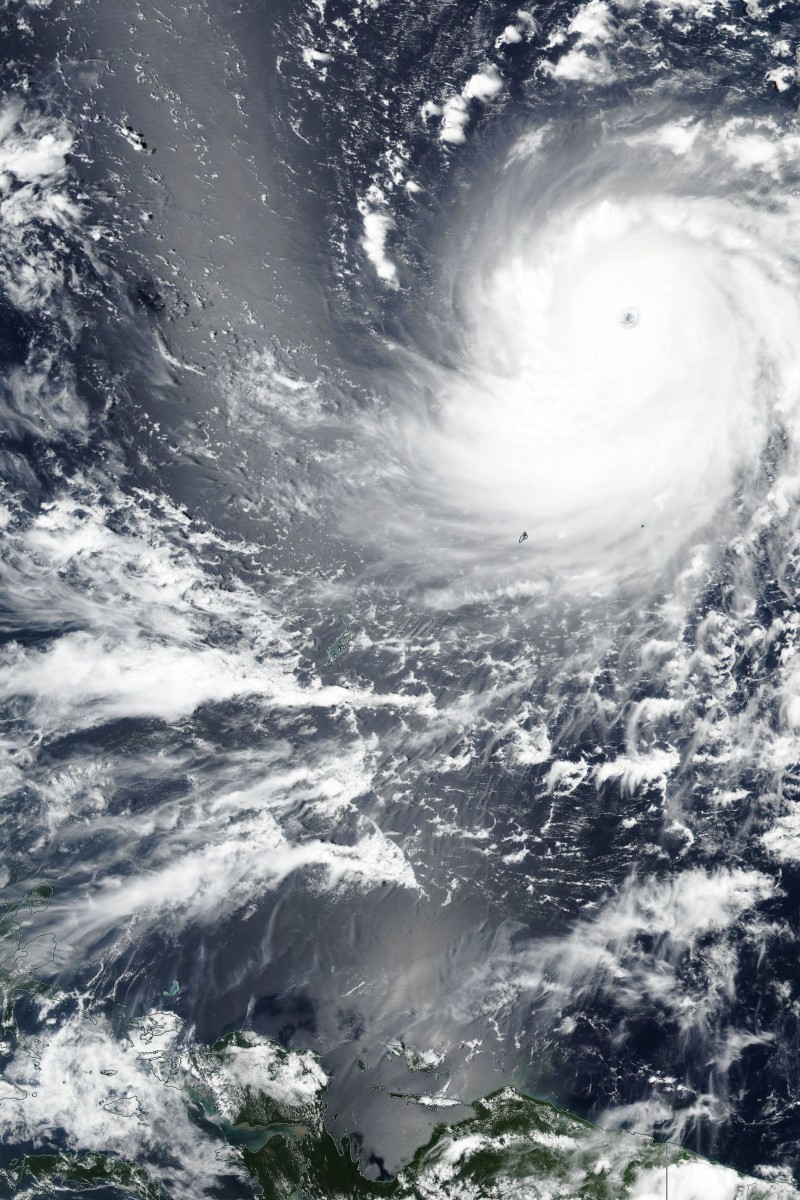

A Nasa satellite photo shows Super Typhoon Mangkhut approaching the Philippines on September 11. Its name is the Thai word for a fruit.

A Nasa satellite photo shows Super Typhoon Mangkhut approaching the Philippines on September 11. Its name is the Thai word for a fruit. As Tropical Storm Barijat moved closer to the city on Wednesday evening the Hong Kong Observatory issued the No 3 typhoon signal indicating strong winds. Meanwhile Taiwan braces for Super Typhoon Mangkhut, one of the strongest Pacific Ocean storms this year.

That storm is on track to hit Hong Kong on Sunday night.

Apart from the havoc such storms wreak, the other notable thing about them is the names they are given.

Super Typhoon Mangkhut approaches HK as Observatory warns of rough seas and flooding

Tropical cyclones are named by storm warning centres to make forecasters’ communications with the general public as easy as possible to understand.

It is less confusing to say “Cyclone Peter” than to remember the storm’s number or its longitude and latitude. It is also easier to use names when you have more than one storm to track.

Storm names are assigned in order from predetermined lists depending on which region of the globe they originate in.

The use of names for storms began with hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean, where tropical storms whose sustained wind speed reached 39 miles per hour (73 km/h) were assigned names.

Now, in addition to the storm forecasting centre for the Atlantic Ocean, those for the Eastern, Central, Western and Southern Pacific regions, the Australian region, and the Indian Ocean use this naming method.

Initially, storms and cyclones were named after the saint of the day from the Catholic liturgical calendar. These days, the year's first tropical storm is given a name beginning with the letter “A”, the second with the letter “B” and so on through the alphabet. In even-numbered years, odd-numbered storms get men’s names and in odd-numbered years, odd-numbered storms get women’s names.

In the western Pacific Ocean the Japan Meteorological Agency’s typhoon centre assigns international names to tropical cyclones on behalf of the World Meteorological Agency. It selects 35 names from an international list of 140 names supplied by 14 countries and regions.

The names of storms that cause widespread damage and death are usually retired. These names are replaced with new ones.

In the Pacific Ocean regions, each country contributes names for storms. Those from Hong Kong appear pretty lame, and haven’t exactly struck fear into those who hear them.

Find out how Hong Kong's weather shattered numerous records in 2017

Ma-on means horse saddle, and is also the name of a peak in the city; Lingling is a common pet name for young girls; Kai-tak is named after the city’s former airport, which closed in 1998; possibly the worst name of all is Choi-wan, which means colourful cloud but is also the name of a public housing estate in the city.

They pale in comparison to the colourful and fierce names put forward by China, such as Yutu, which stands for the Jade Hare, or the hare which lives on the moon. In Chinese legend, Chang’e, wife of Yi (a tribal chief in ancient China), stole her husband's elixir of immortality, and fled to the moon together with the hare. They are said to be still living there in a palace.

Other Chinese cyclones names are just as good. Wukong means King of the Monkeys; Haishen stands for the God of the Sea; Dianmu is for the Mother of Lightning; and Fengshen, the God of Wind.

As for the names of this week’s approaching storms, Barijat is a term from the Marshall Islands – a chain of volcanic islands and coral atolls in the central Pacific Ocean, between Hawaii and the Philippines – which means “coastal areas impacted by waves/winds”, while Mangkhut is Thai and is the name of a fruit. Another Typhoon Mangkhut made landfall in Vietnam in 2013, killing at least three people.

All of these sound more impressive than a storm that shares its name with a Hong Kong housing estate.