Indonesia election: hardline Islam, where it all went wrong for Prabowo Subianto

- Yohanes Sulaiman charts the course to Wednesday’s turbulent election day, and what the likely takeaways will be

- For Prabowo, it is not due to lack of trying. Pollsters say he won the popular vote in four more provinces this year compared to 2014

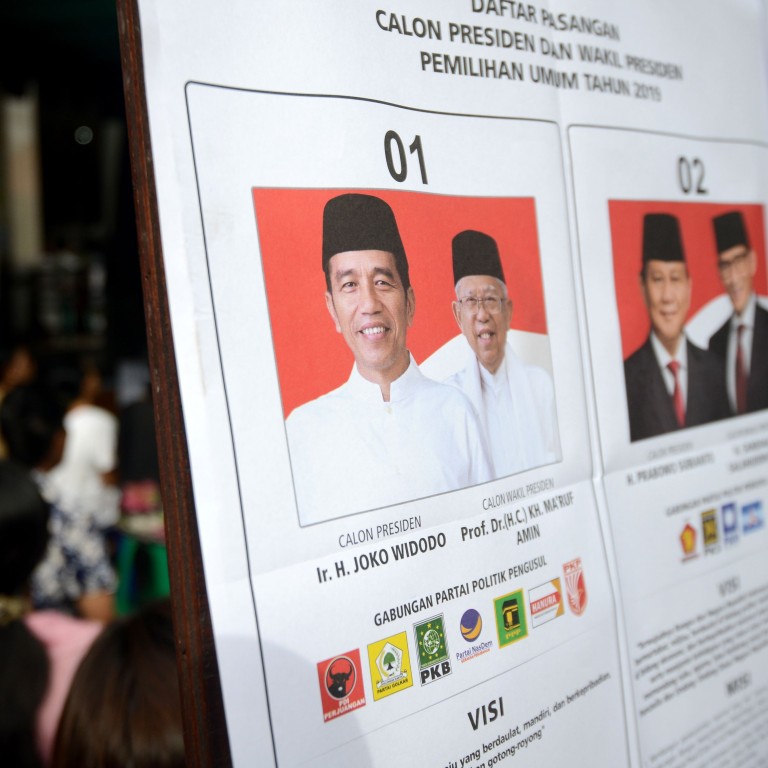

For pollsters tracking both candidates over the last eight months, the outcome is not a surprise. Indikator, IndoBarometer, CSIS, Kompas, and Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting (SMRC) had predicted Jokowi and his running mate Ma’ruf Amin’s victory albeit with a wider margin of victory.

For Prabowo, it is not due to lack of trying. Pollsters say the former general won the popular vote in four more provinces this year compared to 2014, though official results from the Indonesia’s Elections Commission are not yet out and might only be released in May.

Prabowo disputes quick count results to claim victory over Jokowi

These 14 provinces – expected to include West Java, Banten and North Sumatra – are known to be among the most conservative places in the country. Since the 2014 election, Prabowo’s supporters have painted Jokowi as an enemy of Islam, a secret Communist and a Catholic, despite the incumbent leader being a devout Javanese Muslim. Their efforts to discredit Jokowi’s policies have tapped into latent anti-Chinese sentiment, and this line of attack hit its crescendo in 2017.

Jokowi however was on alert and realising he might lose his bid for a second term, decided to safeguard himself by giving favours to Indonesia’s largest Muslim organisation Nahdlatul Ulama (NU).

Jokowi also benefited from the Islamists overplaying their hands. Moderate and minority voters had been crestfallen when Jokowi chose Ma’ruf – who was instrumental in bringing down Ahok and once forbade Muslims to say “Merry Christmas” to Christians – and felt let down by his lack of attention to human rights problems. They may have thought to skip the election but finally decided to hold their collective noses and vote for Jokowi, resulting in the spectre of a low turnout or high numbers of spoilt ballots – which would have worked in Prabowo’s favour – not materialising.

Of the 192 million registered voters, about 80 per cent went to more than 800,000 polling stations to punch their ballot cards, probably worried that their inaction would result in a Prabowo victory and a clampdown on their rights.

Youth voters, short-lived golput fears: 5 takeaways from Indonesian election

The campaign period has given Sandiaga nationwide recognition and if Prabowo bows out from politics, the former could easily take over the reins of Gerindra, Prabowo’s party that is likely to be the second-largest in Parliament.

Debt fears, delays: is China’s rail plan for Indonesia off track?

Sandiaga benefited from the support of Islamists but never hoisted their flag on his mast, choosing instead to portray himself as a pious though tolerant and moderate Muslim. His focus on the economy means he will still have some appeal to voters, opening the door to another contest.

Still, what Jokowi’s likely victory shows though is that they can still be beaten, if a coalition of moderates can be motivated to come together and negate the issue of religion in elections. This is the lesson of the 2019 presidential election.

Yohanes Sulaiman is a lecturer in International Relations at the School of Government at the Universitas Jenderal Achmad Yani in Cimahi, Indonesia