China-friendly Laos faces pressure to prioritise Asean’s interests on South China Sea, Myanmar

- There are concerns Laos, which has hooked its economic fortunes to Beijing, will ‘do China’s bidding’ as the new Asean chair

- But analysts say Asean member states are likely to influence the country to promote the ‘regional interest’ over issues such as the South China Sea and Myanmar

Will untested Laos affect ‘unity in Asean’ over Myanmar crisis, South China Sea?

Although Marcos Jnr eventually clarified that he did not endorse Taiwan’s independence and remained committed to the one-China policy, the incident sparked a heated exchange between officials from both countries, adding to the existing diplomatic strain.

Under Beijing’s one-China principle, Taiwan is a breakaway province to be eventually reunited, by force if necessary. Although most countries, including the United States and the Philippines, do not recognise Taiwan as an independent state, the US is against the use of force to assert control of the island.

The Philippines, located just 142km away from Taiwan, has expressed concerns about tensions in the Taiwan Strait.

Philippines Marcos doesn’t endorse Taiwan independence, seeks to avoid conflict

According to defence analyst Joshua Bernard Espena, Manila has been signalling to Beijing that its actions are reflective of its national interests in the face of China’s efforts to “consolidate its presence” in the South China Sea as well as the Taiwan Strait.

“To be embroiled in a conflict is to say that we are either reactive or we are thinking of how we are going to benefit in a time of crisis such as this one because we cannot stop or predict Beijing’s timeline,” he said.

“We need to take into account that the Philippines has no choice but to take proactive stances,” added Espena, who is Vice-President at the International Development and Security Cooperation think tank in Manila.

The Asean challenge

China has overlapping claims with several Southeast Asian nations in the South China Sea.

The Southeast Asian claimants, despite some internal differences, reject Beijing’s “nine-dash line” claim to around 90 per cent of the waterway.

Aristyo Rizka Darmawan, a lecturer in international law at the University of Indonesia, said Asean might not be well-equipped to respond immediately to any spontaneous escalations involving its members.

“What is more important for Asean now is to prevent such a scenario from happening,” he said. “In doing so, it is important for Asean to allow diplomacy through all channels of communications, such as the negotiation of the COC.”

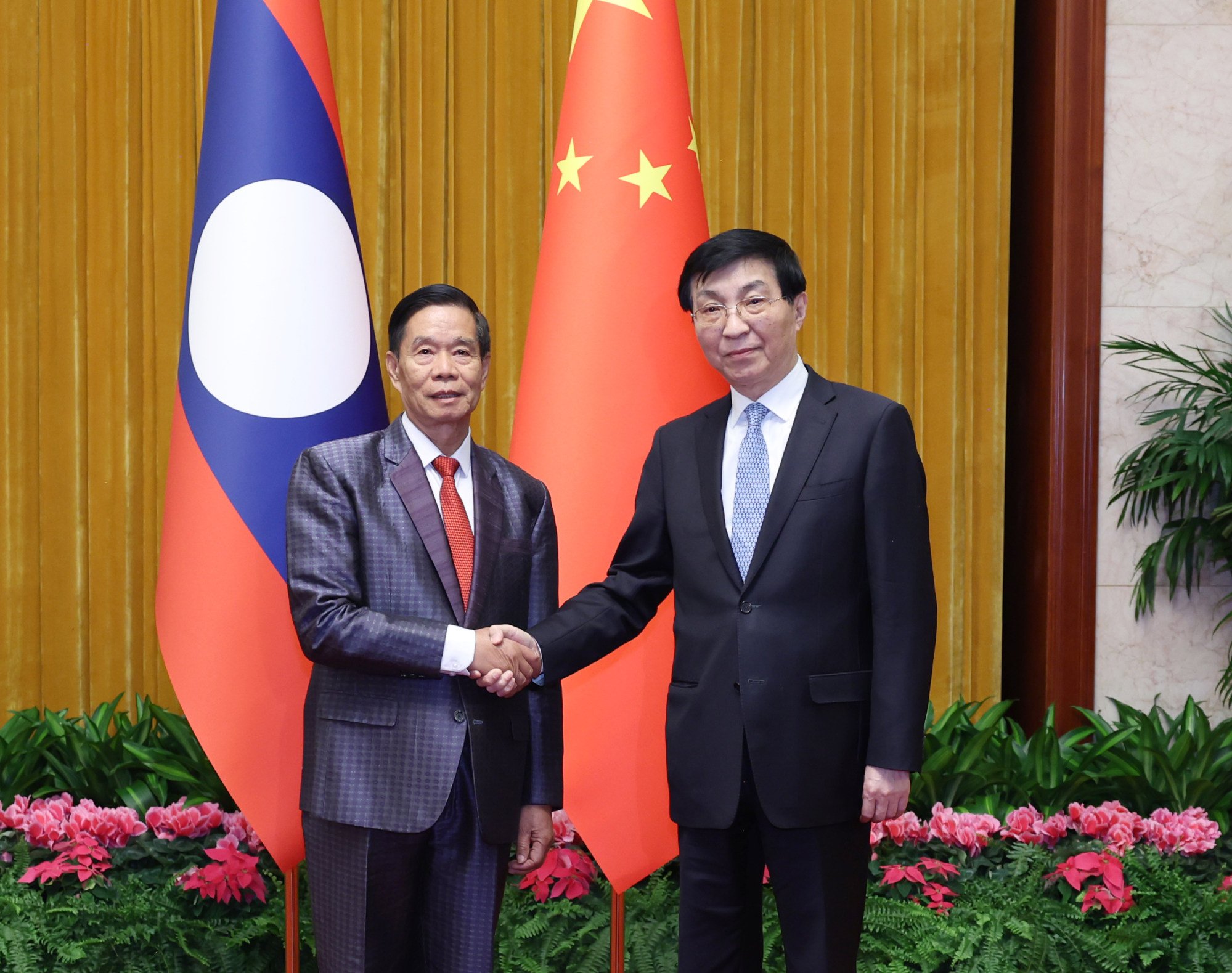

Laos-China ties

And what could make matters a little more complex this year is the new chair of Asean, the Beijing-friendly Laos.

Communist-run, landlocked and poor, Laos has hooked its economic fortunes to China, which has in turn extended billions of dollars in loans to Vientiane for infrastructure projects, including railways, roads, and dams.

As such, questions have been raised about Laos’ political willingness and capacity to push back against Beijing in the case of heightened conflict, and if Beijing were to further its assertiveness in the South China Sea.

As Asean’s rotating chair, Laos is expected to help lower tensions in the region, not adding fuel to the fire by siding with a particular party

According to Collin Koh, a senior fellow at Singapore’s S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, the mainstream perception of Laos’ alignment with China over its economic dependence may be a “linear argument that amplifies the prognosis that Laos would do China’s bidding”.

Koh highlights Cambodia as a similar case, being labelled as “China’s Trojan horse within Asean”. This label arose when the group failed to issue a joint statement during Cambodia’s chairmanship in 2012 due to the dispute over the Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea.

Controversy erupted when member states accused Cambodia of blocking mention of the dispute over its alliance with China. That was the last time Asean could not reach an agreement and produce a joint declaration.

“I think since then, Cambodia is still trying to mollify and even remove that label as the spoiler within the group, and I think that has had profound lessons for all Asean member states.

“I don’t think Laos is willing to be seen as trying to wreck up the Asean process,” he added. “Even if Laos has very important stakes with China, it is important to note that the other member countries will influence Laos if not for their own national interest, but also for regional interest.”

Vietnam, for example, has been intensifying its interactions with both Laos and Cambodia in recent years, Koh said, in part to ensure that its neighbours are not becoming too close to China.

“Vietnam may be trying to keep an eye on what Laos is up to when setting its agenda for Asean during its chairmanship, because it seems Vietnam has been focused on keeping Asean as central as possible,” Koh added.

Asean may have an additional safeguard in place through the “troika method” introduced by the outgoing chair, Jakarta. This means Laos will collaborate closely with Indonesia and the next chair, Malaysia, in addressing regional crises, particularly the issue of Myanmar.

“It is in all Asean countries’ interest to avoid any kind of military conflict in the region,” said Zhiqun Zhu, a professor of international relations at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania.

“As Asean’s rotating chair, Laos is expected to help lower tensions in the region, not adding fuel to the fire by siding with a particular party.”