Philippines’ Duterte: from war on drugs to war on media?

A row with Rappler raises fears the strongman leader has his sights on setting the news agenda

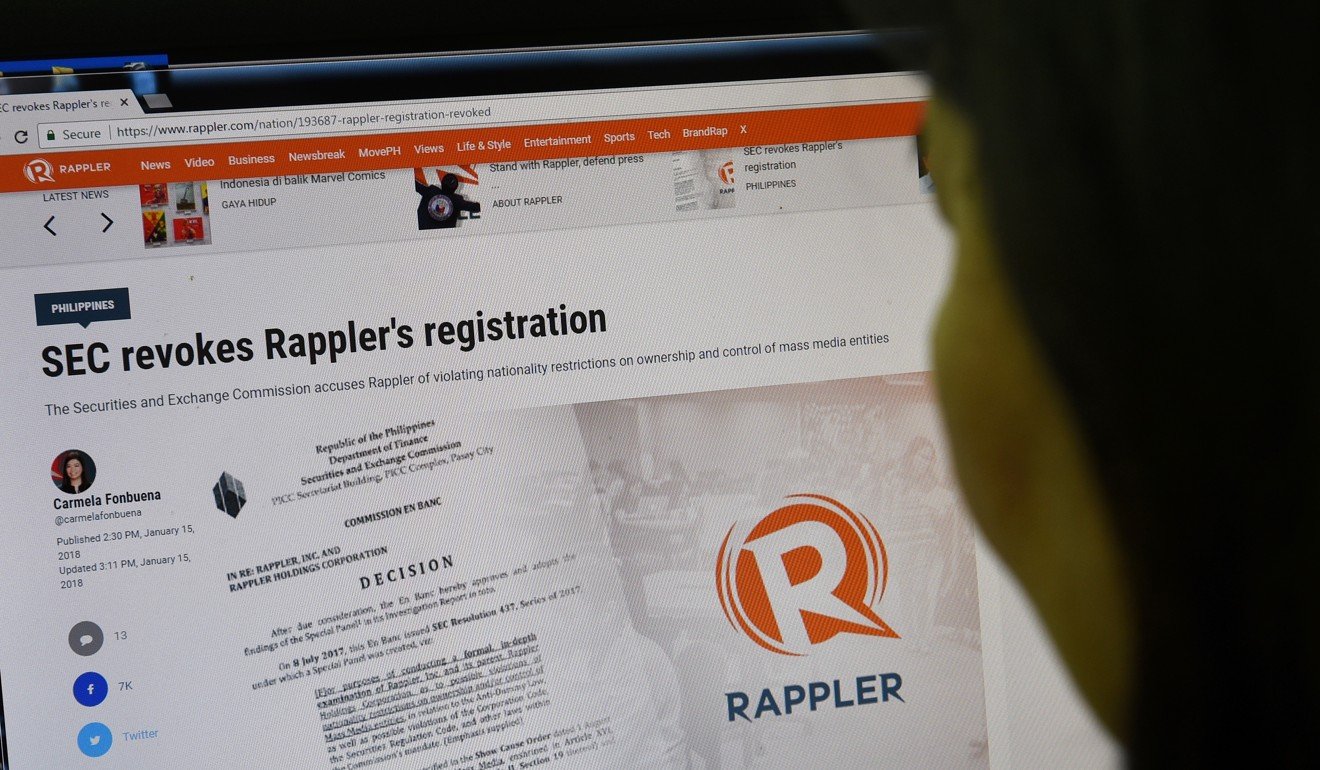

It wasn’t hard to grasp why the Filipino president was so angry. Just a day earlier, on January 15, Rappler’s licence had been revoked in a move the Committee to Protect Journalists labelled a “grave affront to Philippine press freedom”.

Duterte might well have expected that would be the end of Rappler’s sniping, yet here it was, back again and in full voice, with a hard-hitting investigation targeting Duterte’s right-hand man, Christopher ‘Bong’ Go, who it accused of improperly lobbying on behalf of a South Korean firm chasing a 15.5-billion-peso (HK$2.4 billion) warship procurement project.

The timing of the article must have seemed particularly galling for a strongman leader who has done little to disguise his contempt for a site long critical of his administration.

Indeed, most analysts suggest the reason Rappler is in trouble is precisely because of its uncompromising stance on Duterte’s drug war, which has resulted in the extrajudicial killing of thousands since he took office in 2016 and prompted widespread international condemnation, including from the UN.

Unbroken: the Philippine senator opposing Duterte’s drug war

Yet the official story by the Securities and Exchange Commission, which effectively revoked Rappler’s licence but did not require it to shut immediately, is that the site had violated constitutional requirements for media companies to be fully owned by Filipinos. (Rappler, for its part, admits having two foreign investors – Omidyar and North Base Media – but insists the investments satisfied conditions that allow companies to access international funding without ceding ownership. It also argues that other media companies in the Philippines have used similar schemes without censure).

RAPPLER RIPPLE EFFECT

Whatever the commission’s real motive, Rappler is unbowed and appears likely to continue with its combative stance. CEO Maria Ressa has attacked the commission’s decision as being handed down “without due process” and has vowed to “continue to push the government to respect and maintain the rule of law”.

However, analysts warn the controversy is already snowballing into a battle over media censorship that goes far beyond this single outlet.

Since the commission’s move against Rappler, pro-Duterte politicians in the national legislature have resurrected proposals to change the country’s 1987 constitution to give the government greater control over the kind of information the media can report.

In Duterte’s Philippines, resistance is futile

Under Article III, Section 4, the constitution presently says that, “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press, or the right of the people to peaceably assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances.”

Spurred on by the controversy surrounding Rappler, House Deputy Speaker Fredenil Castro has proposed qualifying this to cover only the “responsible exercise” of freedom of expression. Analysts warn such a move would be open to abuse by a government seeking to silence opposition.

As Danilo Arao, a journalism professor at the University of the Philippines, notes: “The deceptive use of the adjective ‘responsible’ means that ‘irresponsible’ journalism and activism could be subjected to government regulation.”

The proposal is clearly an attack on the people’s basic freedoms

SOUND FAMILIAR?

This isn’t the first time the government has attempted such a move. In 2006, a group formed by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo also took aim at Section 4 with a plan to replace the term “freedom of speech” with “the responsible exercise of the freedom of speech”. That move was shelved following a public outcry and condemnation from journalists and media groups hope there will be similar opposition this time around.

“This is unacceptable and contravenes the self-regulation in media that should be strengthened, along with the people’s right to protest. The proposal is clearly an attack on the people’s basic freedoms,” Arao said.

The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines said the proposed amendment was “plain stupid” and would essentially spell the end of freedom of expression.

WATCH: A close-up view of Duterte’s war on drugs

Rappler and other publications are now calling for the media to take a united stand. Arao said this had helped shoot down the proposal in 2006, when it was opposed on two main grounds. “The main arguments then were that, one, any assault on basic freedoms is unacceptable; and two, that we cannot trust government to define ‘responsible exercise’ when it is the government that practises irresponsibility in the first place,” Arao said.

Even if media organisations can face down the proposed amendment, some commentators say the experiences of Rappler and the Philippine Daily Inquirer – another publication often critical of Duterte – show freedom of the press has already been compromised.

Prior to the Rappler controversy, Duterte had attacked the Inquirer by claiming its majority owners, the Prietos, had failed to pay taxes on a government property leased to them. The Office of the Solicitor General promptly demanded the Prietos leave the property. Duterte has also threatened to block the franchise renewal of another news firm, ABS-CBN, ostensibly for failing to air his political advertisements in the 2016 presidential elections despite taking payment for them.

While Duterte’s supporters portray recent events as the work of government departments, rather than direct moves by the president (Duterte denied having a “hand” in the commission’s ruling against Rappler, claiming he did not “give a s*** if you continue or not with your network”), critics play down the distinction. “Shortly after [Duterte’s] critical statements about [Rappler and the Inquirer], government agencies moved against both of them,” said Shiela Coronel, director of Columbia University’s Toni Stabile Centre for Investigative Journalism.

Why left-behind Filipinos back Rodrigo Duterte

“One need not look for the hand of the president,” added Rappler’s managing editor, Glenda Gloria. “One need only go back to his statements which, in a strong presidential form of government such as ours, are taken as marching orders.”

This, she said, constituted “harassment, pure and simple” and showed “intolerance of independent media, which is a crucial requisite for democracy”.

That might paint a bleak picture for press freedom, but quite how successful any such “harassment” might be in setting the news agenda is far from clear. What does seem clear, at least for now, is that the stage is set for further showdowns – with Rappler a case in point. Having so far weathered the president’s attacks and colourful remarks, the site has already decided on its next move: publishing the second part of its exposé. ■