Pakistan’s new Kashmir map links it to China, fuelling India’s fears of war with both

- On paper, the map links Pakistan with Chinese-administered territory and hints at the possibility of coordinated military operations between the two

- Little evidence exists that such a conflict is in the works, however, and analysts caution the map is driven more by domestic politics

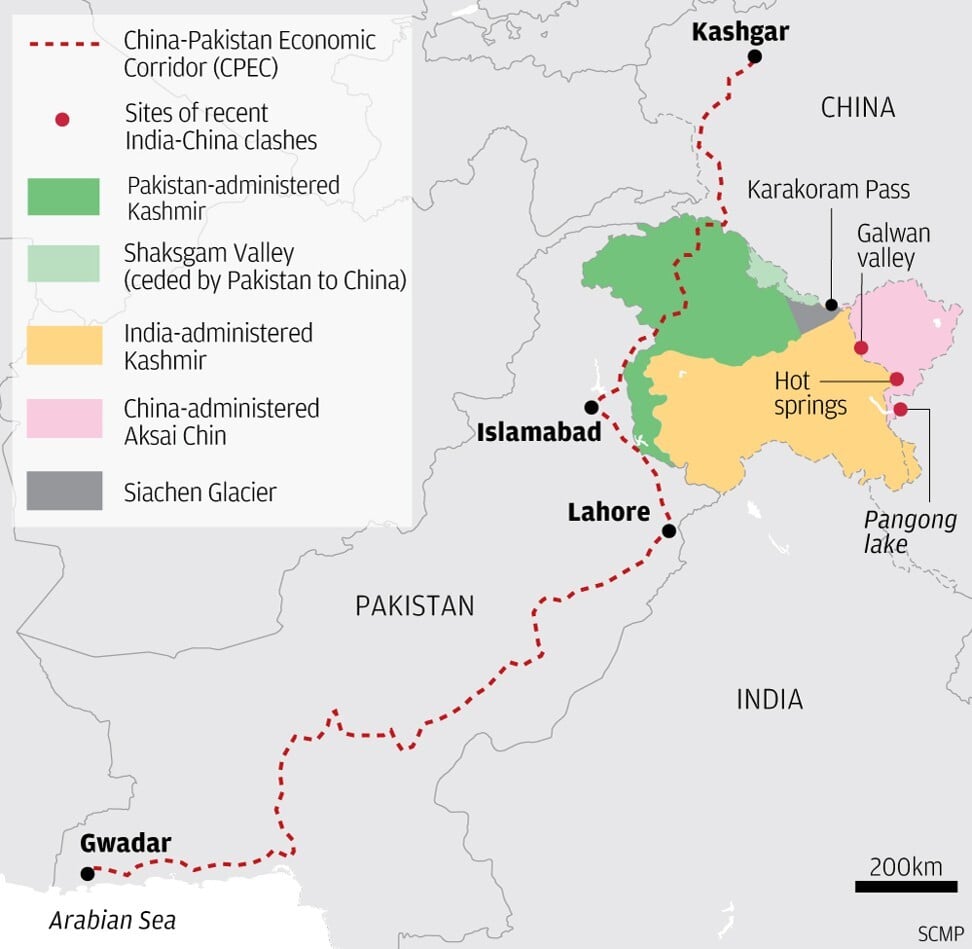

On paper, the map links Pakistan with Chinese-administered territory via the Shaksgam Valley, a part of the Gilgit-Baltistan region ceded to China by Pakistan under their 1963 border settlement. To the east is the Aksai Chin region – the limit of China’s claims in Kashmir which it has controlled since a 1962 war with India.

Between the two lies the Siachen Glacier, an undefined area at the northern extreme of the de facto border between Pakistani- and Indian-administered Kashmir known as the Line of Control – not to be confused with the Line of Actual Control, which separates Indian- and Chinese-controlled territory in the region.

India, like Pakistan, claims Kashmir in its entirety and has no interest in pursuing a United Nations-supervised plebiscite, supported by Islamabad, for the region’s residents to decide which country they should join.

To this extent, Pakistan’s new map does hint at the possibility of coordinated operations with China if Islamabad ever attempts to forcibly take the glacier, which would create a land bridge between Gilgit-Baltistan and Chinese-administered Aksai Chin.

Since Chinese and Indian forces clashed in the Ladakh region this summer, Indian media have speculated about China’s strategic intentions in the area, including the possibility of it seeking to seize territory – fuelling fears of a future war with both China and Pakistan.

“This certainly reinforces the Indian perception of a two-front theatre that its military planners are increasingly taking into account,” said Harsh V. Pant, a professor of international relations at King’s College London.

This [map] is presumably meant to be a defence of the Belt and Road Initiative, which India opposes because it runs through disputed territory that it claims

Michael Kugelman, senior South Asia associate at the Washington-based Wilson Centre think tank, said the strategic value of Pakistan’s new map, for Beijing, may lie in the additional political cover it provides to belt and road projects being built in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan.

In June, Pakistan awarded contracts for the construction of three major hydropower projects along the Neelum River to Chinese state-owned enterprises under the CPEC programme.

The Neelum River marks the divide between Indian- and Pakistani-administered territory in western Kashmir, before it merges with the Jhelum River, a major tributary of the Indus. This in turn supplies water from Himalayan glaciers to an estimated 270 million people in Pakistan and northwest India.

Asma Khan Lone, author of an upcoming book on the history and the geopolitics of the region called The Great Gilgit Game, drew a parallel between Pakistan’s new cartographic claim to the Indian-held Siachen Glacier – a huge source of fresh water – and China’s efforts to “weaponise water” in Ladakh by building dykes for what she described as “tactical flooding”.

Previously vacant because of its extreme altitude, the Siachen Glacier was occupied by Indian forces in 1984, prompting years of intermittent fighting between India and Pakistan at an average elevation of more than 5,400 metres above sea level until a ceasefire was agreed in 2003. The glacier is notorious for killing far more soldiers with its extreme environment than enemy artillery shells ever did: in April 2012, 129 soldiers and 11 civilian contractors were killed after an avalanche buried a Pakistani military base in the nearby Gayari sector.

The huge cost of waging war on the glacier, both in terms of finances and human lives, has so far prevented skirmishes breaking out there in the same way they have done elsewhere along the Line of Control since 2016.

But tensions are on the rise. In February last year, Indian warplanes crossed into Pakistani air space near the glacier. Delhi has also recently started reasserting its claims to Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan and Kashmir by including both in the country’s official weather forecasts since May, while Indian military chiefs have declared their forces ready to seize the territory if so ordered.

Kugelman of the Wilson Centre said Pakistan’s new political map is “presumably meant to push back” against such threats – but like India’s bombast, he said it is driven more by domestic politics than long term strategic plans.

“I don’t think we should read too much into this map,” he said. “It is just the latest subcontinental case of using cartography to appeal to nationalism at home, while taking a shot at the enemy next door.”

‘Can China help?’ In Kashmir, anti-India militancy continues

Zhou Rong, a senior fellow at Renmin University’s Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies who has researched Pakistan and Afghanistan, said the risk of a fourth war between Delhi and Islamabad over Kashmir was very real.

“India also realises that ties between Pakistan and the US has become less important over the years, and that Washington has stood on its side during its conflicts with Pakistan,” he said. “This has enabled India to become even more confident.”

He added that “many countries are unwilling to offend India” as they are “increasingly reliant” on it economically. “Many traditionally Islamic countries have also forged better relationships with [New] Delhi, seeing it as an important market for their energy exports,” he said.

Additional reporting by Maria Siow