Advertisement

India-China relations: Modi, Xi look set to meet. Will frosty ties thaw at BRICS, G20 summits?

- Modi and Xi have not had an in-person meeting since 2019 and the ongoing border dispute has only served to inflame tensions

- The Chinese president’s presence at India’s G20 summit will speak volumes, but analysts warn that ties will not improve noticeably in the short term

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

10

Within months, both Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping are likely to be in the same room again.

But whether the two leaders will hold bilateral talks and seek to mend their countries’ deeply strained ties remains to be seen.

Doubtful Indian foreign-policy observers cite New Delhi’s last-minute decision to make this month’s Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit virtual, eliminating the chance for a Modi-Xi meeting on the sidelines.

Both leaders are set to attend the BRICS Summit in Johannesburg from August 22-24 and the G20 Leaders’ Summit in Delhi a fortnight afterwards.

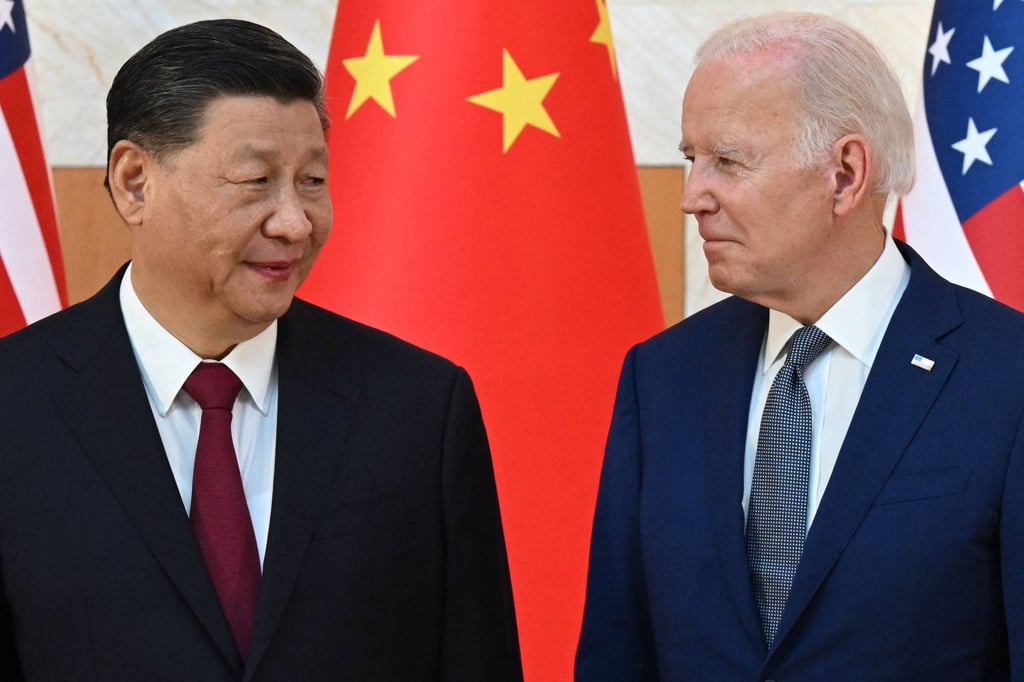

Yet Modi and Xi have not engaged each other diplomatically since the 2019 BRICS summit in Brazil. By contrast, despite deeply strained ties, Xi has met US President Joe Biden twice over the last two years, with a third meeting seemingly in the works.

A meeting between Modi and Xi is growing ever more essential, analysts say, amid their ongoing border stand-off and diplomatic flare-ups that have only hardened attitudes even as both nuclear-armed neighbours continue to fortify the Line of Actual Control with troops, heavy artillery and infrastructure, including lightweight high-altitude tanks.

Advertisement