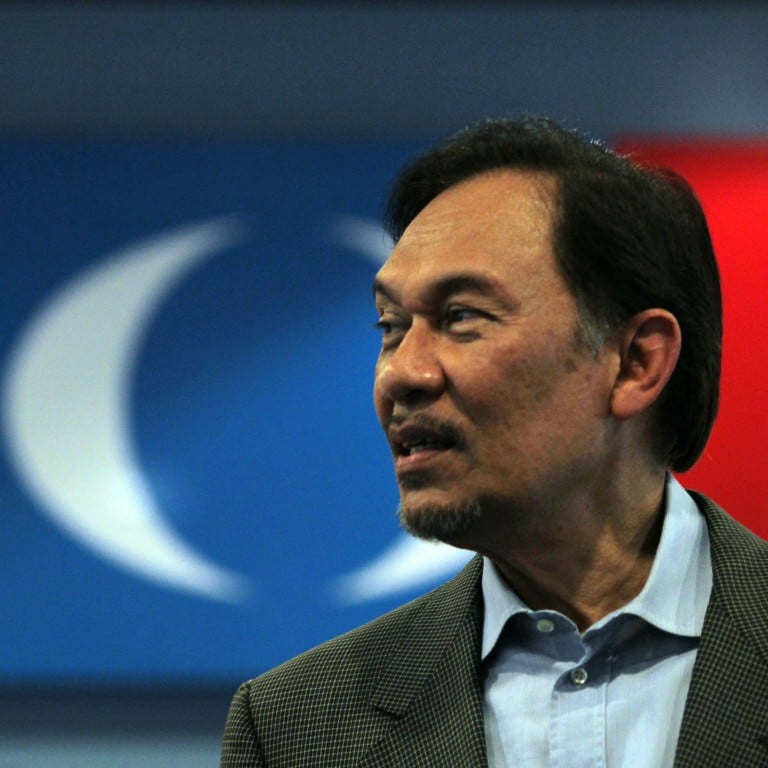

At 25, Malaysia’s PKR seems on the up but is Anwar Ibrahim’s star power holding it back?

- Without a formidable and charismatic replacement, Anwar’s People’s Justice Party remains firmly wedded to its president’s political fortunes

- ‘The party is paralysed’, one PKR insider told This Week in Asia. Others insist its reform agenda is on track, and say succession talks aren’t needed

But as PKR marks the 25th anniversary of its formation this year – and Anwar turns 77 – the question of who will succeed him as leader of the 1-million-strong party remains unanswered.

Malaysia’s ‘Casio king’ charged as corruption probe nets another Mahathir ally

Analysts say the party is at a crucial juncture in charting the future direction of Reformasi, the reform movement started by Anwar months before PKR was founded.

In 1999, Anwar spoke about the need to reform a nation in which corruption had stalled its economic progress. Many Malaysians find it hard to envision PKR’s future without Anwar at the helm, with reform hopes still pinned to his name.

“I think PKR cannot fully detach itself from Anwar until the party finds a truly formidable and charismatic replacement,” said Syaza Farhana Mohamad Shukri, head of the political science department at the International Islamic University of Malaysia.

To the PKR’s staunchest supporters, the party’s commitment to reforms is intact.

“We have not given up on our idealism,” said Sim Tze Tzin, a senior MP from the party.

On Sunday, PKR will mark its 25th anniversary at a convention in Kuala Lumpur, where its leaders are expected to present their vision for the future. It was founded on April 4, 1999 and was originally called Parti Keadilan Nasional, or the National Justice Party.

PKR had a clear mission at that time: free Anwar and lead the fight against the widely perceived endemic corruption and crony capitalism under the Barisan Nasional coalition government led by Mahathir.

While in jail, Anwar burnished his image as a man obsessed with cleaning up Malaysian politics and serving the people, rather than the country’s tycoons and their political allies.

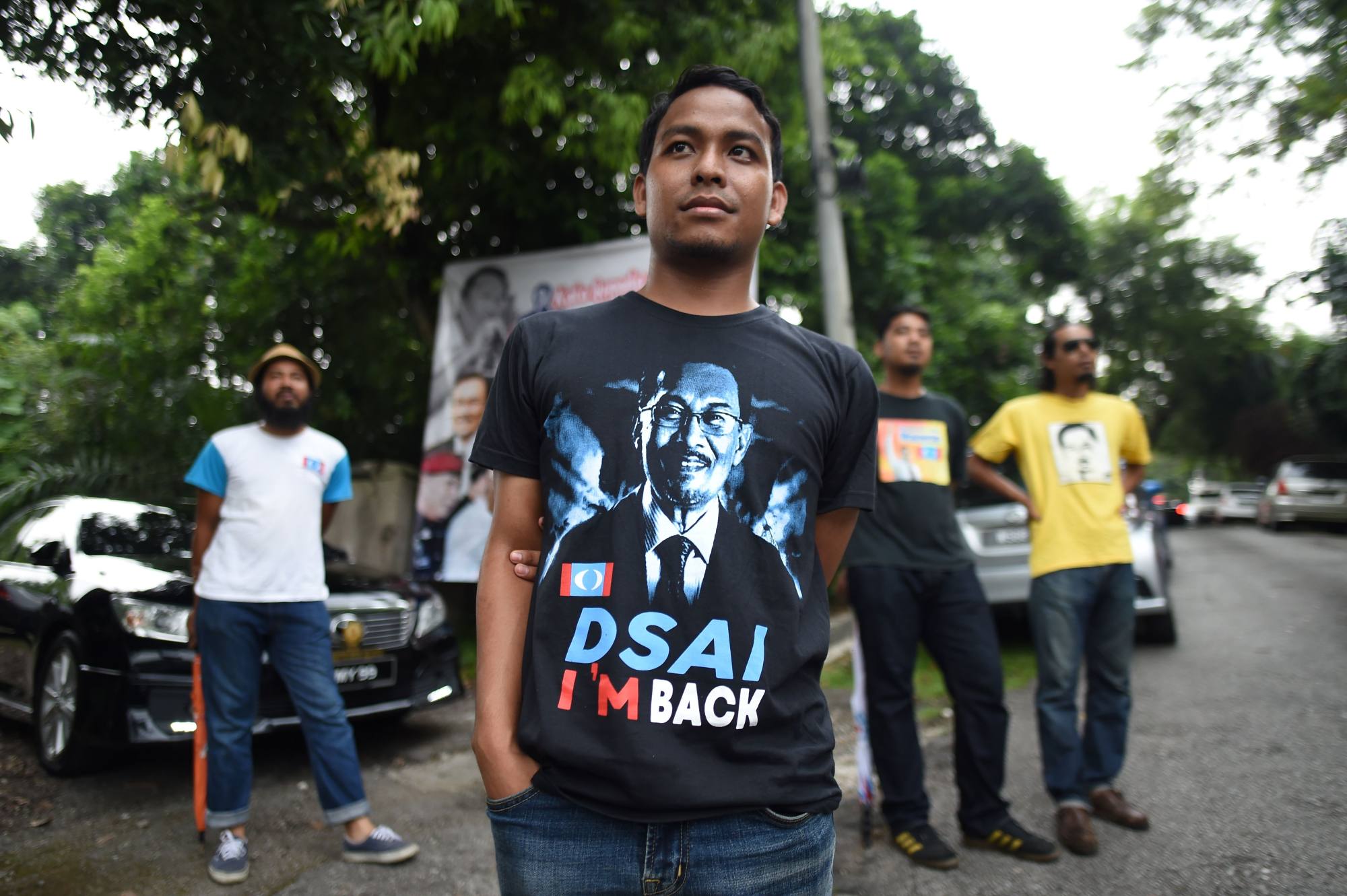

Anwar’s Reformasi movement grew into a potent force that spurred a political awakening among Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese and Indian minorities. They had for decades grumbled over growing racial inequality and the alleged plunder of the country’s riches by those in power.

“PKR is committed to multiracialism, multiculturalism, justice for all … we firmly believe this is the way forward for the country,” PKR’s Sim said.

The movement came to a head in 2007 when opposition parties and civil society groups launched street protests that rocked Kuala Lumpur. Up to 100,000 people turned out in the streets for the first rally by the Bersih coalition to demand free and fair elections in October of that year, as protesters clashed with riot police.

The following month, about 30,000 Malaysian Indians launched a rally to protest against years of discrimination and marginalisation.

The Barisan Nasional government felt the fallout from the rallies in the 2008 general election, when it lost its parliamentary supermajority for the first time in nearly four decades.

At every turn, PKR’s image has been firmly wedded to Anwar’s fortunes.

Party insiders say he employs a divide-and-rule strategy to manage PKR – carried over from his days as a leader in Umno, when he often pitted his subordinates against each other to undercut any potential challenger.

That approach was on full display in PKR’s internal polls in 2018, which saw a bitter fight between then-deputy president Azmin Ali and Rafizi Ramli for the No 2 spot.

Rafizi’s campaign was widely seen as having Anwar’s backing following a falling-out between the president and Azmin – the man credited by party veterans with growing PKR while its leader was behind bars.

The months-long campaign split party members, many of whom were also angered by numerous discrepancies in an online-voting system implemented that year, including allegations of thousands of dubious voters and data failures.

“The party is paralysed,” said one PKR insider, who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the matter. “Party staff don’t know if they should carry out instructions from one side because the other camp may suddenly tell them to do something else.”

Are there good leaders? Yes … but the problem is they are often overshadowed by Anwar

Far from having a lack of talent, PKR’s problem lies in Anwar’s dominance of the party to the extent that it has stymied room for the next generation of leaders to emerge, political analyst Bridget Welsh said.

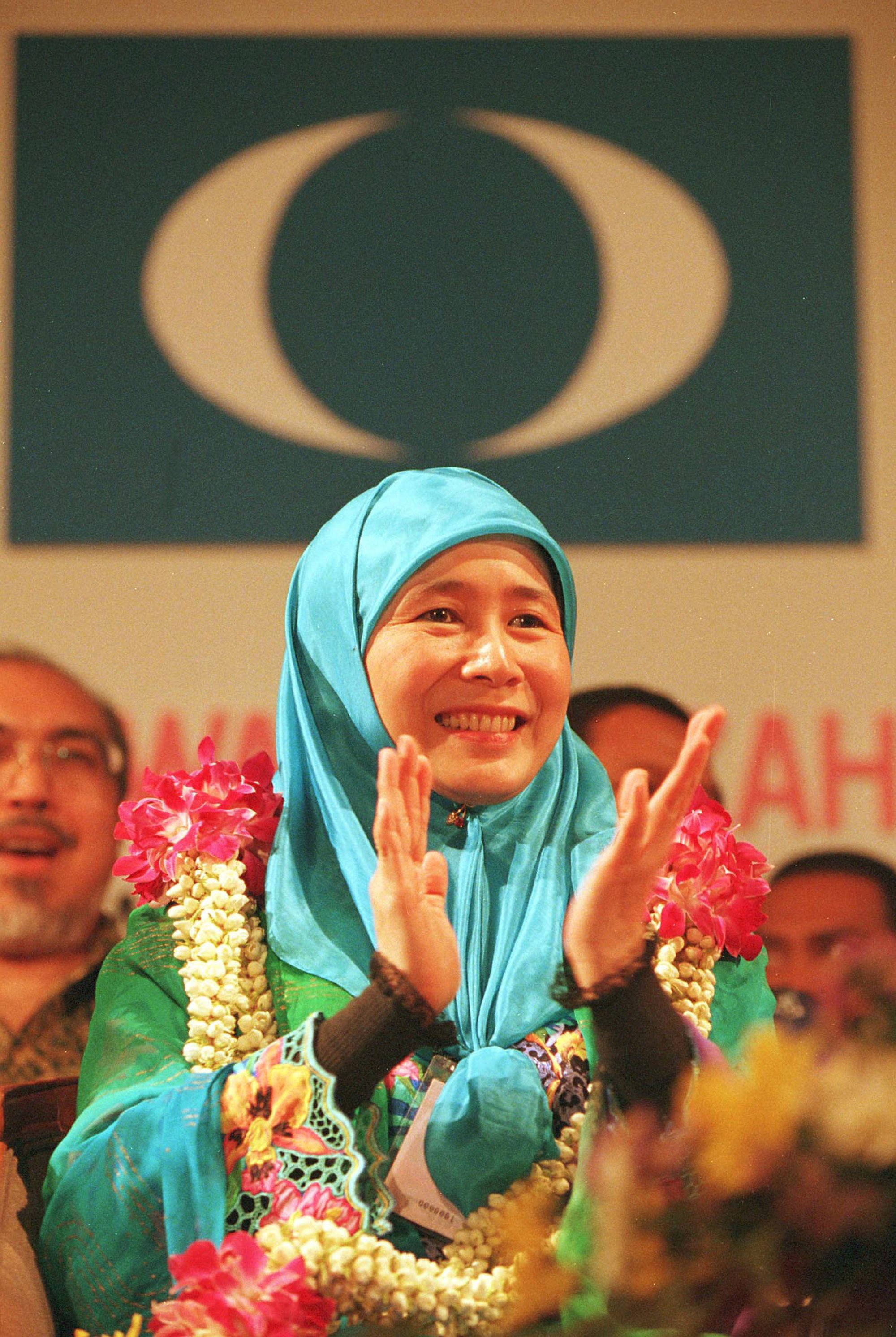

“Are there good leaders? Yes … but the problem is they are often overshadowed by Anwar,” said Welsh, who named Rafizi, vice-president Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad and Anwar’s eldest daughter Nurul Izzah as potential future leaders.

The party also faces an identity crisis as critics accuse Anwar and PKR of not living up to their reform pledges.

“[PKR’s] multiethnic identity has not translated to practice or policy. This points to how the party will be identified … it talks about a multiracial polity but no multiracial government,” Welsh said.

‘Nothing’s been done’: has Malaysia’s Anwar lost momentum to make reforms?

“It’s about convincing people from different backgrounds that the multiracialism and reform agenda can work, and will work,” Adam said.

Until then, some in the party feel it is too soon to be talking about succession, as Anwar is just one and a half years into his term as prime minister after spending the past two decades waiting for his chance to get into office.

“We have a very large group of younger leaders ready to take over the party and build on the vision set by Anwar,” Sim said.

“But right now it is too early to talk about succession. [Malaysia] set the [world] record of a 93-year-old becoming PM, so why can’t Anwar continue?” he said, referring to Mahathir’s age when he started his second stint as prime minister in 2018.