Deportation and detention: 3 million face statelessness in Assam

- More than three million people are at risk of being left stateless in India’s northeastern state of Assam in a crisis that is being compared to the plight of the Rohingya in Myanmar

More than three million people are facing statelessness in India’s northeast, with minority Bengali Muslims and Hindus fearing deportation and detention, in a crisis that is being compared to the plight of the Rohingya in Myanmar.

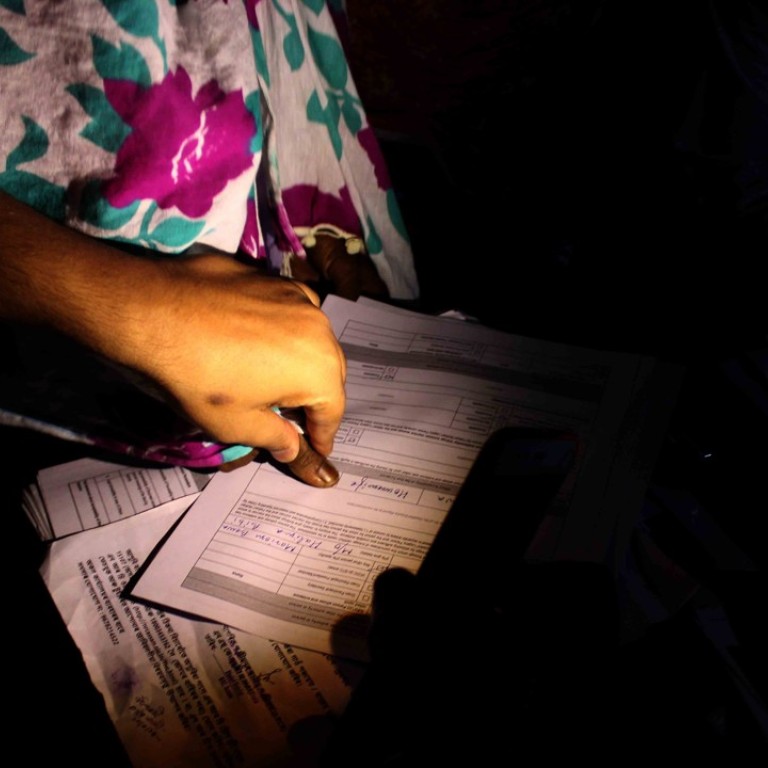

With a December 15 deadline for inclusion in Assam state’s National Register of Citizens (NRC) fast approaching, about three and a half million Bengali Hindus and Muslims could be left without citizenship as they lack documentary evidence for their claims.

The register is being updated as part of the Indian government’s efforts to clamp down on illegal immigration from Bangladesh, following an explosion in anti-migrant sentiment in the border state of Assam.

Although the Hindu nationalist government has said that Hindu migrants from Bangladesh should be protected, it has called for the expulsion of Muslims who are found to be illegal.

Under an amendment proposed by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, citizenship would be granted only to Hindus and other non-Muslim minorities who migrated from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The bill, which is before a joint parliamentary committee, has provoked an intense backlash in Assam, where many residents want to expel all illegal migrants from Bangladesh, regardless of their religious affiliation.

Police and intelligence officials say dozens of young Assamese have joined the separatist United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) in anger, upset with the proposed amendment.

Six months after Trump and Kim shook hands, denuclearisation a distant hope

“The ULFA was down and out, but now it seems to getting a fresh lease of life,” said Subir Dutta, a former Intelligence Bureau official who served in Assam.

During a rally against the bill last month, protesters burned effigies of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Assam Chief Minister Sarbananda Sonowal, who had enjoyed huge popularity for leading anti-migrant movements as a youth leader.

“The BJP is trying to dilute our victory in the battle against illegal migration by bringing this constitutional amendment. We will face police bullets but not allow this to happen,” said Akhil Gogoi, the leader of a 70-group coalition against the bill.

The crisis follows a Supreme Court ruling in 2014 that ordered for the NRC to be updated, following a petition by an Assam-based non-profit organisation.

Nearly 33 million people applied for inclusion on the NRC, but just over four million of these – mostly Bengali Hindus and Muslims – were asked to file additional documentation to support their claims.

“But with more than three million yet to file claims and hardly much time left, it looks like around three million people will not ultimately make it into the NRC,” said a Ministry of Home Affairs bureaucrat on condition of anonymity.

Hafiz Rashid Ahmed Chowdhury, a lawyer and Bengali Muslim who represents ethnic minorities, said that the state’s ethnic Assamese-dominated bureaucracy appeared determined to deny citizenship to as many people from minority communities as possible.

“They make things as difficult as possible for the minorities,” he said. “The procedures are also complicated, especially in matters of legacy data. So most of those excluded have not been able to file claims.

“On the other hand, local groups often acting as vigilantes have filed objections against many who have been included, alleging they used fake documents.”

More than twenty Bengali Hindus and Muslims have committed suicide after their exclusion from the NRC, unable to cope with an uncertain future.

“They felt humiliated and were apprehensive of spending the rest of their lives in detention camps,” said Uttam Saha, a journalist in Assam who has spoken to families of those who have taken their own lives.

“Thousands of families are facing ruin, spending hard-earned money on lawyers or for bribing officials,” Saha said.

The NRC is unique to Assam, where it was established in 1950 immediately after India’s independence.

Don’t ask why US acted against China’s Huawei. Ask: why now?

But there is some confusion as the Election Commission of India has said those left out of the NRC will not be automatically disenfranchised and could still be included on the electoral roll if they produced authentic documents to prove citizenship.

The Indian government has set up a committee to examine what to do with those who will be excluded from the NRC.

“That’s a huge population running the risk of becoming stateless and losing citizenship,” said Ranabir Sammadar, a migration expert at the Calcutta Research Group (CRG). “They have lived in Assam for decades, most of them own property and have integrated into Assamese society. To now deny them citizenship will create a huge humanitarian crisis.”

CRG director Anita Sengupta compared the situation to that of the Rohingya.

“This is looking like the crisis faced by Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar’s Rakhine province,” she said. “If it affects the whole of India’s northeast, things could get worse.”

The scion of Tripura’s former ruling royal family, Pradyot Kishore Manikya, has petitioned the Supreme Court to extend the process to Tripura where Bengali migrants now outnumber indigenous tribespeople.

The BJP has called for the NRC to be updated in West Bengal and other states affected by migration from Bangladesh, with party chief Amit Shah likening the illegal migrants to “termites”.

The BJP government has however assured an apprehensive Bangladeshi government that updating the NRC was “an internal exercise” and no one will be forcibly returned to the neighbouring country.

“But this surely has an adverse impact on India-Bangladesh relations,” said Bangladesh watcher Sukharanjan Dasgupta. “The shrill rhetoric is incompatible with our otherwise very friendly relations.”

Bangladesh’s ruling Awami League, a secular party, is believed to be concerned that repatriations would hamper its chances in upcoming elections on December 30. The Islamist opposition has accused the Awami League of being an Indian surrogate and not strong enough to stand up for the national interest.