Journey to the past: why overseas Chinese are finally embracing their roots

Chinese immigrants once viewed the past as a black box – sealed shut to blend in abroad. But as new generations come of age, many are turning to genealogical services to search for identities that are fading with time

While he was growing up in the northern suburbs of Melbourne, Dennis Yeung was unaware of the differences between himself and the other boys. Sure, he was known as “Ching”, but even here he may have caught a break. One white classmate was known as “Buddha” because he was fat. Another kid was “Fungus” owing to wad of peach fuzz on his face.

Now, 68, the jovial retired mechanical engineer recalls that it wasn’t until he started shaving that the difference between he and the majority of Australians hit home. “You stand there in front of the mirror and lather up every morning, day in and day out, and eventually it hits you,” Yeung says. “This face in the mirror looking back at you is a bit alien.”

As China lurches forward, its 50 million strong diaspora, scattered to the far corners of the world during far less prosperous times, are increasingly looking backwards to the land of their forebears in a search for their roots.

In generations past, overseas Chinese traditionally viewed the past as a black box – sealed shut by nervous parents eager for family members to keep their heads down in a foreign world that is often majority white.

“You have to adapt or die,” says Raymond Chong, 62, of Sugar Land, Texas, recalling his childhood.

But as new generations come of age, many are now looking for clues to an identity that is fading with time.

Genealogical services offering help in tracing family trees are becoming increasingly popular, fuelled perhaps by the rise of reality television shows that document the ancestry of celebrities.

Why Australia’s cure for Chinese influence is worse than the disease

A civil engineer by profession, Chong grew up without learning Chinese and with little sense of the historical contribution that ethnic Chinese made to US history from the gold rush in California and building railways. “History was white washed. There was discrimination and hatred of anyone who wasn’t white. I didn’t know anything of my own identity.”

Chong says that changed 15 years ago, when a close friend with a mental illness took his own life owing to the trauma he suffered while deployed with the US military in Vietnam. Chong says his friend’s death underscored how toxic the past can be when it’s not addressed. Yeung’s journey started with the realisation that his four grandchildren – of mixed white and Asian background – were experiencing some of the same taunts that he had as a child.

“We’re supposed to have multiculturalism but the situation hasn’t improved,” Yeung says.

And while Yeung and his wife are healthy, he felt a special obligation as the eldest male to link his two younger brothers and their family with the extended clan in China. “After I go, a lot would be lost and it would just be harder,” he says of the genealogical search.

“This is about placing an anchor point down so that anyone who is interested in the family tree can research on their own.”

Trouble is there are few ways to put down that marker. Searching for long-lost family through the rubble of China’s turbulent past, including revolution, war, flood and famine, requires the cooperation of local governments – particularly in the south, which was the origin of many emigres. But few overseas Chinese speak Chinese, making it hard to access information online.

Both men hired My China Roots, a “bespoke” genealogical service, with about a dozen full-time staff and interns dotted around the country, according to the company’s founder, Huihan Lie.

My China Roots opened in 2012. What Lie has noticed since then is that clients know more than they think.

Of the 85 per cent of Chinese who emigrated to the United States through the west coast, for example, before the second world war, 85 per cent came from four counties in Guangdong in the country’s south, Lie says. Of the Chinese who settled in Jamaica and then moved north into Miami and the eastern United States, most come from an area with a radius of no more than 20km in modern day Shenzhen.

A young Chinese Indonesian straddles modernity and tradition

“Immigration was managed through networks, you didn’t do it alone,” Lie says.

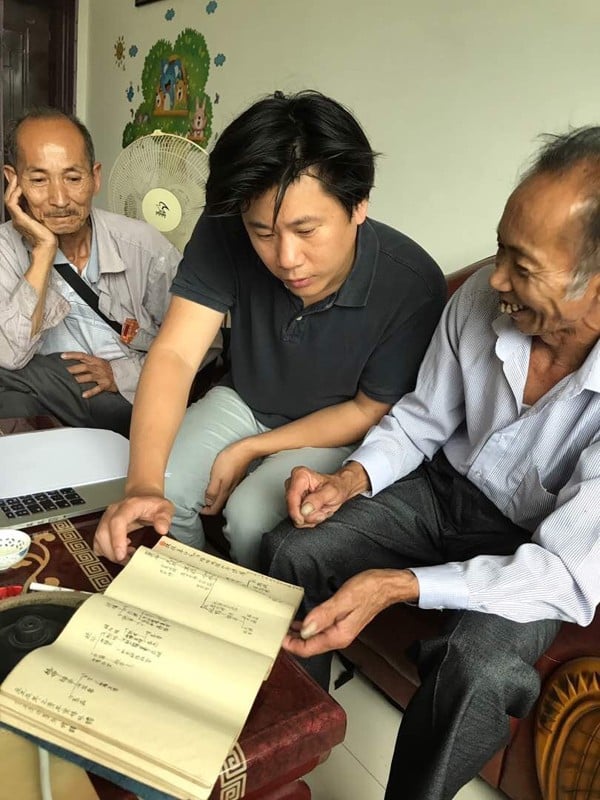

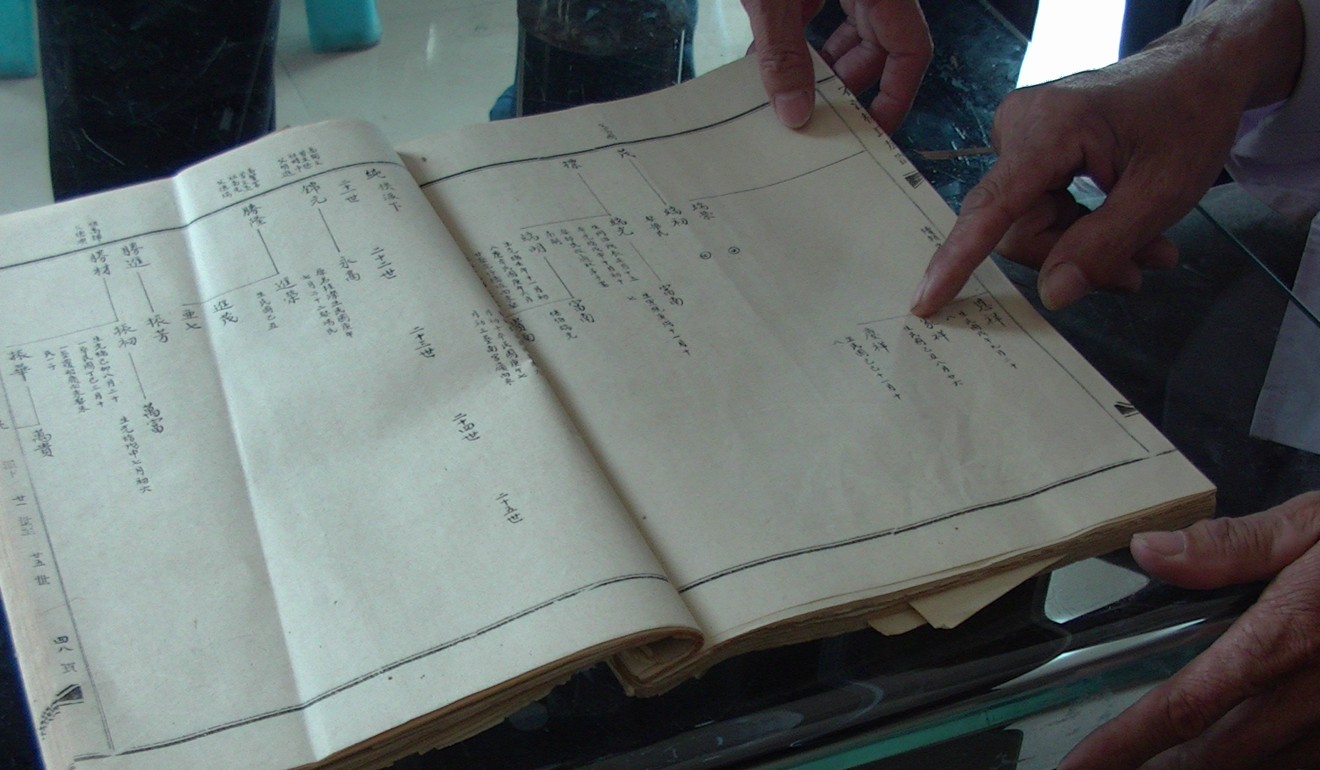

Yeung eventually tracked down his family in southern China and made a trip there last spring. Lie’s researchers had found the family registry, known as a zupu, in a small village more than four hours drive south of Guangzhou. Yeung says that seeing his father’s and grandfather’s name in the registry was a electrifying. He had found the home of his ancestors. “I got more than I bargained for,” Yeung says. “It was very emotional.”

Chong is making a documentary of his family’s odyssey that links to the California gold rush of 1849, the construction of the more treacherous links of the transcontinental railroad in the US and Chinese gang wars in San Francisco and other US cities. My China Roots is helping fill in the gaps of that project. “My family’s history is rich and it is the history of America. I didn’t know any of this before 2003,” Chong said.

Interest in genealogical services is gaining traction. Last year, Ancestry.com, which is privately owned, was expected to ring up revenues of at least US$850 million. The US documentary series Who Do You Think You Are, which has traced the family trees of celebrities including author J.K. Rowling and Bryan Cranston from Breaking Bad, has already run nine seasons.

Lie says that while My China Roots sales were little more than US$65,000 in 2016, they probably doubled last year. The company had 17 clients at this point in March 2017. Currently he has 35 customers paying thousands for projects that may take anywhere from 45 days to six months to complete. Born in the Netherlands, Lie’s ancestry stems from Indonesia and China. He grew curious about his own family tree when relatives drew a blank on the Chinese side of the family.

My China Roots has secured funding to start an online genealogy database specialising in Chinese ancestry.

Sending researchers into the field to find family records is expensive and not easily scalable. The database will kindle more interest from a wider market that may not be able to shell out a few thousand dollars to track down forebears.

“My passion is making people curious about their own stories,” Lie says.

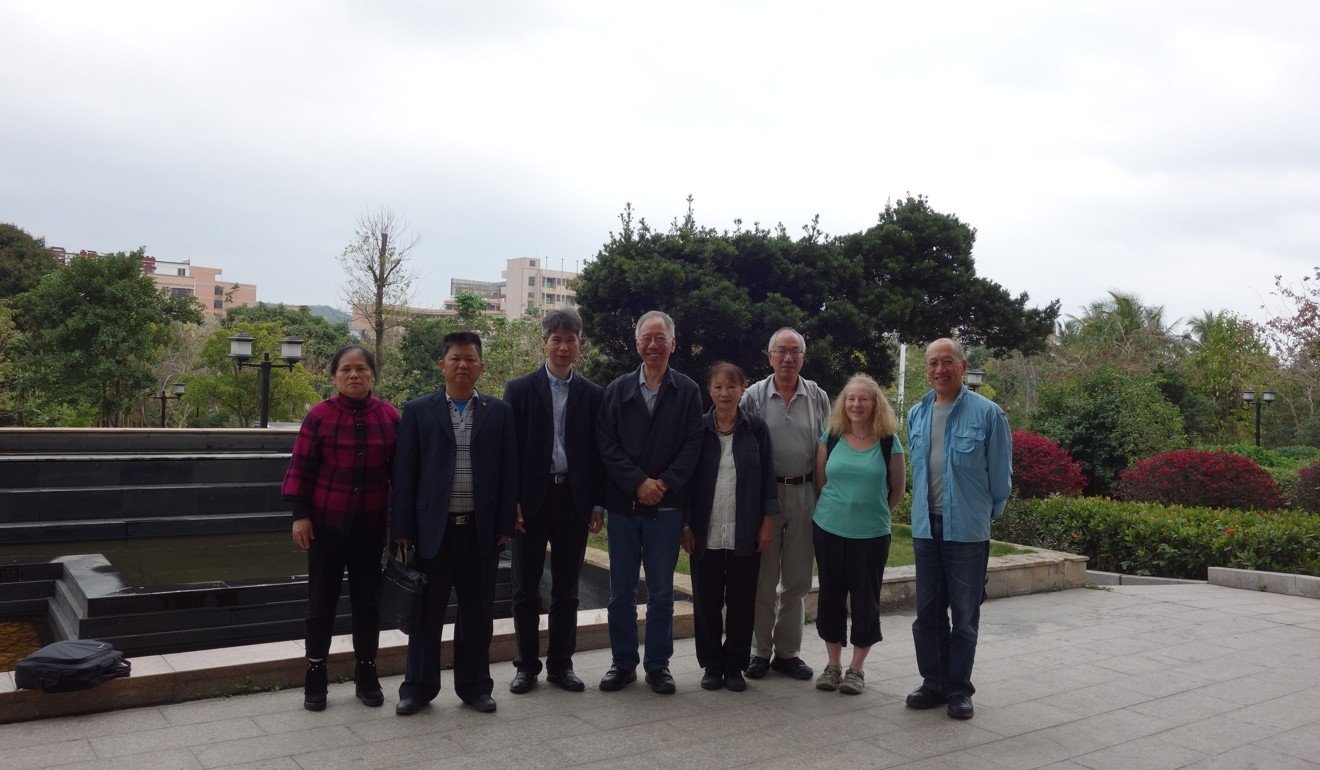

Both Yeung and Chong say the experience has opened their eyes to a wider world. Chong makes yearly pilgrimages to his ancestral village of Long Gong Li to the west of Macau to pay his respects to the stony graves of forefathers reaching back to the time of the Yellow Emperor, circa 2600BC.

Lie says that far from polarising people into ethnic camps, his clients report a sense of belonging and empathy after making the journey back to their ancestral village.

“No one has come back and said I feel more Chinese now and less, say, American or Australian,” Lie says. “At the end of the day we are all people with stories.” ■