Advertisement

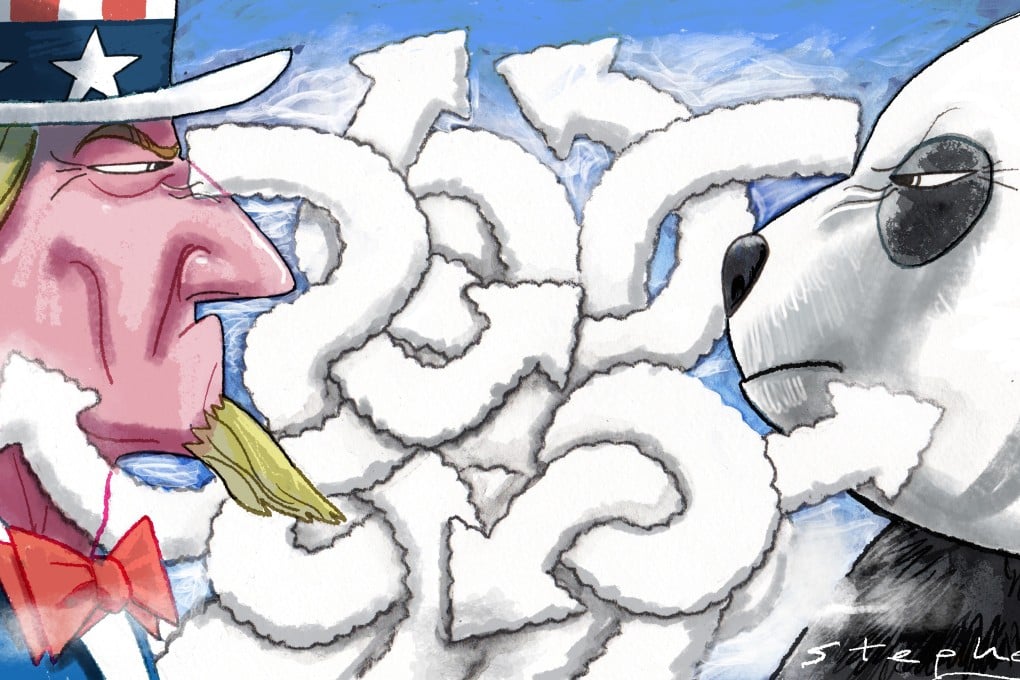

Opinion | Fog of strategic mistrust is stopping the US and China from seeing eye to eye

- The rivals blame each other for changing the Asia-Pacific security order and upsetting the status quo, and disagree over the true aim of US sanctions and path to peace in Taiwan

- For peace to endure, they must focus on clearing the causes of their strategic mistrust

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

6

Unable to articulate a strategy on China in the league of coherent grand strategies such as “containtment”, “detente”, or his predecessors’ “responsible stakeholder” and “pivot to Asia”, US President Joe Biden’s China strategy is a bewildering utility cupboard – the US sometimes competes with China, sometimes cooperates with it, and at other times confronts it.

Conveniently, Chinese policymakers have organised Biden’s China strategy into what they call the “five noes”: the US seeks no cold war, no conflict with China, no change to the Chinese system, no containment of China with allies, and no support for Taiwan’s independence.

But it is unhelpful to define US-China relations by its negative attributes, and the genial political posture reflected in the “five noes” is undermined by the consistently hawkish and restrictive actions taken against China.

Indeed, Chinese President Xi Jinping does not believe America’s stated position. During the “two sessions” earlier this month, he told China’s top legislators that “Western countries, led by the United States, have implemented all-round containment, encirclement and suppression of China”.

Strategic misunderstanding has long afflicted relations between the US and China. Neither has managed to assure the other of the validity of its world view and the sincerity of its intentions.

Four strategic questions are central to the state of US-China relations today. One, who is changing the status quo of Asia’s security order? The US believes it is China. It believes China has prematurely imposed “one country, one system” on Hong Kong, and created artificial islands and unfairly claimed large bodies of water in the South China Sea.

Advertisement