‘Three Lees is too much’: Goh Chok Tong on leading Singapore after Lee Kuan Yew

- Singapore’s second prime minister was tasked with leading the Lion City between the reigns of Lee the father and Lee the son

- He had a vital, but underappreciated, mission: showing there was life after the death of a legend

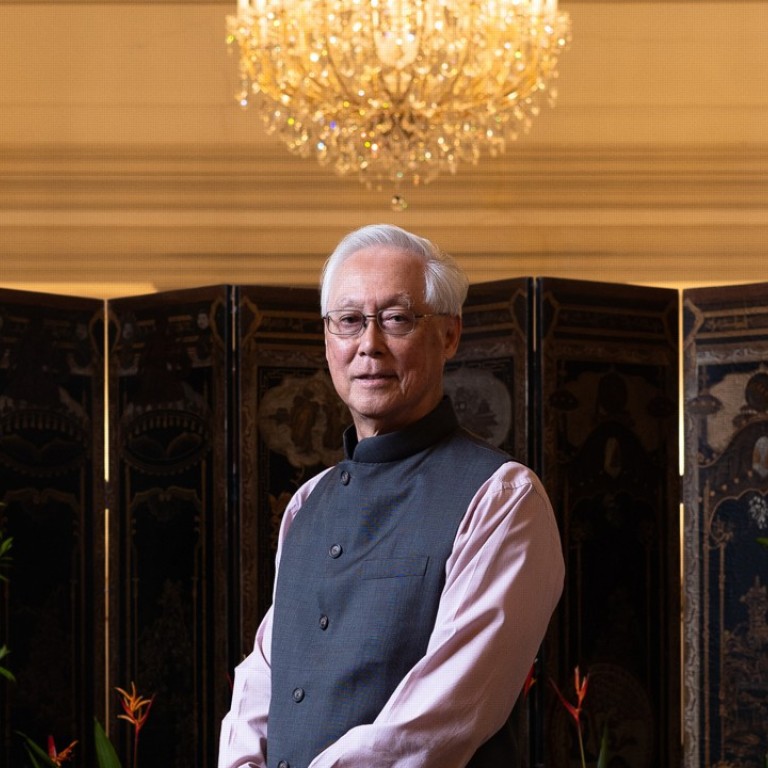

“You want to know the story of this?” Goh Chok Tong says as he plucks at the grey fabric on his chest.

It is not often that a former prime minister volunteers to share his fashion choices, so you say yes, perhaps a little too enthusiastically. He had worn a similar top in black at a public event the previous evening, getting people talking.

“So now maybe I start an India fashion fever,” he says, beaming.

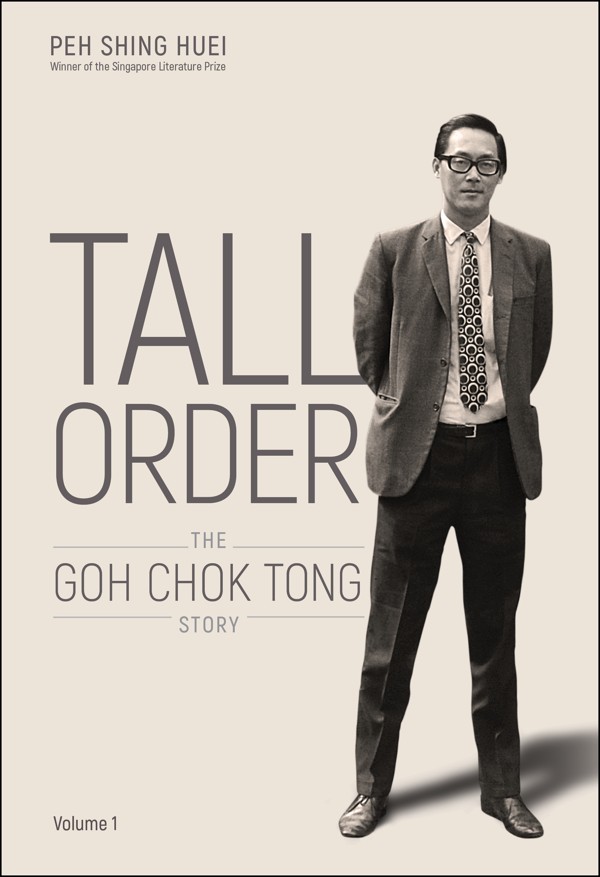

That is the thread that runs through a new book about him. Tall Order: The Goh Chok Tong Story is a portrait of a second-generation leader trying to find his own voice and steer his country in his own style, always in the shadow of a political giant.

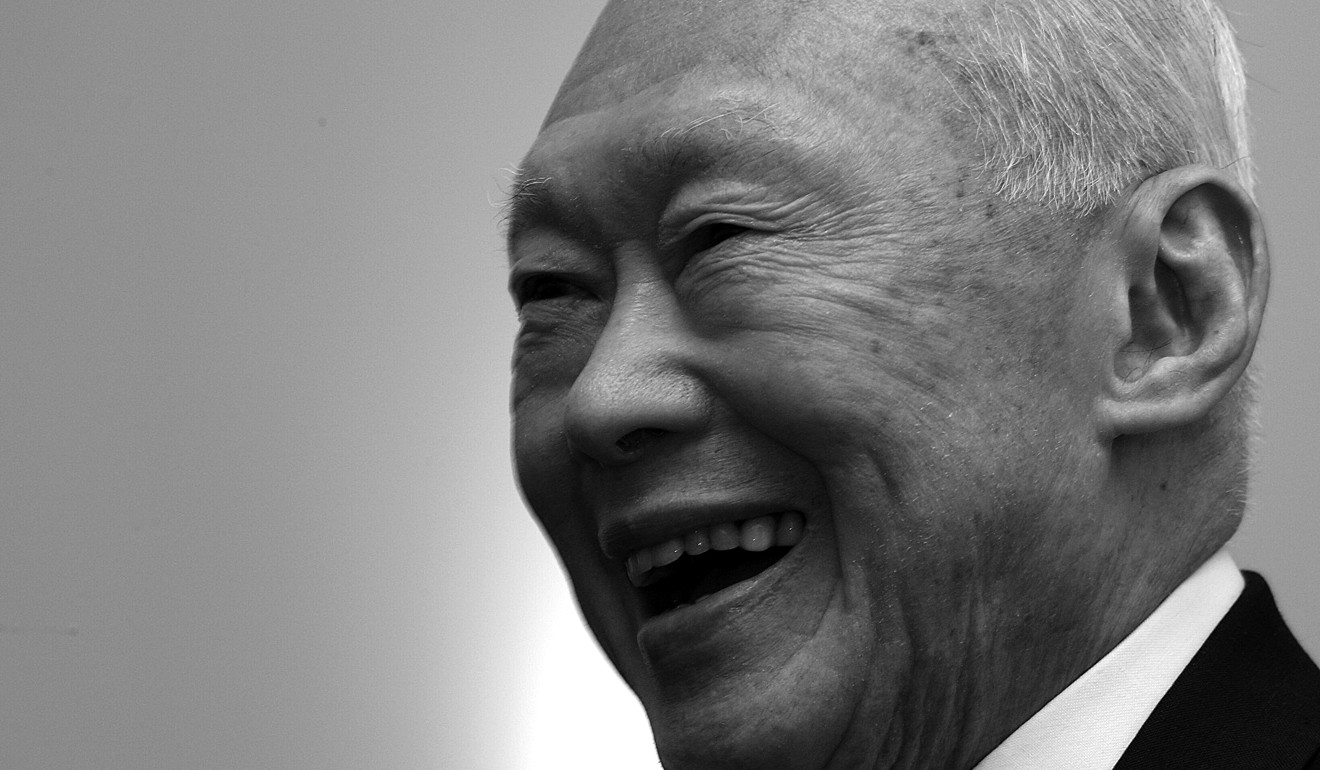

For more than three decades, Lee had powered Singapore to first world nation status, sometimes through the force of his personality, it seemed. He was so dominant on the political stage that when he started talking about succession planning in the early 1980s, few believed it.

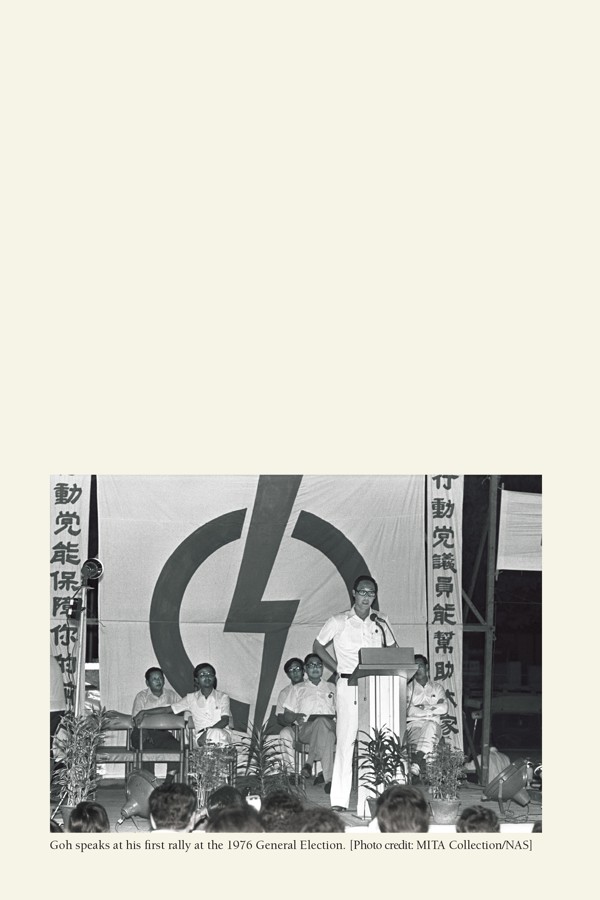

Waiting in the wings was a tall man with thick glasses, square jaw, and straight-set lips, with just the faintest hint of a curl – whether it spelt disdain or discomfort was hard to tell.

MAKING HIS OWN MARK

Goh Chok Tong served as Singapore’s second prime minister for a full 14 years, from 1990 to 2004. But on the world stage, and even in domestic politics, it was near impossible to break free from the orbit of his stellar predecessor, who remained in cabinet with the suitably ambiguous title of Senior Minister.

Compounding the awkwardness of Goh’s position, it was taken for granted that the premiership already had a younger man’s name on it. Lee Hsien Loong, the patriarch’s son and Goh’s deputy, had a date with destiny (he is the current prime minister); it was widely assumed that Goh would be little more than a seat-warmer. He was the Holy Goh, one of the gentler quips went, between Father and Son.

But one of the qualities that enabled Goh’s tenure to last far longer than most expected was probably his ability to be understated and to restrain his ego from getting the better of him. He never pretended he could fill his predecessor’s “big pair of shoes, maybe size 20, size 30”, as he once described them. When the irrepressible Lee Kuan Yew made awkwardly forthright statements – including about Goh – Goh would laugh it off, or give that enigmatic curl of the lip.

Now, three years after Lee’s death, Goh is not letting Singapore’s founding prime minister have the last word about Singapore, or about him. The first volume of his recollections of his political career, however, can hardly be described as a tell-all, and will not overturn prevailing accounts of Singapore politics.

But for Singaporeans and other close watchers of the country’s relatively uneventful political scene, the book contains enough revelations to ensure that it will fly off the shelves. For others, the book, by journalist Peh Shing Huei, sheds light on one of the most remarkable features of Singapore governance – the blend of continuity and change that has allowed a business-as-usual transition from a charismatic nationalist leader to a second-generation governing elite.

Singapore’s next prime minister: what’s taking so Loong?

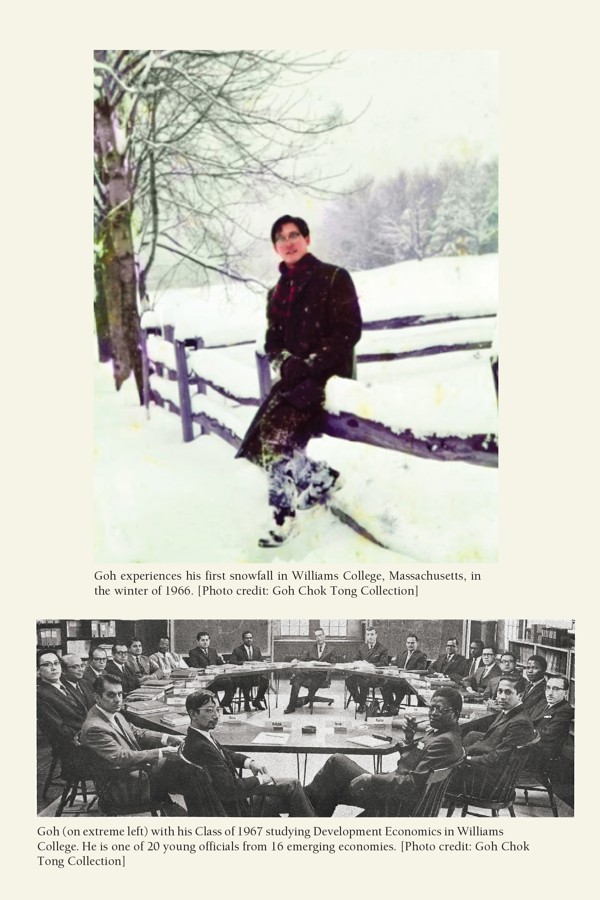

The other side of the coin, though, is less discussed. What about the successor generation? For planned successions to work, second-generation leaders have to be anointed by their predecessors, and yet not become slaves to legacy. Goh’s book provides a window into one such politician’s mind.

Now 77, Goh is still a member of parliament for the Marine Parade constituency in Singapore’s legislature. He holds the honorary position of Emeritus Senior Minister and still keeps his old prime minister’s office space in the Istana, the stately but modestly proportioned colonial-era palace off the city’s main shopping belt of Orchard Road.

This Week in Asia met him there. Goh, after a Peranakan lunch with younger colleagues and grassroots leaders, was his cheerful, relaxed self.

It seemed fitting to start with Lee Kuan Yew, as his name appears in close to 80 pages of the 272-page book. And it was this building that Lee would continue to visit until just weeks before he died at the age of 91 in March 2015.

We quip that Goh has produced typewritten answers to our questions in a fairly large font, reminiscent of Lee’s own preference for huge type and big computer screens.

“My computer screen is bigger now. By the time I am 80, my screen will be bigger, like MM’s,” he says, referring to Lee by the acronym of his last cabinet position, Minister Mentor.

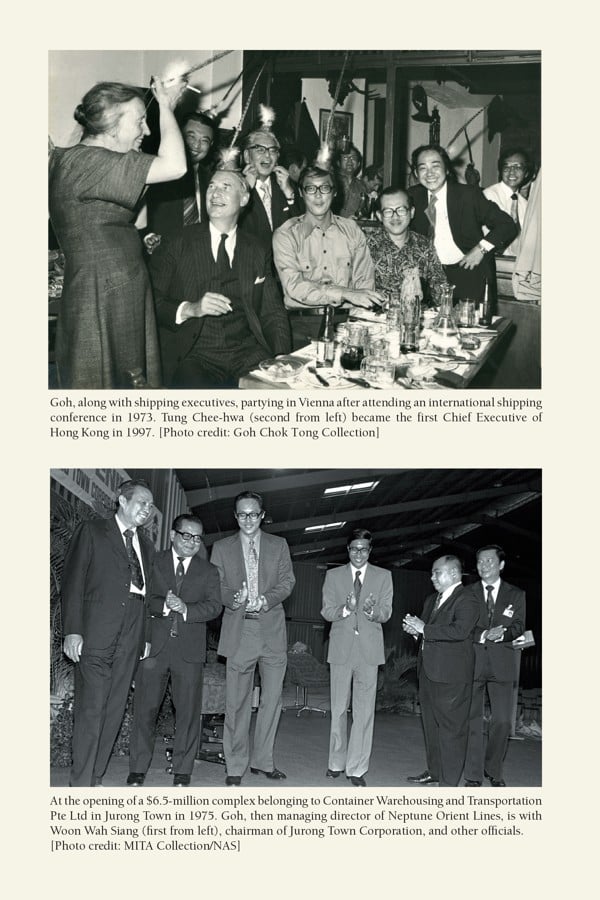

Goh talks candidly about his relationship with Lee. He likens it to one between a mentor and student, or kung fu master and disciple. Goh joined government after graduating with a degree in economics and at the age of 32, he was asked to run a floundering national shipping company, Neptune Orient Lines. In three years, the systems man in Goh had instituted new management structures and made a success of it. In the book is a picture of him partying in Vienna in 1973 after a freight conference. The revellers included shipping scion and Hong Kong’s future first chief executive, Tung Chee Hwa.

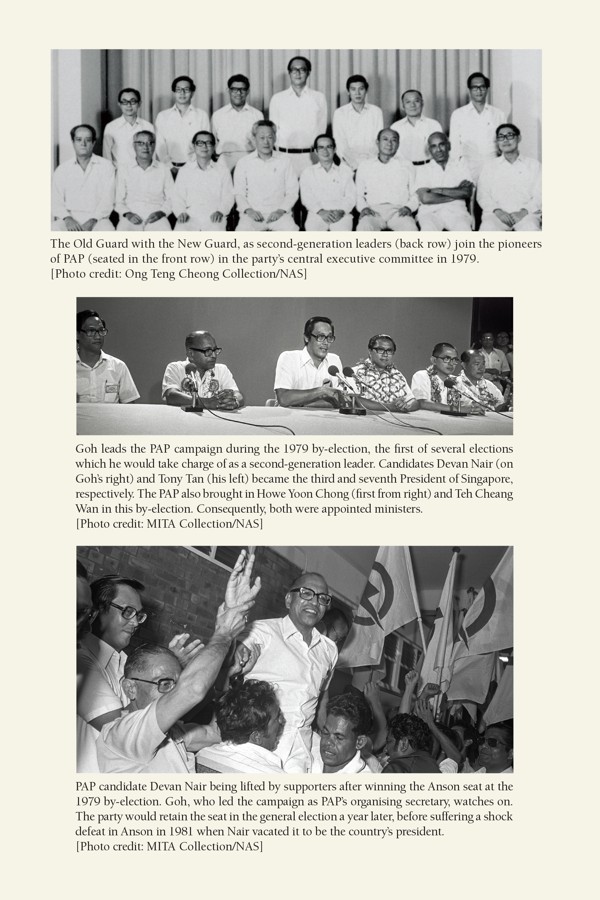

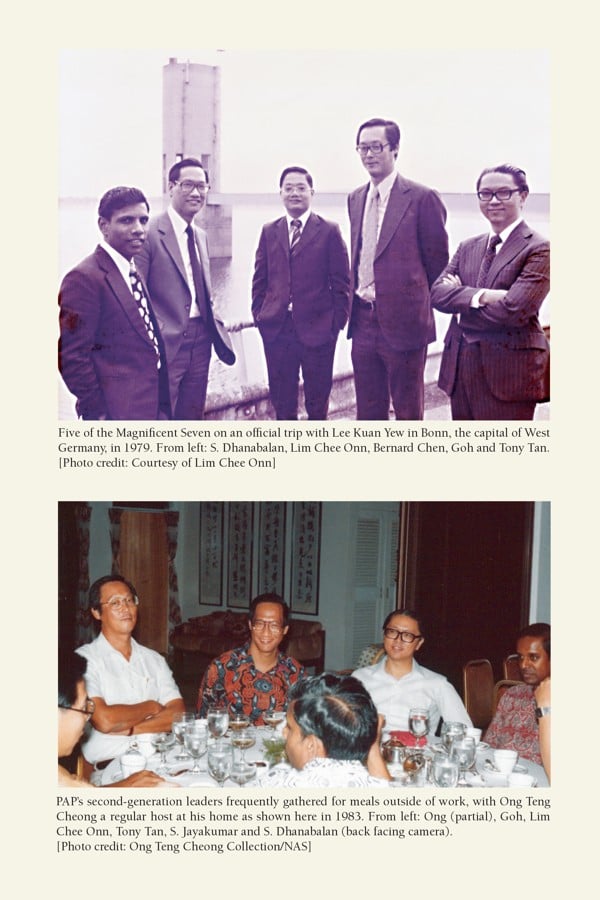

Goh was in the batch of technocrats inducted by Lee, who was then obsessed with renewing the ranks of the political leadership, including by purging comrades he had fought alongside to secure Singapore’s independence, much to some colleagues’ unhappiness. They were still in their 50s and early 60s and wanted the next generation to be blooded the way they had been, not handed top positions on a platter.

Goh says the older leaders often lamented that his batch, the second-generation leaders, lacked “fire in their belly”.

“Then over time, it came. Small spark, ember, as we got into the job, as Lee Kuan Yew and the team got older,” he says.

That ember grew into fire to serve, he says, when it dawned on them the task of keeping the Singapore project going was fully theirs to shoulder.

FATHER, SON, HOLY GOH

Throughout, Lee was ever-present, steering and shepherding the young Turk-nocrats.

Lee as mentor was proper, formal and kept to protocol, says Goh. When he stepped aside, he only gave his advice but did not make the decisions. He seeded ideas but left his successors to tend to their final fruition. But Lee the kung fu master was something else. He gave Goh and his peers “lashings”, the lead disciple recounts, almost with the relish of a schoolboy recalling corporal punishment.

“I accepted his lashings. I never answered back. I just tried to improve. There was nothing personal. It was a relationship between a master and a disciple. I was determined to succeed as his disciple. He saw strengths in me.”

In the book, Goh opens up on the two public occasions he was subjected to such humiliating verbal assaults. A third occasion – never before revealed – is recounted by a former colleague.

In interviews with foreign media in early 1987, Lee said he was setting 1988 as his target year to step aside so he would force the pace of renewal and get younger men to take over. By then, it was widely known that Goh was the successor and de facto prime minister – playing the role of CEO while Lee was chairman, is how Goh puts it in the book.

But at his 1988 National Day Rally, usually the most important platform to address the nation, Lee was silent on the date for succession. Instead, he handed out a frank assessment of the technocrat successors.

He said that even though Goh had the “faster mind, a quick brain” among them, Goh was not his first choice for successor. Goh spent too much time trying to please everyone, he said.

Why Singapore won’t be repeating Malaysia’s political dramas any time soon

Goh was in the front row in the audience. In the book, Goh said: “I was perplexed, stunned, dumbfounded by his revelation. You have to live with the awkwardness of facing the big crowd after the rally. You had to be very wooden when you came out.”

The word “wooden” was a funny dig and a segue to Lee’s second critique of Goh a week later. Lee told an aghast audience he found Goh too wooden and that he ought to see a psychiatrist.

Goh was upset not by the wooden adjective flung at him – even though it came wrapped in the velvet glove of praise, it must be noted – but the advice to consult a psychiatrist. But as with the first episode, he “just shrugged it off”.

The two incidents, however, were an epiphany for Goh. The humiliations liberated him from the burden of trying to match up to Lee.

As he said at a forum soon after: “Do not be too upset or confused by the PM’s remarks about me. Take me for what I am. There is not going to be any change in leadership after the prime minister has eventually relinquished his position. The second generation leaders have decided and that’s that.”

The third put-down was in the midst of the government’s dealing with so-called Marxist conspirators in 1988. While in detention, they had confessed to being Marxists, but recanted when they were released. Lee was out of the country and Goh, as acting prime minister, was deemed by Lee to have been too slow to crack down on them.

At a cabinet meeting later, Lee revealed his unhappiness at not being able to get through to Goh at home during the incident – it was found out later that Goh’s son was using the telephone. According to then Environment Minister Ahmad Mattar, Lee turned to Goh and remarked angrily: “If Loong was not my son, I would have asked him to take over from you now.”

Loong, who was in the cabinet at the time of the comment, is now Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. Goh says he has shown Loong his book, and that the prime minister asked him if he was sure he wanted to retain this passage. Both decided they could live with it. After all, this would not be the first time – nor the last – the complex relationship among the three would come under a microscope.

We ask Goh how he felt about that last “lashing”. “It’s not like a romantic break-up where one would sob and bury his head, and years later recall with bittersweetness the pain in his heart. I simply sat still and, to borrow LKY’s word, put on a ‘wooden’ or an impassive face.”

He did not look around either to see how others felt, he says, but he could well imagine their embarrassment. Lee Kuan Yew had by then taught them a lesson in being rebuked publicly at his very first sitting in parliament, he recalls. Then, Lee conducted a three-hour tutorial on leadership and tore into a former MP, a doctorate holder in economics, dismissing him as someone with six cylinders but only two firing.

Will Singapore’s politics change as its parties shift to Gen Next?

Goh shrugs off the public takedowns as lessons that made him the leader he is. The complete trust he had in Lee made him feel no malice was ever intended. Lee was also not doing so to burnish his own son’s credentials. Neither was Lee Hsien Loong above being challenged by his father, says Goh. But it does occur to Goh that the two public humiliations were meant to signal to him and perhaps the public that he was not ready and therefore Lee was not prepared to step down as prime minister.

The book thus reveals for the first time that it was Lee who asked Goh if he could stay on as prime minister for another two years. Goh assented.

Goh says he was relieved. A lifelong tennis player, he knew he was not ready. “Would you go into a tournament, like tennis, when you have not yet peaked? I was quite happy. But after two more years, in my heart, I felt I was ready.”

During that same 1988 speech, Lee revealed his own anxieties about stepping down when he said: “Those who believe that when I have left the government as PM that I have gone into permanent retirement, really should have their heads examined.”

BETWEEN THE LEES

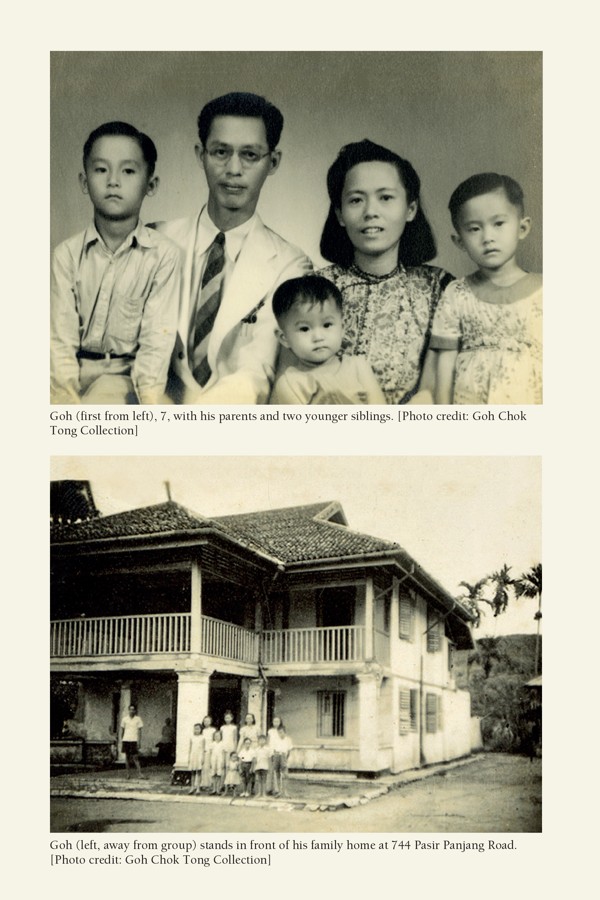

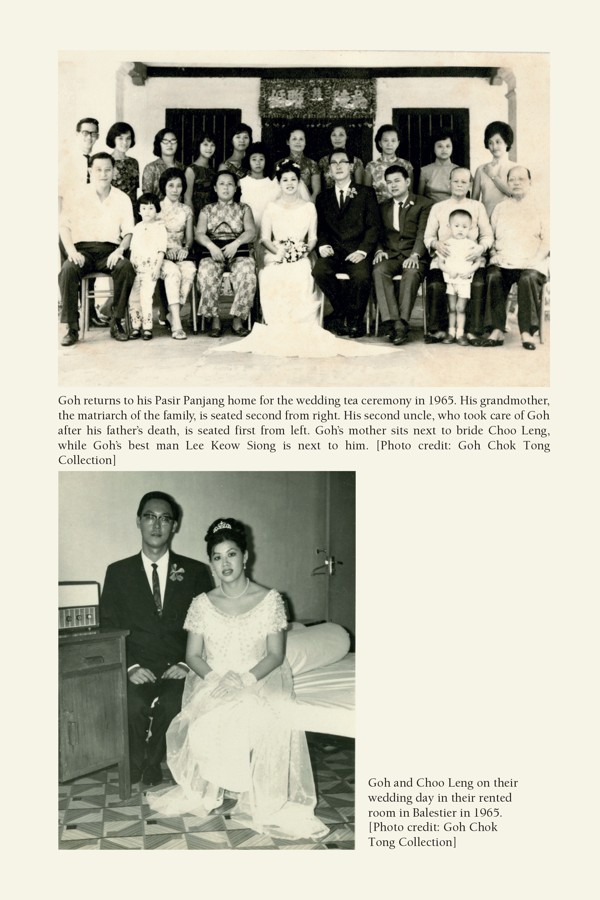

Goh’s philosophical – some might say resigned – attitude could have arisen from having learned the vicissitudes of life at a young age. He lost his father at the age of 10 and then had to live apart from his Chinese-schoolteacher mother, who left him with family when she took up residence in her school quarters.

Although there were times his status seemed tenuous, he was not afraid of inducting talent, as he and others around him have said. In the book, Goh goes to some lengths to show it was he who identified Lee Hsien Loong as a political candidate. It was he who sought him out, not Lee Kuan Yew who asked him. Goh showed the file on Lee Hsien Loong the aspiring politician to the author of the book. Lee Hsien Loong had to produce references and go through two rounds of interviews, each lasting an hour and a half.

“This is to show you that the way we work is not at Lee Kuan Yew’s whim and fancy. It is very systematic. Look, Lee Hsien Loong had to submit his CV. Chinese – C4, so he was not straight As! There were people who were better than him, all A1s, but when I interviewed them, they were not very good,” Goh says in the book.

Goh tells us that Lee Kuan Yew had always felt his son had the qualities to be the next prime minister. He told his fellow Old Guard leaders several times. But he knew he could not do so immediately after him.

“It would be perceived as dynastic politics. That would be bad for Singapore. It would also undermine Lee Hsien Loong as people would conclude that he was put there because he was the son of Lee Kuan Yew, and not on his own merit.

“Toh Chin Chye and Ong Pang Boon spoke up openly against Lee Hsien Loong succeeding him. It was a conundrum for Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP.” Toh and Ong were Old Guard leaders.

Goh reduces all questions on this political triptych with him in between the two Lees to one word – trust.

“Over the years, the trust was built up and also my judgment of him and I think I was right in retrospect. Had I come to the conclusion I was merely being used by him, whether it’s for two years, three years or 14 years for Lee Hsien Loong, that’s a different matter,” Goh says of his mentor-cum-kung fu master Lee.

Goh reveals that Hsien Loong was not the only child of Lee whom he considered for political induction. Hsien Yang, Loong’s estranged younger brother, was not recommended by Lee Kuan Yew, who said in his own book Hard Truths that his second son never showed an interest. Goh says he thought of Hsien Yang but did not pursue the matter because “I think he would be outshone by his brother”.

Curiously, Goh reveals that Lee Kuan Yew did suggest that his only daughter, middle child Wei Ling, could be considered as a potential Member of Parliament – but this was a recommendation made in response to Goh’s search for women candidates. Goh consulted with foreign affairs minister George Yeo, who said no, and her own brother Hsien Loong, who also said no. And that was that.

Who’s who in the Lee Kuan Yew family feud

Asked if this revelation would make things awkward among the siblings, who have not spoken to each other recently because of a property dispute over their childhood home, Goh says: “I do not think this revelation can make the awkward situation in the family any more awkward.” On Hsien Yang, Goh expands: “I was very careful. I didn’t put in a third Lee. I considered him. I wanted to have the best people … But three Lees would be a bit too much.”

“Four Lees, then I might as well give up,” he says, as the room erupts into laughter. “It’s true, it went through my mind. Hsien Yang, even though he would be suitable for his commercial experience, I think I cannot. I cannot carry the public with me. How can you be your own man when you have so many Lees there …”

For a split second, we pause at the idea of such a cabinet and then the room melts into laughter again as Goh adds: “ … and not forgetting Lee Yock Suan as well.”

Lee Yock Suan is no relative of the Lees but was in cabinet in Goh’s time. His son, Desmond Lee, is now in cabinet serving under Lee Hsien Loong.

‘THIS IS ME’

Throughout the book and during the interview Goh is unabashed about who he is. We ask him and he says it is hard for him to analyse himself because he learned early in life a person has three selves – who he thinks he is, what others think he is and who he really is.

“You will never know who you are,” he says.

That reluctance to claim who he is feeds into another unexamined aspect of Goh – his capacity for understatement. He admits he does not feel the need to assert himself. “Don’t talk about your achievements. Recognise your deficiencies, don’t try to hide them.”

The first volume of his biography, however, does list out Goh’s achievements during his years of an understudy to Lee Kuan Yew. Many of the policies of the late 1980s and 1990s were given shape and substance by Goh’s team. Medisave, a critical savings scheme to inject personal responsibility in to health care consumption, is chief among them. Others include the move to instil market discipline in government, whether it be for health or housing and the way land acquisition is compensated. These moves to introduce discipline to government operations and set up accountable systems were underappreciated shifts undertaken by the second generation leadership, he says.

Goh has no trouble admitting Lee gave them many ideas (including one about allowing a nudist colony to attract tourists that made his younger colleagues squirm). But every idea, he says, had to be debated and approved by cabinet. The cabinet worked as one team. “We did not claim individual credit.”

As to the restraining influence Lee had in his cabinet when he was prime minister, Goh quips we will have wait for the planned second volume. If anything though, Goh is adroit enough to admit this: “Better to have Lee Kuan Yew inside than outside because inside he was a member of the cabinet subjected to collective decision.” He laughs again.

“So it’s the comfort level. Because having worked with him for quite some years, knowing his style and my own personality was such that we could click.”

During his years in office, Goh spent considerable time growing Singapore’s external wing – taking companies overseas, making a mark for himself such that once his name was even floated as a potential United Nations secretary general.

His preoccupations these days are to think about over-the-horizon issues and he worries about social mobility and class divide, meritocracy and its negative tail effects. He raises funds for charity, including the most recent effort so far, which is the book – all royalties from its sale will be donated. Already, S$1 million (US$724,000) has been raised. He is also senior adviser to the Monetary Authority of Singapore and chairman of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s governing board.

Despite his easy-going ways, Goh, who blogs on his MParader Facebook account, gets into a pickle every once in a while for his candour – telling things the way he sees them, a trait no doubt picked up from his predecessor. Earlier this year, when he commented on the need for clarity on political succession, Lee Hsien Loong and the younger leaders gave a miffed response, saying they would decide at their own pace. Then, not too long ago, he picked up the permanently hot-potato subject of high ministerial pay – almost all who touch it get burned.

Why the Lee Kuan Yew family feud is a metaphor for Singapore

Goh was quoted as saying if cabinet was made up of those who could only earn half a million dollars instead of able men and women earning five million dollars, it would be filled with mediocre people. It created a ruckus as people took umbrage at the “mediocre” jibe. He concedes he could have explained better. He had meant to say no effort should be spared to get the best into cabinet to lead the country, including those from the well-paid private sector. Otherwise, cabinet would comprise mainly former public officials and Singapore Armed Forces officers, thus lacking in diversity.

But he says he stands by his statement that “cabinet will be mediocre” if top talent – as measured by the market – is not recruited. “I’m prepared to defend this,” he says.

It is like getting the best lawyer to defend you, he goes on. And as with many other bumps along the way, Goh is implacably calm.

If Lee Kuan Yew as the first prime minister fought epic battles, faced down danger and stared death in the eye to prevail, Goh as the successor had only one thing to prove – that the system could survive Lee.

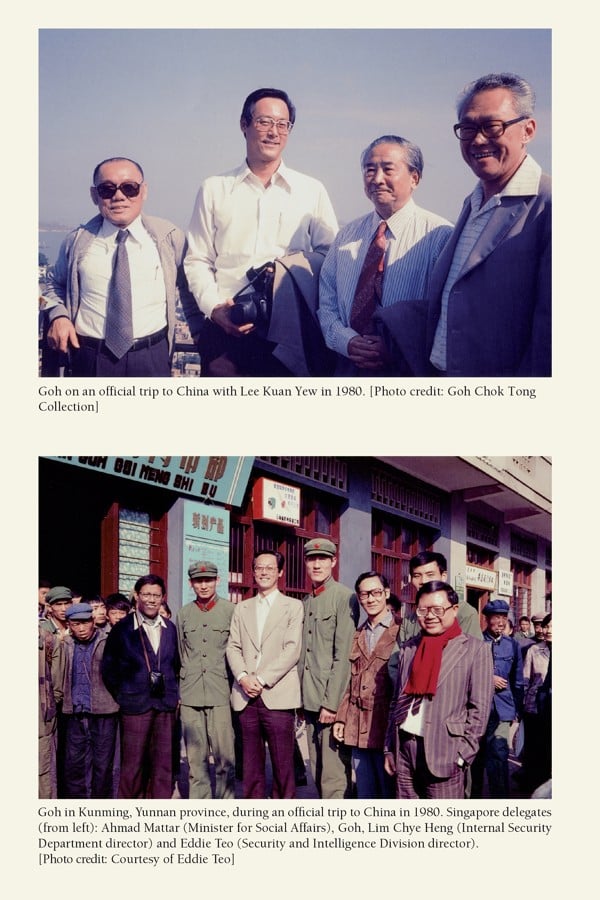

He puts it this way: “I did what I did out of a sense of duty. And despite all the difficulties and all the weaknesses I had to be a political leader, I soldiered on out of a sense of duty.” ■