Censorship, sedition probes: is Perikatan Nasional’s Malaysia ‘sliding down the democracy scale’?

- Rights groups warn the government is backtracking on the progress made under its predecessor, the Pakatan Harapan

- Sedition investigations have tripled, while repressive laws and the harassment of journalists are being used to stifle dissent, critics say

Observers say the Perikatan Nasional coalition government has taken a marked turn from the approach of its predecessor, the more permissive Pakatan Harapan, which was voted into power in May 2018 but unceremoniously turfed out in a political coup in February this year.

His remarks follow a decision by parliament last week not to discuss an annual report by Suhakam that had called for greater protections for indigenous peoples, women and children, victims of human trafficking and refugees. Parliament, currently engaged in vociferous debate on the 2021 federal budget, cited more pressing issues.

But Joseph said the silence on the report was just one of the concerns facing human rights in the country.

“The shying away from a bill on an independent police complaints commission, the shunning of a National Harmony Commission and the shelving of open debate on the Suhakam annual report is indicative of the regression of hope on human rights matters that Malaysians were looking forward to,” said Joseph.

In May, Minister of Home Affairs Hamzah Zainudin said the government had initiated 262 sedition investigations in 2020, up from 78 in 2019 and 31 in 2018.

Similarly, in the first six months of 2020 there were 143 investigations under the country’s broad Communications and Multimedia Act, compared to just 47 in the 13-month period from the beginning of 2018 to February 2019.

“Attacks on the right to freedom of expression are once again rising in Malaysia. Repressive laws are still on the books, and more and more people are coming under police investigation simply for speaking their minds,” said Katrina Jorene Maliamauv, Executive Director of Amnesty International Malaysia.

Is Malaysia’s new government using Najib’s old playbook to stifle dissent?

In response, her organisation has launched a campaign called Unsilenced to resist the government’s use of what it says are repressive laws such as the Sedition Act, parts of the Communications & Multimedia Act, and the Printing Presses & Publications Act. The campaign features a gallery of items censored or banned in Malaysia.

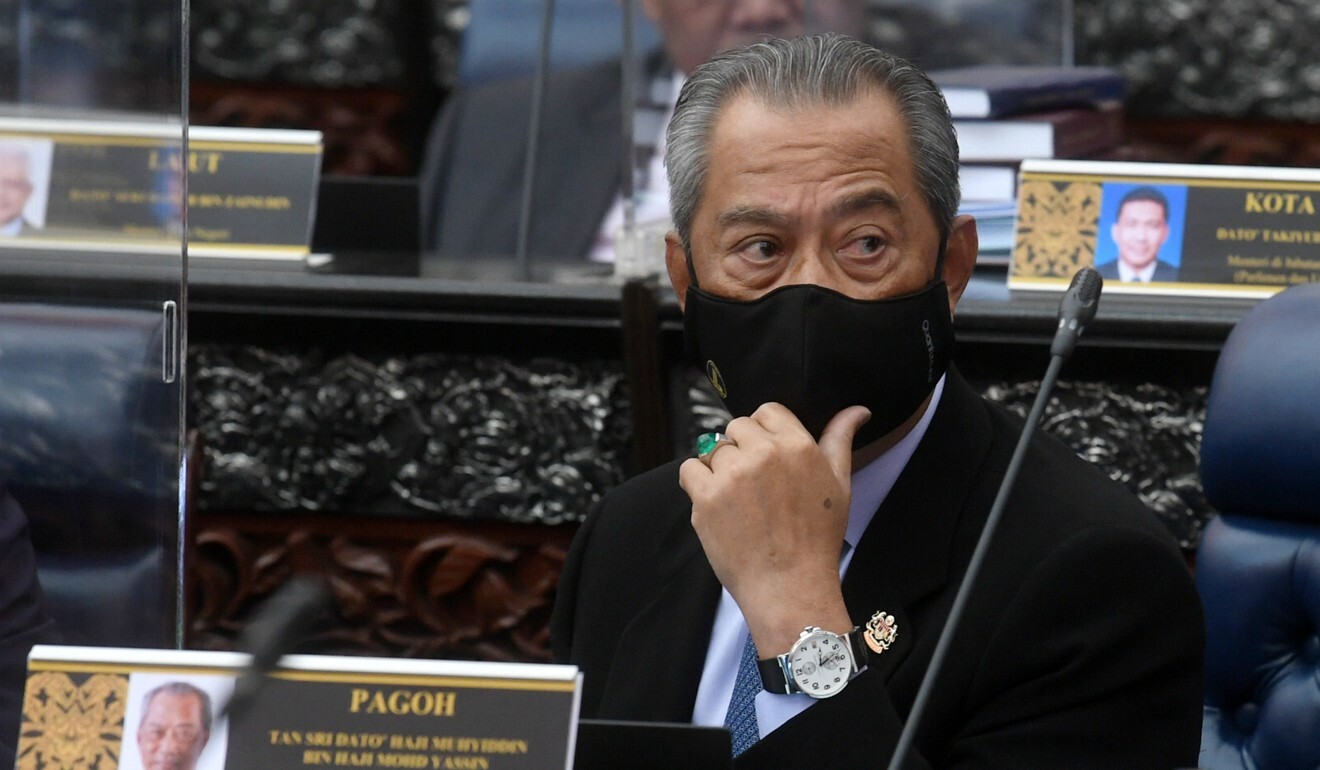

The government’s messaging in the face of the coronavirus pandemic has been to portray itself as caring – Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin has referred to himself several times as “abah”, a fond term for “father” – but this has come in for criticism.

Amnesty International Malaysia and many domestic and international organisations have been raising the alarm on the decline in freedom of expression in 2020

“It sits in contradiction to arrests, investigations and questioning of citizens, migrants, activists, journalists and opposition leaders who report on or express viewpoints the administration may feel are unfavourable to them. Amnesty International Malaysia and many domestic and international organisations have been raising the alarm on the decline in freedom of expression in 2020.

“There has not been any indication, however, that the government is going to slow down its use of these laws that silence people in Malaysia, let alone reforming them,” Jorene Maliamauv said.

05:32

Malaysia’s ex-PM says Muslims ‘have right to kill millions of French’ hours after France attack

The government has defended its use of these laws, calling them necessary for domestic peace and harmony. In a recent parliamentary response, the Home Ministry said it had no intention of repealing laws such as the Sedition Act, describing it as a “deterrent” to ensure Malaysians did not “ridicule issues that may be sensitive”.

“Comments on these sensitive issues, if not curbed, can affect the peace and harmony of Malaysians,” it said.

In a report this week, the international civil society alliance Civicus said around 90 per cent of countries in Asia restricted civic freedoms. It classified liberties in Malaysia as “obstructed” due to prosecutions of people who criticised the monarchy and the harassment of journalists and activists.

Clamping down on avenues for dissent could hurt the nationalist Perikatan Nasional at the ballot box come the next general election, political scientist Wong Chin Huat warned.

“If Pakatan Harapan gets its act together, young and middle-upper [class] voters – regardless of ethnicity – may punish Perikatan Nasional for this,” he said.

“The crackdowns can be seen as a return to a time before the 2018 elections, especially when many old guards of the former Barisan Nasional regime are now in the current government. Malaysia will further slide down the democracy scale.

“The silver lining in the current situation now is that we don’t see a polarisation similar to what we have seen in the past. The conflict line is not neatly drawn between Perikatan Nasional and Pakatan Harapan. There are cracks within the ranks of political elites that makes uniform crackdowns much harder to carry out.”

In May, a 73-year-old radio announcer was arrested on suspicion of insulting the crown prince of the state of Johor on Facebook. Activists said this was another instance of police abusing the country’s laws.

In July, the government launched police investigations into Al Jazeera journalists working on a documentary about the conditions migrant workers faced under lockdown and threatened to cancel the channel’s accreditation.

Hundreds arrested as Malaysia cracks down on migrants in Covid-19 red zones

In the same month, the editor of news website Malaysiakini was charged for contempt of court over five comments posted by readers that were allegedly critical of Malaysia’s judiciary; a refugee rights activist was questioned by the police for highlighting the conditions in immigration detention centres; and a retiree was fined two thousand ringgit (US$490) for “insulting” the Health Minister on Facebook despite courts accepting the criticism was not malicious in nature.

In November, the police investigated a student organisation after it posted an article on social media commenting on the role of the king in a constitutional monarchy, later charging an activist for filming a police raid.

It’s unclear whether such actions will affect the recent gains Malaysia has made in the annual Reporters Without Borders press freedom index. In 2018, Malaysia was ranked 145th. In 2019 it rose to 123 and in 2020 was 101. The 2020 report was released just two months after the political coup.

Commenting on the jump in April, Reporters Without Borders said Malaysia showed the greatest improvement, confirming the “dramatic effect that a change of government through the polls can have in improving the environment for journalists and combating self-censorship”.