the big geopolitical game in Asia is not military but economic – and a massive economic ecosystem centred on China is evolving in the region

This article was first published in Foreign Policy.

This is why it was unwise for Australia to slap China in the face publicly by calling for an international inquiry into China and the origins of Covid-19. It would have been wiser and more prudent to make such a call privately. Now Australia has dug itself into a hole. All of Asia is watching intently to see who will blink in the current Australia-China stand-off. In many ways, the outcome is predetermined. If Beijing blinks, other countries may follow Australia in humiliating China. Hence, effectively, Australia has blocked itself into a corner.

And China can afford to wait. As the Australian scholar Hugh White said: “The problem for Canberra is that China holds most of the cards. Power in international relations lies with the country that can impose high costs on another country at a low cost to itself. This is what China can do to Australia, but [Australian Prime Minister] Scott Morrison and his colleagues do not seem to understand that.”

07:55

Australia ditched diplomacy for ‘adversarial approach’ to China and ‘a pat on the head’ from US

Significantly, in November 2019, former prime minister Paul Keating warned his fellow Australians that the Quad would not work. “More broadly, the so-called ‘Quadrilateral’ is not taking off,” he told the Australian Strategic Forum. “India remains ambivalent about the US agenda on China and will hedge in any activism against China. A rapprochement between Japan and China is also in evidence … so Japan is not signing up to any programme of containment of China.” While India has clearly hardened its position on China since Keating spoke in 2019, it is unlikely to become a clear US ally.

Yet this is not a new phenomenon. With the exception of the first half of the 20th century, Japan has almost always lived in peace with its more powerful neighbour. As the East Asia scholar Ezra Vogel wrote in 2019: “No countries can compare with China and Japan in terms of the length of their historical contact: 1,500 years.” As he observed in his book China and Japan, the two countries maintained deep cultural ties throughout much of their past, but China, with its great civilisation and resources, had the upper hand.

If, for most of those 1,500 years, Japan could live in peace with China, it can revert to that pattern again for the next 1,000 years. However, as in the famously slow kabuki plays in Japan, the changes in the relationship will be very slight and incremental, with both sides moving gradually and subtly into a new modus vivendi. They will not become friends any time soon, but Japan will signal subtly that it understands China’s core interests. Yes, there will be bumps along the way, but China and Japan will adjust slowly and steadily.

India and China have the opposite problem. As two old civilisations, they have also lived side by side over millennia. However, they had few direct contacts, effectively kept apart by the Himalayas. Unfortunately, modern technology has made the Himalayas no longer insurmountable, hence the increasing number of face-to-face encounters between Chinese and Indian soldiers. Such encounters always lead to accidents, one of which happened in June last year. Since then, a tsunami of anti-China sentiment has swept across India. Over the next few years, relations will go downhill. The avalanche has been triggered.

Yet China will be patient because time is working in its favour. In 1980, the economies of China and India were the same size. By 2020, China’s had grown five times larger. The longer-term relationship between two powers always depends, in the long run, on the relative size of the two economies. The Soviet Union lost the Cold War because the US could vastly outspend it. Similarly, just as the US presented China with a major geopolitical gift by withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement in 2017, India did China a major geopolitical favour by not joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

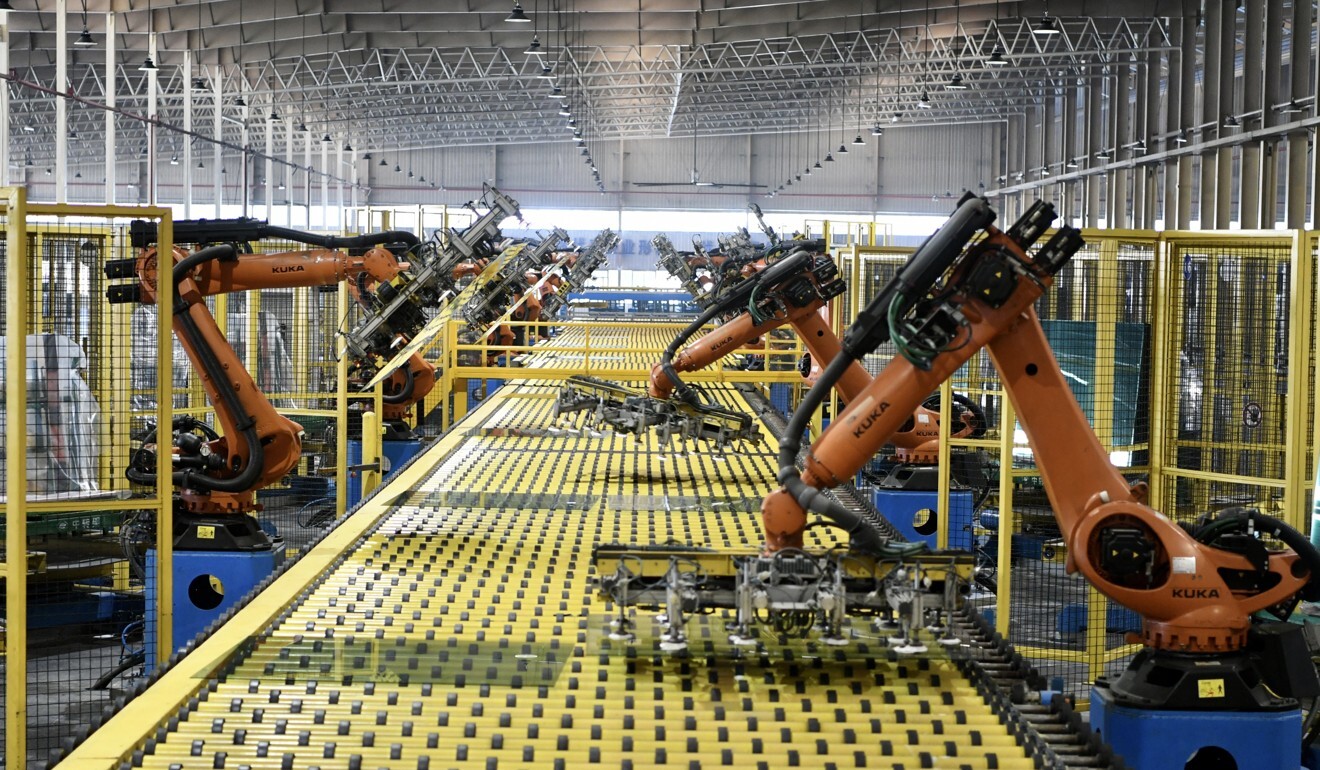

Economics is where the big game is played. With the US staying out of the TPP and India out of the RCEP, a massive economic ecosystem centred on China is evolving in the region. Here’s one statistic to ponder: in 2009, the size of the retail goods market in China was US$1.8 trillion compared with US$4 trillion in the US. Ten years later, the respective numbers were US$6 trillion and US$5.5 trillion. China’s total imports in the coming decade will likely exceed US$22 trillion. Just as the massive US consumer market in the 1970s and 1980s defeated the Soviet Union, the massive and growing Chinese consumer market will be the ultimate decider of the big geopolitical game.

This is why the Quad’s naval exercises in the Indian Ocean will not move the needle of Asian history. Over time, the different economic interests and historical vulnerabilities of the four countries will make the rationale for the Quad less and less tenable. Here’s one leading indicator: no other Asian country – not even the staunchest US ally, South Korea – is rushing to join the Quad. The future of Asia will be written in four letters – but they are RCEP, not the Quad.

Kishore Mahbubani, a distinguished fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute, is the author of Has China Won? The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy.