How did the Hong Kong film industry get so big – and why did it fall into decline?

Of the many national cinemas Hong Kong’s was once one of the most distinctive. Although it owes a large debt to its mainland heritage, Hong Kong cinema helped popularise entire genres of film such as kung fu and wuxia on top of creating specifically local genres like mo lei tau comedies and heroic bloodshed action films. During its heyday from the mid-80s to the mid-90s Hong Kong films dominated the box office in East Asia and enjoyed a cult reputation in the West.

Despite the city’s size, it exported more films than every other country in the world except the United States. Local stars Jackie Chan and John Woo became bona fide Hollywood celebrities and the likes of Chow Yun-fat and Jet Li also had the chance to shine Stateside. According to film historian David Bordwell, at its peak Hong Kong produced “arguably the world’s most energetic, imaginative popular cinema”.

How did Hong Kong cinema manage to reach those dizzying heights and why has it declined into near irrelevance in more recent years?

The first film of fiction made in Hong Kong is generally accepted to be Chuang Tsi Tests His Wife, made in 1913. Although by 1939 local studios were making more than 100 films per year, in both Cantonese and Mandarin, the then British colony was second to Shanghai in cinematic importance.

Legendary Hong Kong director Johnnie To’s 5 most underrated films

That changed after the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, which mired the Chinese industry in bureaucracy and saw many filmmakers flee south.

Hong Kong was ideally positioned after the communist victory to take advantage of the situation. The city had an established studio system and as a British colony it could access Western film stock and equipment. The government believed in the rule of law and exercised a light touch when it came to regulation of the film industry – until 1988 there were not even any levels of film classification in the territory.

Local filmmakers took advantage of all of this and prospered. With Chinese communities spread throughout Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia – not to mention Taiwan – Hong Kong movies had eager audiences across Asia. In the 60s, studios mimicked the popular Japanese jidaigeki samurai films, producing their own Chinese equivalent such as the hugely popular Come Drink With Me (1966) and The One-Armed Swordsman (1967).

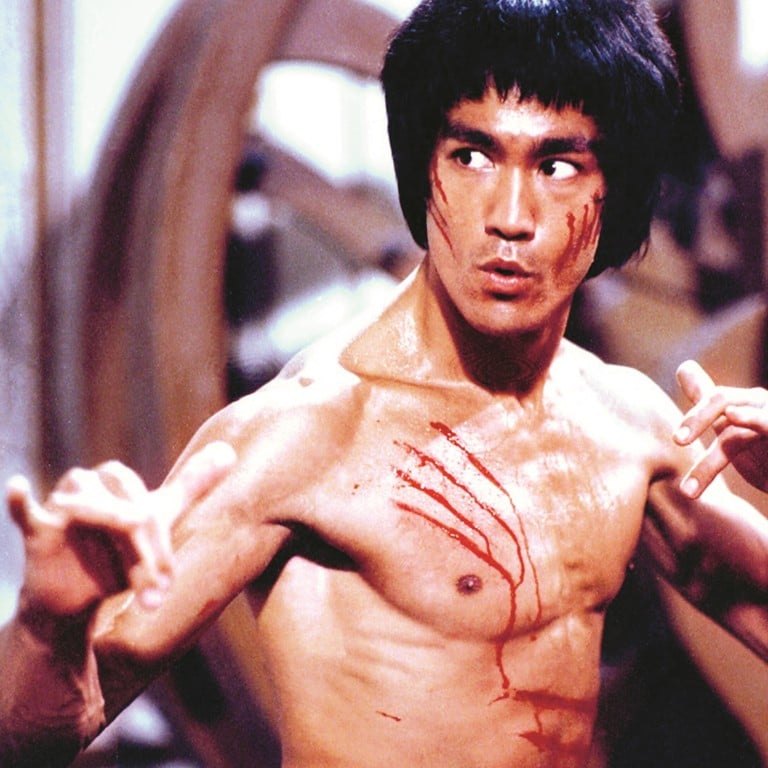

Then came Bruce Lee. An international icon to this day, Lee’s break out role was in The Big Boss (1971), which set box office records across Asia. Lee’s follow-up, Fists of Fury (1972), broke those same records and his final film, Enter the Dragon (1973), released posthumously, made him an international star even after his untimely death.

Almost simultaneously, Shaw Brother’s Five Fingers of Death (1972) arrived in America the same year as Enter the Dragon. Hugely popular, together these films helped bring Hong Kong films out of Chinatown cinemas in places like New York, San Francisco and Vancouver and nearer the mainstream. Exotic yet accessible, their impact was so big that local filmmakers produced kung fu movies specifically for international audiences that would not even play in Hong Kong.

Why did Ray Yeung direct the new LGBT movie Suk Suk?

Against this backdrop of lightning-fast kicks and lethal punches, a quieter revolution was occurring. The big budget swordplay films that were tremendously popular were almost exclusively filmed in Mandarin – the Cantonese-speaking community and market being much smaller. It may seem strange now but in 1972 Hong Kong produced no Cantonese movies at all.

This abruptly changed in 1973 when the comedy The House of 72 Tenants was released, topping the box office charts and setting new records in Hong Kong. Michael Hui’s subsequent Cantonese comedies confirmed the trend – his film Games Gamblers Play surpassed 72 Tenants’ new box office record the very next year. The establishment of the Hong Kong International Film Festival in 1977 increased foreign access to local cinema and fostered further consideration of the city’s cinematic heritage.

The above set the scene for the Hong Kong New Wave – whose films, by the likes of Ann Hui and Tsui Hark, demonstrated there was more to local cinema than just chopsocky fisticuffs – and Hong Kong cinema’s golden age.

This period, generally accepted as spanning from 1986 to 1993, saw Hong Kong films continue to dominate the local and regional market. Much of the new blood that now entered the film industry had studied abroad and they brought with them an appreciation of Western standards of filmmaking that further elevated Hong Kong films above regional competitors. The result was, according to director Wong Jing, “an Eastern spirit in a Western package”.

7 things you didn’t know about Leslie Cheung

East Asia could not get enough of this hybrid product and Hong Kong producers did their utmost to appeal to them. Leading actors were recruited from across the region – the likes of Michelle Yeoh (Malaysia), Brigitte Lin (Taiwan) and Oshima Yukari (Japan). Poking fun at this opportunism, Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express features the Taiwan-born Japanese pop star Takeshi Kaneshiro as a Hong Kong policeman speaking heavily accented Cantonese who happened to learn Japanese during his education in Taiwan.

Different cuts were made to appeal to different markets. Taiwanese and Korean distributors wanted more action, so fight scenes were extended for their versions of films. Given the sensitivities of censors in Malaysia and Singapore, criminal elements of certain films were downplayed – extra scenes were shot for the Young and Dangerous franchise explaining that the “heroic” triad protagonists were actually undercover police.

Unfortunately, the situation could not last. The turning point was 1993 when Jurassic Park stomped into view and topped the Hong Kong box office. The same year, Taiwan, long the most lucrative overseas market, saw the introduction of cable and satellite television, enticing viewers to stay at home rather than visit the cinema.

Since the 1980s the international market had come to represent more than half of Hollywood’s theatrical revenues. With its huge population and increasingly prosperous consumers, East Asia was a prime target for further expansion. The success of Jurassic Park was followed by The Fugitive (1993), Speed (1994) and True Lies (1994). Simultaneously, American studios began investing in cinemas in Japan and other major markets, helping them to push their product more aggressively. Hong Kong itself was not immune to this thirst for US blockbusters, which continued to gobble up more and more of the box office.

The arrival of modern multiplex cinemas in Hong Kong in the 90s was an issue too. Although they offered patrons state-of-the-art sound, seating and projection, they came at the expense of the old cinema halls that could seat more than 1,000 customers. This meant that even if the number of cinemas was increasing, the number of seats – and tickets available to be sold – was actually going down.

Who was Tina Leung, the Hong Kong movie star who regretted a nude scene?

Another huge structural issue was building. Just as the number of seats was declining so were costs starting to spike. Much of this was due to star names demanding ever higher salaries – in the early 90s Jet Li’s million-dollar salary could reportedly eat up a third of a production’s budget, slashing margins. As Hong Kong’s property prices rose inexorably higher, cinema chains invariably passed the burden of higher rents onto their customers via higher ticket prices, providing an incentive for them to seek entertainment elsewhere.

Hong Kong studios’ problems were compounded by endemic piracy. Already a bother in the 80s, this ailment spread dramatically in the 90s thanks to the development of VCDs (Video Compact Disc). So adept were Hong Kong’s pirates that Manfred Wong, producer of the Young and Dangerous franchise, was able to buy a pirated copy of Young and Dangerous 4 on the day of its premier in 1997.

During the peak years of production in the early 90s, per capita Hong Kong had the most active film industry on the planet. It’s a stat often used to trumpet the former strength of the industry. On paper it seems impressive, but actually, this was a source of great weakness since many of the hundreds of films produced were substandard. With a huge number of investors seeking a quick buck in this buoyant market – including triad gangs, a dark side to the boom years – the result was overproduction of poor quality movies.

This, coupled with filmmakers jumping from one trend to another in search of the next big thing, resulted in audience fatigue. Suddenly, Hong Kong’s fabled ability to churn out movies in rapid fire succession went from virtue to vice.

5 of Louis Koo’s best movies – from Throw Down to Paradox

These were also the boom years for the newly classified Category III films. These typically sleazy productions came with such appealing names as Raped by an Angel (1993), Girls Unbutton (1994) and A Chinese Torture Chamber Story (1994). Often, their plots were equally unappealing. Pretty Woman (1991) – not a remake of the Julia Roberts/Richard Gere hit – had a storyline centred around a woman being raped and murdered and then replaced with a hostess lookalike by her killer.

Although certain Category III films were popular and a few met with critical acclaim – Anthony Wong Chau-sang won Best Actor at the Hong Kong Film Awards for The Untold Story (1993) and Shu Qi Best Supporting Actress for Viva Erotica (1996) – the vast majority were a turn-off for audiences. With a great deal of local productions proving to be unsatisfying – various estimates state that at their peak between 25 and 50 per cent of new Hong Kong films were Category III – cinema-goers increasingly turned towards Hollywood.

The damage was plain to see. In 1988 Hong Kong cinemas sold 65 million tickets. By 1993 that had declined to 45 million and three years later the total was down to 22 million. In the early 90s the city produced some 400 films a year – more than Japan with its vast economy and population – but by 1997 production had declined by more than half. In that, the year of the handover, total box office grosses of imports surpassed those of local ones for the first time in decades. It was a symbolic shift that shattered the confidence of the Hong Kong film industry.

Then came the Asian financial crisis, dealing a further knock to an already reeling industry. What few Hong Kong productions were still being bought in the region were being purchased in heavily devalued currencies.

Tony Leung Ka-fai’s 5 best films

Stretching in to the future, a final problem was forming. Hong Kong cinema had long been bolstered by international stars like Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Leslie Cheung who appealed to audiences across the world. Unfortunately, Hong Kong never resolved the question of who was to come after. As the film industry slid into decline, filmmakers continued to rely on established stars who were considered reliable earners.

But now Chow Yun-fat is 64, Andy Lau is 58, and even Louis Koo, the youngest of Hong Kong cinema’s current big names, is set to hit 50 this year. In the last 20 years no new stars have emerged to replace the old guard. No matter how popular these actors are at home, to the rest of the world it seems like the same old stars in the same old movies. Contrasted with the unceasing conveyor belt of new Korean celebrities in recent years, it is easy to see why other countries stopped paying to watch Hong Kong movies.

The film industry never recovered from this succession of blows – blows that kept coming with the likes of Sars and mainland China’s determination to push its own cinema. There is an irony to this as some of the most accomplished Hong Kong films were made after the industry’s peak, such as In the Mood for Love (2000) and Infernal Affairs (2002), not to mention the most mature works of established directors like Ann Hui and Johnnie To. But to borrow the title of Derek Yee’s 1993 hit, c’est la vie, mon cheri.

Want more stories like this? Sign up here. Follow STYLE on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Twitter .

The Hong Kong film industry once produced stars like Bruce Lee, Chow Yun-fat and Wong Kar-wai: how did it get so big, and why did it fall?